Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

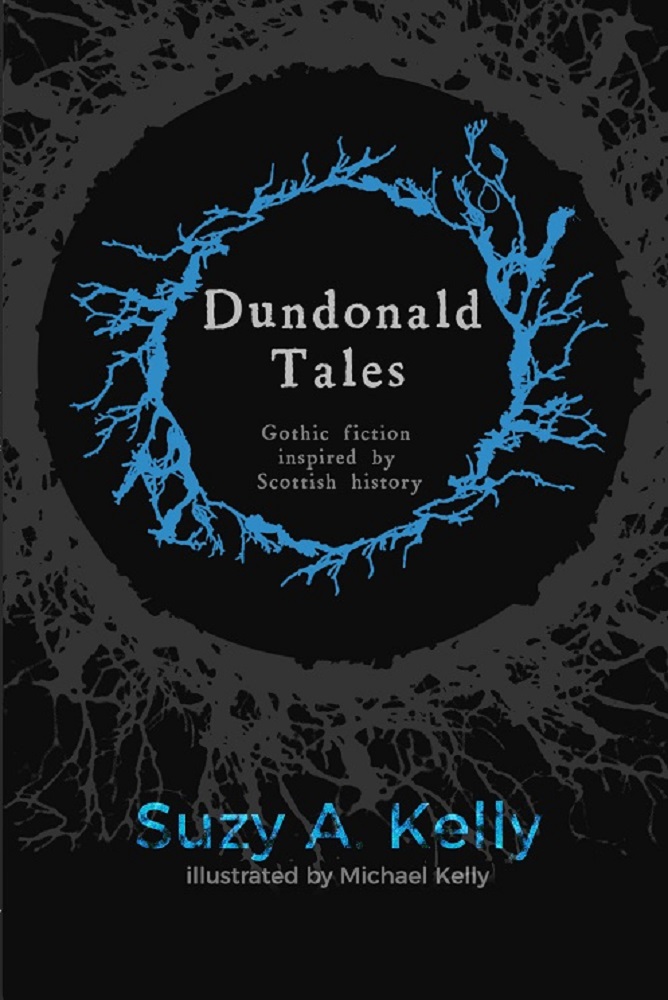

I interviewed neurospicy crime writer Suzy A Kelly who describes themselves as “a sweary, queer, disabled, non-binary, atheist, and intersectional feminist who was diagnosed with Combined ADHD in May 2022.”

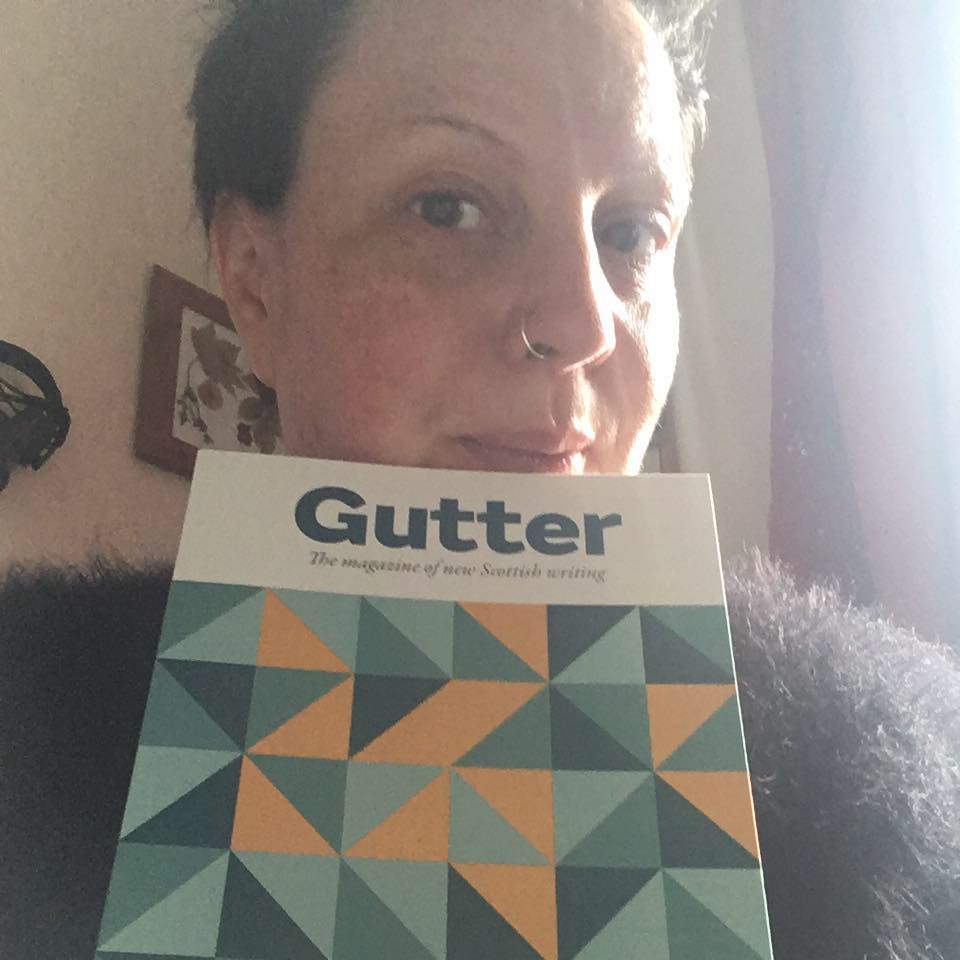

Suzy was commissioned by the National Library of Scotland to write about the Coronavirus pandemic and is currently working on a debut gothic historical crime thriller, Vile Deeds of the Amazing Crab Girl. Suzy’s short fiction, rooted in the dark folklore and languages of Scotland, is published in New Writing Scotland, Northwords Now, Gutter Magazine, and by the British Fantasy Society.

Leslie: How would you describe your voice as a writer? How does it relate to your personal voice?

Suzy: My writing voice is not a fixed entity. It changes in relation to the spirit of the character I’m inhabiting, but, in saying that, there’s always a gallows humour to my work. As a trauma survivor, I’m drawn to exploring the most difficult human experiences. Finding a resolution for a story usually involves breaking the tension with a mischievous sense of humour. I tend to squeeze into the minds of personalities who react to internal and external conflict in more extreme ways than I would ever dream of behaving in real life. For instance, I would never sanction the killing of a disabled friend like Mrs Beane does in ‘Them At Nummer Six’ (published in Gutter 22).

My writing voice is far less restrained. It amplifies things I struggle with in my personal life. For example, ‘A Most Peculiar Way’ (published by the National Library of Scotland’s Fresh Ink Initiative) was inspired by David Bowie’s music and developed out of the social isolation I experienced as a neurodivergent person during the Covid lockdown in 2020. My writing room (a desk space next to the washing machine) became a lunar module from which I examined life on earth via Zoom.

‘Waiting for Gordo’ (published in Gutter 19), grew out of heated family discussions around cremation. To resolve my phobia about being burned alive, I wrote the first draft from inside a bedroom cupboard in North Uist. This allowed me to channel the embodied experience of being trapped inside a coffin. By the time the final version was published, I had resolved my own fears and feelings towards end-of-life decisions. My writing is therefore a conscious exorcism of my personal anxieties. In her 1976 New York Times article, Why I Write, Joan Didion talks about not knowing what she feels about something until she starts writing and I identify with that approach. I’m unsure of what I think or what I want to say about a particular facet of human experience until I start writing about it with someone else’s mind. For instance, Mrs Beane’s journey from judging her neighbours harshly to developing compassion for them forced me to become more empathetic towards those who don’t share the same political opinions as myself. My personal voice then develops more confidence because of my writing voice.

Leslie: Tell us about how you compose your short stories. How do they begin, grow, and develop?

Suzy: My stories usually spark into being when I’m haunted by a new character. A voice will appear with a personality who has strong opinions or complaints or worries. I’ll feel them move in a way that’s peculiar to them but I can’t see them in my mind. I am hypophantasic, which means I don’t experience ‘mind pictures’ in the traditional way. Like, I completely fail the apple test. I cannot visualise an apple in my mind. However, I can imagine what it tastes like when I bite into it. I can imagine the crunch of my teeth tearing the skin. Failing that, I can buy one and meditate on its shape, its texture, its smell. There are ways for writers to get around these things.

It means I have to find another way of sensing my characters in my mind before I’m able to make them come to life on the page. With ‘Thrum’ (published in Sound of an Iceberg: New Writing Scotland 37), Hannah’s anger was the first thing that manifested itself to me. I was living in a terraced house at the time with neighbours who had wild toddlers running about screaming at all times of the day and night, as young children are wont to do. While I understood this on a personal level, I felt Hannah becoming more and more irate. She was pacing about in my head, shouting about the injustices of having noisy neighbours. I listened to her for a while, noting her style of speaking and her vocabulary, and then I explored the roots of her anger. Because it had to be about more than just the noise. Several mind maps later, it emerged that Hannah was bitter about losing a child. This alerted me to the fact that I was still struggling to resolve my own experiences of miscarriage. Hannah was doing this by weaponizing her anger and resentment on the world around her, as I had done myself in the early stages of my grief.

Society still has this expectation that early miscarriage is merely losing cells and that, because it’s not a fully-formed foetus, it means you should ‘get over it’ quickly. The inciting incident for Hannah then became this unresolved grief leeching into all facets of her life, especially her work life as her bosses and colleagues run out of patience with her.

Once I understood Hannah’s internal and external conflicts, I looked for outside sources to help me build a better picture of her, not as a flat ‘character’, but to create her as a real personality. So I turned to Pinterest to combat the effects of hypophantasia. Building a character board was the best way for me to visualise what Hannah looked like. It helped me externalise her and ground her in the real world since I could not picture her mentally. I looked for faces that intrigued me, for a physical build and a style of dressing that would reflect the high-pressure environment Hannah worked in. Keyword searches in Pinterest, Google image searches, photo archives, and museum exhibits are lifesavers for writers with hypophantasia (little mental imagery) and aphantasia (no mental imagery at all) because it overrides the parts of the brain that struggle with imagination.

So here was Hannah with her backstory, her internal conflicts, her inciting incident. Once I decided that she worked in a department store, I planned a research visit with my research assistant (my mum). I am diagnosed with ADHD and Myalgic Encephalitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which is a complex multi-system chronic illness with a huge social stigma. It causes extreme bone-crushing exhaustion after the smallest amounts of exercise. As well as chronic nerve, muscle and joint pain, it impacts on memory and other brain functions. In short, it’s an entire barrel of laughs. So, while on a research trip, my mum helps me navigate public spaces where I’m most likely to struggle with overwhelming sensory input and exhaustion. It’s also an excuse to drink copious amounts of tea and eat large quantities of cake for a few hours.

The research trip is the final ingredient for me to create the sensory experience of whatever story world I’m writing in. Also, my neurodivergence demands precision before I can commit to writing. Hence, for ‘Thrum’, mum and I traipsed up to Silverburn to hang out in a well-known department store. As I touched the different fabrics, I gauged Hannah’s reaction in my head, sensing if she squirmed or approved of the choices on offer. I even tried sampling perfumes to channel another facet of Hannah’s personality. It gave me another sensory prompt to use while writing as squirting the perfume on my wrist allowed me to drop into Hannah’s mindset much quicker.

We also just observed the ebb and flow of the store. What were the customers like? How did they browse the aisles? How did the sales people interact with each other, with the store, and with those who used it? Was there anything that annoyed them? Incidentally, there was plenty that annoyed Hannah, from the till receipt needing changed to the way customers knocked dresses off their hanger and left them lying on the shop floor.

The last item in my sensory arsenal is music. I use it to chart the emotional journey of a story. With Hannah, there were particular tracks that summarised her grief, her anger, and then her acceptance of losing her baby. With trauma, recovery is not a progressive linear experience. There’s a little step forward here, some regression there, and an easing and rising of tension in-between. Music can give writers a shortcut to accessing the mood and plot of whatever scene they’re writing.

Setting up a Spotify playlist helped me complete that missing mental imagery for ‘Thrum’. I started with a character playlist then expanded it into a plot-based one as the story progressed. The music can be of any genre. It could even be sound effects, like the ringing up of a till.

Sound also works as a memory prompt. I recreated the sound of the dressing room curtains being pushed back and that metal-on-metal crashing reminded me of hospital curtains sliding open. It brought back the full body horror of my own miscarriage ‘gloop’ landing on the ward floor, and the shock of knowing that this ‘mess’ was supposed to be my baby. The music helped me to access the real heart of the story. Channelling my experiences of child loss through sound brought all the strands of ‘Thrum’ together. Whenever I hear Anna Calvi’s voice now, it reminds me of poor Hannah and her, and by extension my own, traumatic miscarriage.

All my work begins with discovering a quirk of character. Mind maps, images, sounds, smells, and textures in the material world then help me develop the outline of the story. Memory and reflection are what help me locate the emotional journey of the character and this then informs the plot. I only discover the heart of the story once I sit down to edit it.

Leslie: What are the most important people/places/incidents from your life in Scotland that have gone into your writing? How have you adapted them to your stories?

Suzy: The people I’m most interested in writing about are those who struggle to navigate the world and society on their own terms. Neurodivergent people like myself, I guess. Since my diagnosis, I’ve found it easier to write alienated souls who are often written off as odd.

The Scottish influence comes from the places I’ve lived in across the UK and from the languages and cultures I’ve experienced. Part of my undergraduate degree was in Scottish cultural studies and I make sure to smuggle that influence into every story, usually from an outsider’s perspective. I try to balance mainland rural living with island-based life. So my stories are a mixture of Scots and Gaelic influences. With my shorter work, I prefer to write about these smaller places where there are more heightened consequences for messing up. Don’t be fooled into thinking that you’ll not be seen misbehaving on an empty Hebridean beach. There are always multiple witnesses. Whatever you’ve done or said will be roaring around the Co-op before you’ve even set foot off the sand. And I love that.

You also need to give back to the community to survive in these rural places. You need to share with your neighbours and become more understanding of each other’s foibles. You also need to have a well-developed sense of humour. Not having money, not being able to drive, living in fuel poverty, being disabled, being chronically ill, being anything other than white, heterosexual, and cis-gendered, and living alongside powerful natural forces makes this a more problematic environment to thrive in. And more interesting to write about. The anonymity of the modern city doesn’t appeal to me. My characters are always running foul of the unwritten social codes of rural life while searching for self-worth and belonging, as I am too. Until I was diagnosed as neurodivergent, I believed I didn’t fit in anywhere on Earth, which I deconstructed in ‘A Most Peculiar Way’.

Part of my process is to mine traumatic incidents from my own life for my creative work. The trick is to blend these real experiences with imagined ones, usually from a different point of view than my own. This creates a safe emotional distance to work on it without burning out. As a neurospicy writer, I experience strong emotions whenever I’m writing a scene, which can be draining and can retrigger the symptoms of PTSD. So if a character is devastated by a certain event or action, I experience that same feeling in my body and mind in real time, even when I’ve stopped writing. So, while a story may start off rooted in my own life, by the time it’s sent off on submission, it becomes its own distinct thing separate from me. But hopefully it still feels real to the reader.

Next week Suzy A Kelly talks about their physical conditions, gender ambivalence and creative processes.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Hi Leslie, Happy New Year to you and Sue. This is a fascinating article. I learned a lot of new medical diagnoses, I had to look some of them up to discover exactly what they are and what they mean. Congratulations to Suzy on her writing. She has had some big issues to overcome in life and has done so admirably.

And a Happy New Year to you too! I’m glad you enjoyed Suzy’s interview. Part Two next week!