Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed aroace agender writer, artist and performer Arden Hunter who founded Cutbow Quarterly literary magazine. Arden writes erasure poetry, audio poetry, collage, found and digital visual poetry as well as straight, on-the-page poetry/fiction. Arden says about their work “… the theme tying everything together is an inexplicable and unconditional love of the ridiculous beast that is called ‘human’. “

Leslie: You say you’re an ‘aroace agender autistic writer, artist and performer’. You also used to refer to yourself as ‘Triple-A Battery’. Could you expand on what those phrases mean in terms of your work and how you experience the world, please? How does your neurodivergence manifest itself as a creative force?

Arden: I think it’s pretty common for writers and artists to look around at what other people are creating in order to get ideas and inspiration. Growing up, poetry seemed to mainly be about falling in love, lost love, the highs and lows of love… Artworks were explained to me in terms of how the artist related to the world, usually involving a tragic romantic affair, infidelity, or loss of a partner. As an aroace person I don’t relate to people in the same way; love and relationships are not a driving force in my life. I think that’s why for a long time I didn’t share my creative output, because I assumed no-one was going to connect with it. It was only when I discovered that there are so many people in the world who are just like me that I realised there was a place for my art as well.

The ‘triple-A battery’ thing was a defence mechanism – to call myself a ‘thing’ before anyone else could. I used to feel like I had to ‘come out’ to people over and over again. This week I’ll explain asexuality, next week I’ll try agender, eventually we’ll get around to neurodivergence… It can be exhausting, so I used to make it into a joke to get it all out at once. These days I think enough of my personality and identity shines through my work that it’s an easy jumping-off point for discussion.

As for being a creative force, my own brand of neurodivergence brings me new shiny hyperfixations every once in a while. I can suddenly become obsessed with a piece of media or a food or even just an idea: overnight, zero to one hundred. I can focus on that thing (sometimes to the exclusion of everything else) to the point where artwork and writing about that thing just pours out of me – an artistic info-dump, if you will. I have a very strong insatiable need to explain whatever it is to the rest of the world, but in a way that is uniquely ‘me’ at the same time.

Leslie: Why do you call your forthcoming collection ‘Stop Fidgeting’?

Arden: ‘Stop fidgeting’ was a common phrase in my childhood – not from family, but at school or in after-school clubs and other social gatherings. I am sensitive to textures, and as a youngster didn’t know how to channel that sensitivity into anything other than fidgeting. I think a lot of people will have heard the same phrase as being uncomfortable, especially in formal wear, seems to be a common childhood occurrence.

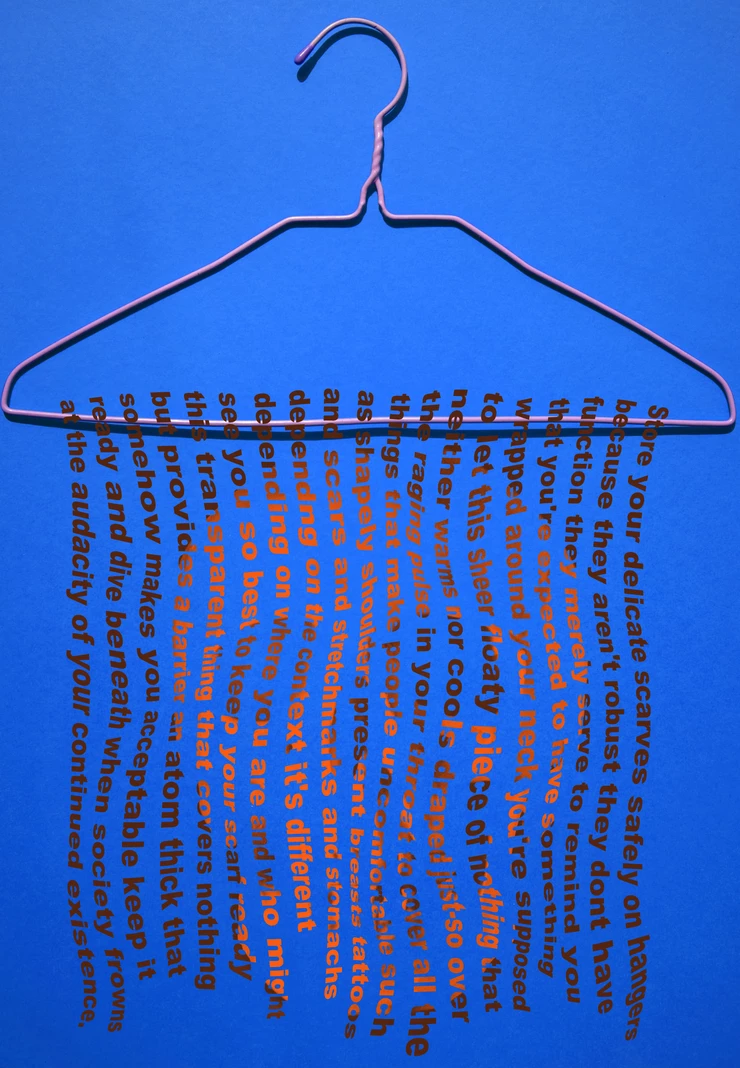

To me, the phrase says more than just, ‘be still’: the subtext is also, ‘accept your lot. Don’t complain. Comply.’ The collection explores the relationship between clothing and other day-to-day items and the concept of gender (something I did not understand at all when I was a kid) and how those societal gender norms are enforced through desired presentation. So, ‘stop fidgeting. Wear what we want you to wear. Be who we want you to be. Don’t ever step outside the box we put you in.’ It’s in many ways an angry collection, reacting to these arbitrary edicts.

Leslie: Could you describe how the poems ‘Camouflage’ and ‘Scarves’ from ‘Stop Fidgeting’ began, grew and developed, please?

Arden: I have a bit of a love/hate relationship with scarves. On the one hand they are very useful; I have lived in very conservative countries with hot climates, and throwing a big lightweight scarf over my head and upper body to cover up is very convenient. The few scarves I have are also made of very nice material so they don’t set off my skin. However, I still get annoyed at having to use them at all. The older I get, the more it seems I am ‘supposed’ to wear scarves – cover up the wrinkles in your neck, soften your edges, etc. and basically whenever I start feeling like I’m ‘supposed’ to do anything based on pointless societal expectations, it bothers me. ‘Scarves’ is very much an angry rant about that.

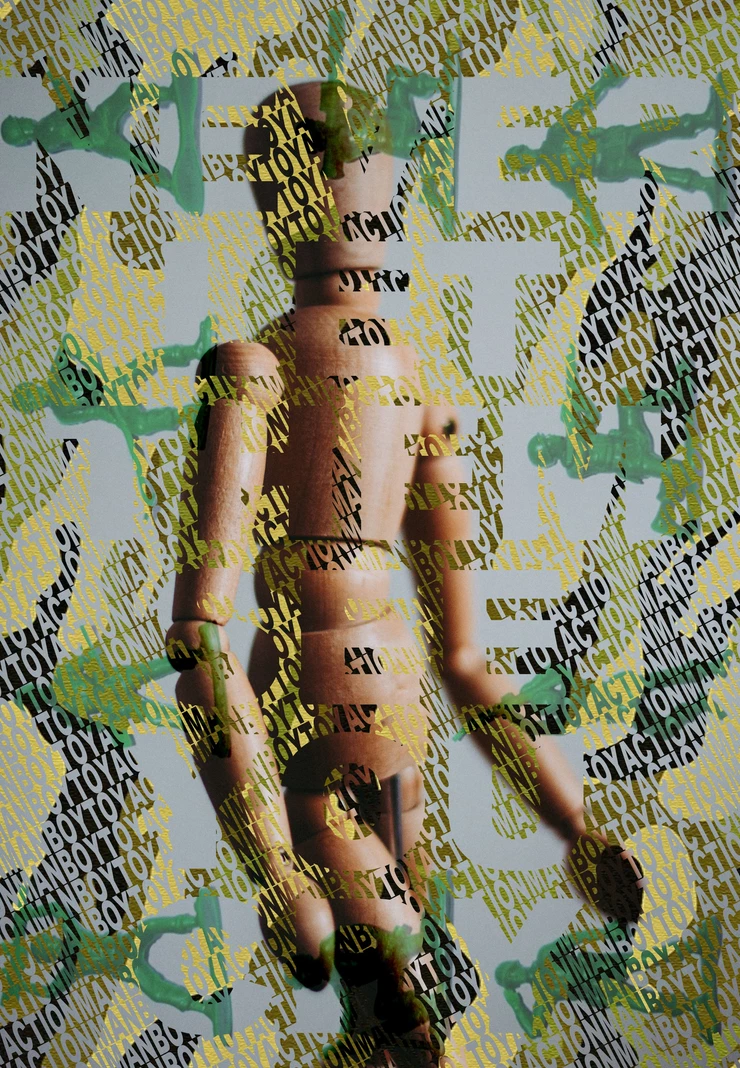

‘Camouflage’ came about because as the collection developed, I realised I wasn’t representing viewpoints other than my own. I wanted to explore all the ways that gendering items represses people, not just people who look like me. So I talked to my friends who present as ‘traditional males’ and asked them about their experiences, and those conversations informed ‘Camouflage’ and a few more pieces in the collection. The piece is about how men are traditionally expected to present strength and fitness, sex appeal and aggression, but still somehow blend in with the crowd. All the people I talked to said they wished they had been able to express their own personalities better through their presentation when they were younger.

Leslie: Can you give us examples from your work of the creations (other than Camouflage and Scarves) that carry the greatest personal urgency? Why are these pieces important to you?

Arden: ‘Ballet shoes’ was one of the first pieces I made for this collection. It shows a background of skin with curling pink ribbons on the side, and sentences criss-crossing the page. The words are the colour of purple bruises and you can see how they press into the skin and cause pain. I have clear memories from when I was young and went to ballet classes of having these torture devices called ballet shoes strapped to my feet and ankles. It was just accepted by everyone – the instructors, the other kids, family members – that this was going to leave you bruised and battered and in pain. I couldn’t understand why everyone accepted it, why no-one else was fidgeting like I was. I carried that bemusement with me and it had to get out onto the page.

Another piece that came very easily to me was ‘Cleavage’. I included a lot of different common phrases about breasts that are cat-called to young people, or whispered as chastisement. These phrases of course are contradictory – I myself have heard both ‘cover yourself up’ and ‘show us your tits’ on the same day. As a neurodivergent person this was particularly difficult to understand, particularly as again having these things said to you seemed to be accepted by society; you’re just supposed to put up with it. Well, I won’t. I don’t! I hope reading the words in this piece will help highlight just how ridiculous the whole thing is.

Leslie: How do you write/create visual art? Is it in snatches, repeatedly revised, inspired by real-life events, dream-like, slowly constructed or instinctive? How do you ensure that you remain creative and produce your best work?

Arden: It’s usually very intense and very fast. When the obsession comes over me, I’m not going to do anything else – talk to anyone, go out, I even forget to eat and use the bathroom. The pieces in this collection took around six hours each (average; some were an hour, some were twelve) and I made them every night and every weekend over a month until they were done. There was some editing needed afterwards (e.g. if I noticed an incorrect spelling), but usually when I think I’m finished with a piece after this intense flurry of activity, I don’t go back to it later. My creative process is fueled by a kind of furious passion; I have to ride the wave when it appears, because once it’s gone, it’s gone. The way I remain creative is to recognize this process and trust that there are more waves on their way in the future. If I try to make or write something when I’m not feeling it, it really goes nowhere.

Leslie: Why do you sometimes want the reader to feel confused? What’s unique about the writing/art you’re offering?

Arden: Much as I want to get my ideas across and create a shared understanding between me and the viewer, I don’t want it to be easy. When someone just tells you something, you might nod and smile and think you’ll go research it more later, but the odds are you’ll just go on with your life. However if someone hints at something and you’re interested to know more, you’ll go find out about it yourself out of curiosity, and that searching process, that learning process; it stays with you. I want people to have a moment of disorientation when they see/read my work, a moment of discovery. I want them to feel accomplished when they find the answer, and that answer is going to be different for everyone who views the work. I don’t just want them to understand, I want to co-create understanding.

You can find out more about Arden Hunter’s collection ‘Stop Fidgeting’ here.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |