SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

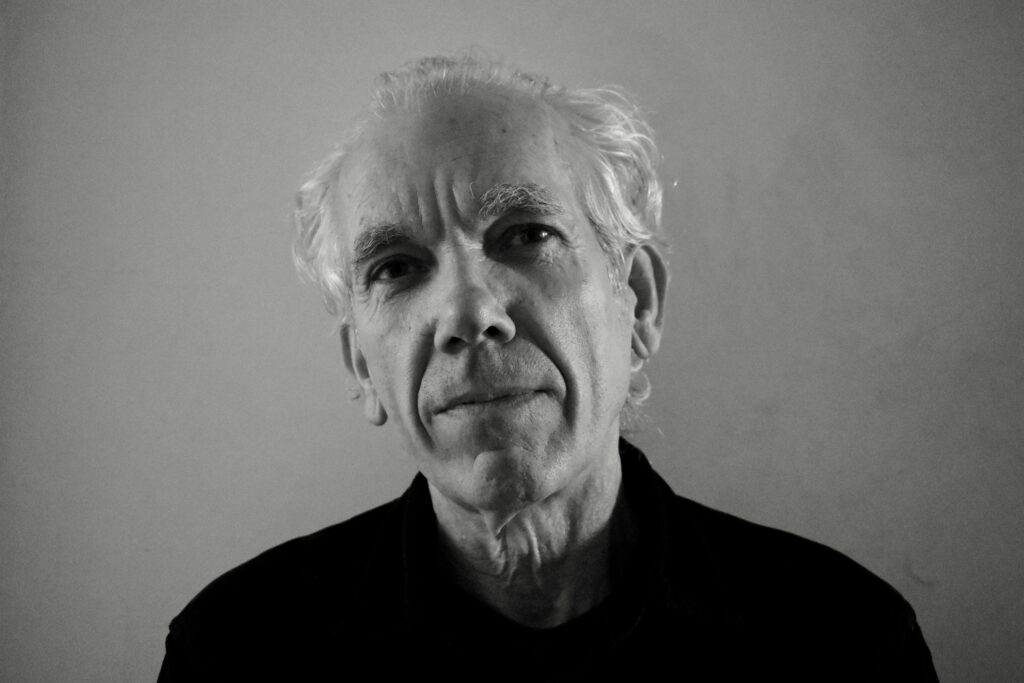

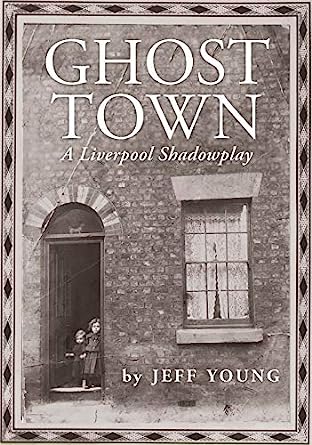

I interviewed author, scriptwriter and dramatist, Jeff Young, about Ghost Town his Liverpool-based memoir which was shortlisted for the Costa Prize. Jeff has scripted numerous BBC radio dramas and drama-documentaries as well as writing and directing innovative stage plays. In his interview, he reveals how his creative process works.

Leslie: Can you tell us the story behind the title you chose for your Costa-shortlisted memoir – ‘Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay‘. Did you have other titles in mind and why did this one fit the best?

Jeff: Ghost Town grew out of a series of essays I wrote and presented for BBC Radio 3. The series was called ‘Kaleidoscope of Muses’ and each piece was about a place, or person or artist, or artefact that had inspired me to write Muses. The working title for the book was ‘Kaleidoscope’, but quite early on I realised I was writing about ghosts, haunted places and the haunted shadows of memory. I wasn’t thinking of ‘ghosts’ in a supernatural way, more in a poetic way. Memory as an actual haunted place you could enter into, a place where memory, false and altered memory, particular atmospheres and so on haunted the shadows. This is how I perceive the city. Sometimes it’s an instinctive response, sometimes it’s a decision. Every time I walk down certain streets – or go into certain places – in the city I catch glimpses of my ancestors, of the people who have died. And I think this happens to buildings – they are imbued with hauntings. Or, I choose to manifest hauntings. I don’t actually, rationally believe in ghosts but I choose to. The city is full of ‘thin places’ where this happens the most. ‘Shadowplay’ as a subtitle came from Adrian Cooper at my publishers, Little Toller. It was a word I used somewhere in the book and it seemed to work well with ‘Ghost Town’, furthering the mood or tone of what I was trying to say. So, Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay is an altered state, a haunted hallucination you can enter.

Leslie: How did you avoid sentimentality when writing about the Liverpool you grew up in? What was the creative process that went into the book?

Jeff: It’s a hazardous territory! When writing about memory sentimentality and nostalgia are always hovering nearby. To write ‘Ghost Town’ – and it’s something I try and do with all my writing if possible – I walked the city. That way, I’m not just remembering from a distance, I’m going to the places I’m writing about and remembering closely’, in situ. I find when I do this – this visiting – it concentrates my thoughts about the past. It also tells me how that place is today, in the present moment, which gives my thoughts a clarity. I do everything I can to avoid a rose-tinted view of yesterday and in truth there was nothing to be particularly sentimental about, or nostalgic for apart from the deep love I have for some of the people I write about. My ancestors didn’t particularly have easy lives so there’s no sense of ‘the good old days’, or that the past was better than the present. There were hardships and illnesses and deaths and difficulty. I’d be doing my family a disservice if I painted their lives in a rose-tinted, sentimental way. The same goes for the city, which is ever-changing, constantly evolving – which is necessary. In every stage of the past there were good things and bad things and it certainly wasn’t better in ‘the old days.’ It’s true to say that I long for certain aspects of my own past in the city, that I miss certain places and wish I could go back. But I didn’t always have the easiest of times so I can’t look at it through the misty veil of sentimentality. And my creative process is to walk, to walk for miles, and to think as deeply as I can about who came here, what happened here, who was I then, what did it mean?

Leslie: You wrote for several major BBC radio dramas. What were they? Tell us about the ‘unwritten rules’ of radio drama and how you developed your own unique style within those constraints.

Jeff: I wrote 35 or more radio dramas and drama-documentaries. I very rarely write for radio these days because the kind of stories I want to write aren’t easy to get commissioned. For one thing, radio drama comes in waves of risk and safety, of more challenging stories and less challenging stories. I think these days it’s mostly a safe, conservative territory and I seldom even listen. It no longer interests me. But in the past, I was able to tell stories about subjects such as a riot in a Brazilian maximum security prison, or the plight of teenage girls in the drugs underworld of Mexico. I also wrote several autobiographical drama-documentaries telling stories about various adventures and misadventures in my life. The ‘unwritten rules’ are things like – radio is an intensely visual medium. This might sound like a strange thing to say but it’s actually ‘mind cinema’, you can evoke vivid visual spaces, entire landscapes, purely through the sense of sound. So, you write it visually, you make sure you’re painting the picture. Another rule is to trust the power of the human voice, the intimacy of speech and listening and the relationship between the speaker and the listener. Radio is a medium where the relationship is with each individual listener and you have to find ways to connect with that listener to draw them in. And another – related rule – is that the cut-off point in radio drama is about three minutes. If the listener isn’t drawn in to the story and the voice in three minutes they will switch off, so you have to set out your stall, cast the magic spell, find ways to seduce them into staying with you for the duration. It’s a dark art. I also spent a couple of years writing mainstream TV dramas such as Eastenders, Casualty, Doctors, and I didn’t find it nearly as interesting to write as radio drama. It lacked that magic, that dark alchemy.

Leslie: What were the most interesting live stage productions you worked on? What were the differences (both personal and observed) between that and radio work?

Jeff: Theatre when it works is magic or alchemy – creating an illusion of a version of reality that is completely unrealistic. A lot of the work I’ve done – the projects I found most interesting – didn’t even take place in theatre buildings, they were made in response to unusual or unconventional spaces and the story was drawn from and inspired by the space. Working with a collaborative team of artists, musicians, performers, choreographers and the creative team of director and technicians we would spend several months developing the language and imagery of the piece. I worked in a drained submarine dock in Barrow-in Furness making a promenade show called ‘This Red Earth’ about the imagined lives of men who once worked there. In Newcastle I worked on an enormous production in a warehouse building in Swan Hunter shipyard called ‘The Nest of Spices’. For months we gathered stories with hundreds of school children, students and community groups. We built a coal field in one of the warehouse sheds and a road full of joyriders and the ruins of cars. A more miniature approach to this kind of theatre was a show called ‘The Walking Fellow’ a two-hander telling the story of a never going to happen romance between two eccentrics. The show toured to places such as a landing stage, a boating lake and a yacht club in Ireland. Taking ideas learned in huge site-specific shows and applying them to a miniature was a way of working in a tighter focus and exploring gestures and facial expressions as much as imagery. In Liverpool I collaborated with artists and other writers to make a show in a derelict Georgian townhouse. With Kneehigh Theatre Company in Cornwall I worked on beaches, lost gardens and even a bus station in Amsterdam. These sorts of site-theatre were my favourite work and the shows involved huge amounts of research, wandering and talking to people. The process interests me as much – sometimes more – than the actual production. The biggest mainstream show I worked on was a collaboration with Pete Townsend on a staging of The Who’s album, ‘Quadrophenia’. I had worked with Pete before in radio and we had a good working relationship. I wrote the script purely visually and the songs carried the narrative. There was a huge team of performers and musicians on the show and we toured to large venues but the show never really worked.In more conventional theatre spaces my favourite show was ‘Bright Phoenix’ at the Liverpool Everyman, which shared many of the same themes as ‘Ghost Town’, in fact ‘Ghost Town’ is really a sequel to the play.

Next week, in Part 2 of his interview, Jeff Young talks about his passion for community events, teaching at the Liverpool screen school, and walking.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |