Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed poet Katy Evans-Bush, whose career has spanned communications in the not-for-profit sector, single motherhood, poetry, critical essays, and ten years as a freelance (with clients like the Poetry School, Modern Poetry in Translation, and The Southbank Centre). Her blog Baroque in Hackney was shortlisted for the George Orwell Prize for political writing. Her first two poetry collections were published by Salt, Broken Cities, the second of her two pamphlets, was a winner in the Poetry Business competition in 2017. In 2015 Katy’s essay collection Forgive the Language was published by Penned in the Margins. She is working on a new collection called Like a Phone: From Lines by Kenneth Patchen. She lives in Kent and works as a freelance editor.

Leslie: How would you describe your role as a writer, where you draw your ideas from and what you do?

Katy: I think my role as a writer is to take part in the conversation that is literature. Writers are all in conversation with each other, throughout the ages, and with their readers. I think I had seen this by the time I was about five, and knew it was what I was for. And within that conversation, though I’ve always loved novels and stories, I think I had worked out that I was (at least also) a poet by the time I was about ten. I’ve always known I was a writer.

Poetry (as distinct from most prose forms) is about music, and pushing language’s boundaries, and creating effects that produce emotion in the reader — emotional revelations, reverberations, a sense of urgency. I agree with Shelley that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world — and of course it’s this unacknowledgement that keeps it (and us) real. It’s important to work under the radar. We’re truth-tellers, even if (and especially because) it’s our own partial and flawed truth. If you’re lucky you hit the main seam — the main beam — a few times in your life.

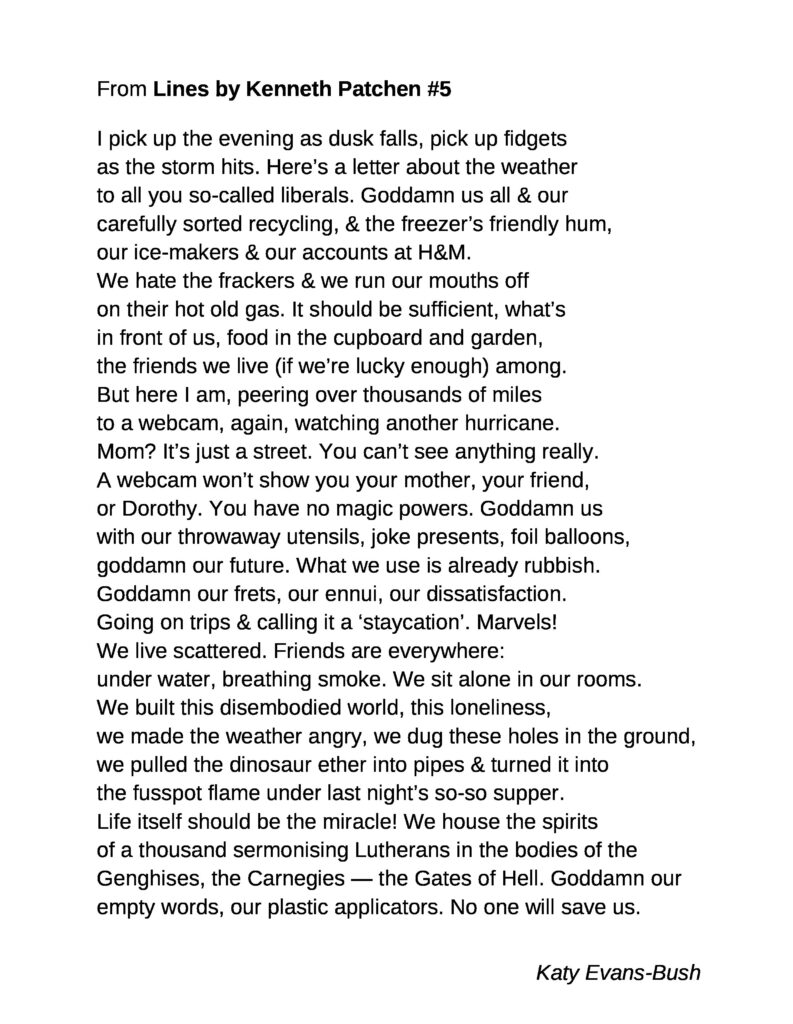

Leslie: Looking at From Lines by Kenneth Patchen #5, can you describe the full compositional process that went into this poem, please?

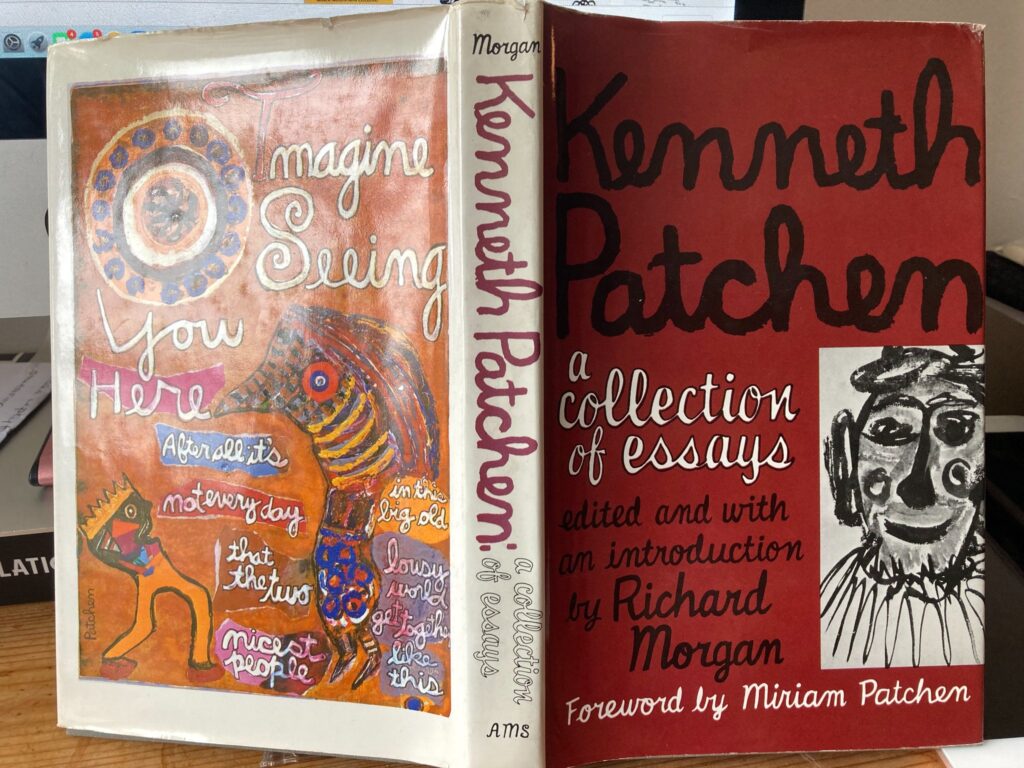

Katy: This poem is part of a full manuscript, numbered up to 50. The project was a sort of conversation, using phrases I had cut from my old broken teenage copy of Patchen’s Collected, and I started it to help me deal with my rage and despair about the state of the outside world. The process was the same for every poem: choose three or four or five phrases that resonate, very quickly, and use them as stepping stones for a poem. I worked quickly, not thinking very hard. Concentrating, but not really thinking. Like in a conversation. It was all based on whatever may have been on my mind in that moment, but it was all lightning-fast reflexes, like in a conversation, where you’re just saying things. I shape as I go. #5 is really a rant, I feel very strongly about all this. We’re helpless. The change needs to be cultural, it needs to be structural.

Leslie: How did you work on the other poems in the Kenneth Patchen sequence? What’s the key to making a poetry collection varied, vigorous, surprising and seamless/unified?

Katy: All the poems were written in the same way. I’d be feeling my way through images, echoes, using Patchen’s words – whatever I’d just chosen that was still on the table in front of me – as my guide, not to lose track, not to peter out into some pale, socially acceptable regret. I’d had a bad pandemic. I was on my own here, had had Covid very badly in 2020 (and am still struggling with the Long Covid), but I was writing this politely melancholy poetry full of medieval tropes (I live in a medieval market town, in essentially a Tudor garret) that got nowhere near what I was trying to get at – which was lost time, and the absence of the world. I was seething with rage and grief; these poems, which people liked well enough, actually felt fake and dishonest to me. Then the world came rushing back, and it was so upsetting I literally couldn’t even access it on my own. So I went for help, & Kenneth Patchen said yes. I started writing as the US and UK withdrew from Afghanistan.

This is the most unified poetry collection I’ve written, unless you count my now-out-of-print little pamphlet, Oscar & Henry (Rack Press, 2010). It’s a little like Louis MacNeice’s 1938 Autumn Journal, unified in time and mood, and the mood of dread is common to both. And, of course, this collection is unified by the presence of Kenneth Patchen through the whole thing. He was a very personal, very emotional, and very politically passionate poet, and a poet I loved very much in my teens. The subjects, as far as that goes, range from Afghanistan to Ukraine, from US anti-abortion laws to Burns night, from Rishi Sunak to the death of my Aunt Mary, but they all come from the same source. So: varied, yet unified. You can read another interview about how I wrote the sequence here.

Leslie: How would you like your ideal reader to approach poetry? Do you expect (and lay clues for) readers to decode the initial surface meaning of a poem? How is poetry distinguished from expertise in solving difficult and variable language games or an intensive course in esoteric music?

Katy: Oh, I’m not sure I know my ideal reader that well! My own poetry varies a lot I think, but mainly it’s about the interwovenness of language and the music it makes. I mean, using those two things to mine the emotional experience. I guess I’d love my ideal reader to have a keen ear for sound and rhythm, a sense of mood, and a sense of humour. Even the darkest of my poems — maybe especially the darkest ones — have jokes in them. Light and shade, light and shade…

I never think of ‘surface meaning’ or clues or anything like that. To me, the meaning is multifarious and all over everything. I love tone: you can change the meaning so much just by putting a word near other words, or using it in a particular context. There are so many connotations to even the most ordinary word: who uses this word? Is it an old word, a new one, slang? Because I was using lines by Patchen, I had access — this is the ‘phone’ aspect of the conversation, I guess — to a very demotic 1940s or 50s American register, which I come by honestly, having grown up in America and amid its colloquialisms. And can mix them with my London-inflected, internet-inflected, 21st-century English, to create my own idiolect.

The late Roddy Lumsden used to talk a lot about ‘idiolect’; he defined it as words not in the dictionary, but I think this was Roddy’s own marker for what the word actually means — ahem — in the dictionary: which is, the vocabulary that’s particular to the individual. Each of us has our own idiolect. When Roddy had a new collection coming out, he would publish on social media a list of the words that made up its idiolect. This grows out of, and makes up, the register, the tone, the mood, the social or cultural placing, of the book.

Beyond vocabulary, what about the overall feel of the poem, its lines? Are they smooth or choppy? What does the texture of it feel like? The most aggravating thing, to me, is reading poems that may be wonderful and even affecting, but keep going clunk – clunk – clunk. Inadvertent slips into rhyme or metre. Stresses in awkward places. Sounds that break the mood. You know, I’m with Don Paterson when he says that you can’t separate out the sound and its sense – that is, its meaning. And I think it was also Don who wrote that no poet is trying to write difficult work. The poem is an attempt to make something clear, in the clearest way possible, using all the tools at one’s disposal.

And Roddy, of course, was a crossword-writer and music nerd. I think a tendency to get into the tools of the trade is a help. There’s an anecdote WH Auden: a friend, I forget who, had sat in on one of his undergraduate classes, and asked him: ‘All the students are writing bad poetry. So how do you tell who the talented ones are?’ Auden replied, ‘They’re the ones who are in love with language’. But for a poem to work, to hover over the page and grab a reader by the hair, it can’t be just a clever word-puzzle. It needs to feel urgent, emotional, it needs to reach something inside the reader.

Next week I interview Frances Wilson, author of The Cross-Eyed Pianist, a leading classical music blog with c20,000 visitors per month.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |