JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

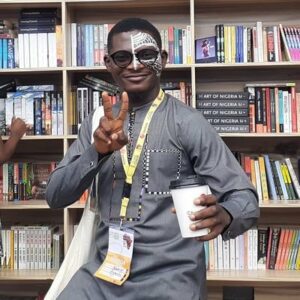

I interviewed prolific Nigerian poet and editor Adedayo Agarau who was a finalist in the 2021 Sillerman Prize.

Adedayo has several published chapbooks, including For Boys Who Went, The Arrival of Rain and Origin of Names (selected for the New Generation African Poet – African Poetry Book Fund – 2020) and his individual poems are in demand with magazines such as World Literature Today, Anomaly, Frontier, Iowa Review and Boulevard.

As an advocate for new African writing, Adedayo edits Agbowó: an African magazine of literature and art, and the New International Voices Series at Icefloe-Press. He also edited the groundbreaking Memento: An Anthology of Contemporary Nigerian Poetry.

Leslie: Tell us about your own creativity – in particular how you came to be a human nutritionist, a documentary photographer, and a poet. What’s the common creative ground between these different disciplines and how do they differ?

Adedayo: Creative writing is informed by everything the eyes have seen, everything the body has learned about. Human Nutrition taught me the science of existence, photography showed me the way light enters the body and poetry documents these things; everything I know and continue to learn. When I started writing, I didnt know that I’ll someday be writing about the concept of existence & the science of it. Everything needs everything.

Leslie: How has the country, district, family and society you grew up in shaped who you are, both as a citizen and writer?

Adedayo: The writer is first a citizen. And continues to be, even after the country abandons it. The hornets’ nest with being a writer is that we carry everything, not knowing which to shed. Having stated here that the citizen and writer are the same, all of the influences you mentioned above are all the same journey.

I bloomed out of my family—one in which we missed one another too often,—I grew into a society of loss. My friends were kidnapped. Some died. North of my country is in a constant war inside itself. There is a political plumage fueling the fires they put in people’s houses.

So all of these influences point towards absence and loss and that the body ashes, literally and figuratively, it ashes. What is the difference between the lost and the dead?

Leslie: What are the main characteristics of the poetic worlds I’d encounter reading your chapbooks For Boys Who Went & The Arrival of Rain & The Origin of Names?

Leslie: What are the main characteristics of the poetic worlds I’d encounter reading your chapbooks For Boys Who Went & The Arrival of Rain & The Origin of Names?

Adedayo: The body, as I believe, is a mortal custodian of memory; so the poetics of the body, its miracle & disaster, saturate my work. The poetics of childhood and memory. The poetics of matter; what fills space, what makes it, what catches it, and how does space matter, are questions I ask in relation to what is lost, who is lost. For Boys Who Went, my juvenile chapbook, prepares me for what memories bring, by first identifying what grief is. In The Arrival of Rain, I accept the years and years of longing, witness loss, speak in the language of doors. In the Origin of Name, I enquire about the science of naming in Yorubaland, the concept of godhoods and origins, how language shifts from one tongue to the other. All of these books speak with one another. They are layers and layers of memory and knowledge.

Leslie: How do poems come to you? What’s the process from first spark to finished piece? What’s rational and what’s intuitive in your approach?

Adedayo: More times than often, poems come to me whole. When it comes, like silence or the absence of it, I write the work. The spark is, on several occasions, enough. I also, sometimes, have to rework how light enters the poem, or how it departs from it. My process is very flexible, really.

Leslie: Who are the narrators in your poems? Looked at both technically and emotionally, why do you choose those particular voices?

Adedayo: The narrator in my poems is the boy/the son/the man. These mirror me.

Leslie: What’s the relationship between autobiographical truth and made-up experience in your writing?

Adedayo: The characters. They are alive everywhere. Fictional poetry is often a product of near-experience. Or could be forgotten dreams. When a poet is unable to identify what’s true and untrue in their own writing, they have successfully blurred the thin line between their story & their other stories.

Leslie: You edit publications featuring African poets. What are the shared characteristics of these writers? What marks them out as a new poetic movement?

Adedayo: Samuel Adeyemi discusses grief like love; soft, beautiful, tender & unable to hurt. Ernest Ogunyemi’s poetry about loss fills an entire house, in the way that he does it, his poems fill the space that is left of what is lost with imagery that hangs pictures everywhere. Jeremy Karn writes about Liberia and the war—the graffiti on the tarred roads, the head split in front of a bullet-ridden house. Ugochukwu Damian writes about desire like a cross.

Everything these young talents discuss is also in conversation with the body, which can be a place, a destination, a body that is a part of a body. This is the generation that looks inward and writes from the inside out. The contemporary African poet is observant, careful and patient with their subject. They put everything to light, which can be subsequently interpreted as language, and see what is inside, what breathes or doesn’t, and what happens when it’s left in the dark. The African poet is a scientist as I mentioned earlier. Their poetry is a high precision metal scalpel, cutting [into the body], searching for where it aches.

Leslie: Why do you write?

Adedayo: The single work of the poet is to document. I am. That’s why I continue to write.

the boy’s body as an asylum party

& crossdressers have worn your mother’s kaba.

in this one, you are watching the morning

become fireflies growing out of ash clouds.

you think about dancing with the girls

but your body is tender spirit leaking into its grave

your father is in this poem as a wound in your leg

& he is why you cannot dance parties

you are shaping time into memory

you are sifting names away, calibrating chaos as your body pleads

you are asking your reflection

what it means to be rainbow washed clean in salt water

to be ocean & embers of flames

riding your body with fingers all at once

to be a body the metaphor of rain

the way it trickles and trickles

Adedayo Agarau

Next week I interview composer, baritone and conductor Clive Whitburn who has often performed at venues such as the Royal Albert and Festival Halls and the O2 Arena.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |