JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

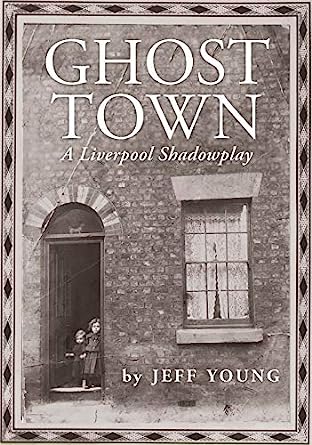

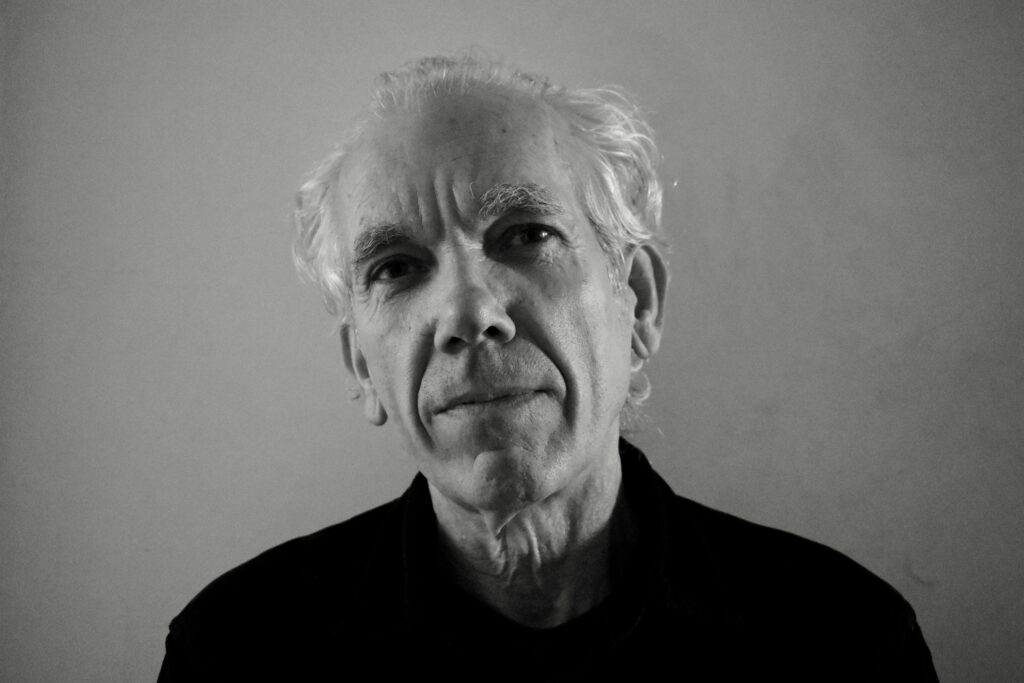

In the second part of my interview with Costa shortlisted author, scriptwriter and dramatist Jeff Young, I asked about his passion for community projects, his university teaching and his creative relationship with walking. Jeff Young has scripted numerous BBC radio dramas and TV series such as Eastenders, Casualty and Doctors as well as writing and directing innovative stage plays.

Leslie: Before writing your memoir, Ghost Town, you worked on several arts projects in Liverpool. What did you learn about yourself and working collectively from those projects?

Jeff: The arts projects I worked on almost always ended with a show or some kind of performance. City of Light, made with Liverpool Lantern Company was an enormous installation on Sefton Park Lake, made in collaboration with a large team of writers, visual artists and musicians. The community aspect was a story gathering and research process and for my part of the project I worked with older people in care homes and luncheon groups. Many of the participants had dementia and this involved a very sensitive and patient approach to story gathering, often just listening and waiting for the gold dust.

With a group of retired seafarers in New Brighton I worked with artist Alan Dunn and musician Martin Heslop to make a performance piece inspired by the work of Malcolm Lowry and the astonishing stories told by the seafarers. On a smaller scale I was writer in residence in a Birkenhead cobblers shop making a piece of work that drew on the stories told by Frank the cobbler and wider research in the area. Over the years I’ve worked on many community projects and what you learn about yourself is how to be a good listener and how to be a good asker of questions. Often, people don’t think they have a story to tell, often they are suspicious of your intentions when you first begin to work with them. In time, usually you discover that they have plenty of stories, often astonishing tales that blow your mind. Hopefully you learn to be a good ‘reader’ of people and then when their stories start to emerge you learn the skill of turning their stories into theatre or performance. In a way, you learn to be a good neighbour, or a good visitor. The idea is to honour their story, their place, their community. If you get it wrong then you’re a disruptive presence and you have abused their hospitality. If you get it right you’ve created something that you and they are proud of and it can be quite an emotional achievement. In an artists residency years ago in Weston Super Mare I worked with women in their 80’s in a luncheon group. They taught me how to embroider and they showed me the rudimentary steps of ballroom dancing. At the end if the residency we made an installation the Pier and these wonderful old women danced to the sound of a wind-up gramophone beneath bunting made from embroidered handkerchiefs. Most of those women will have passed away by now but I’ll remember them and their stories forever. I think you learn to be something else apart from being an artist – you learn to be – hopefully – a better human being.

Leslie: As the senior lecturer in Creative Writing at the Screen School of Liverpool John Moores University, what were the most important skills you taught your students?

Jeff: I taught Creative Writing at LJMU for ten years. My secret was doubt. I often – most of the time – thought that teaching writing wasn’t possible so with that doubt in mind I always questioned what we were doing in the room. Doubt is useful, healthy. If I was convinced of what I was doing I think I’d have done a bad job. What you’re ‘teaching’ – and I was always reluctant to even call myself a teacher – were certain strategies to make stories and scripts dynamic, rhythmic, flowing, oblique, strange, unexpected. We studied film, TV and radio dramas and took them to pieces, finding out how they worked, what were the mechanisms. And through testing other people’s stories in those mediums we could then apply the skills we had learned to our own stories. In workshops we would work together, have deep conversations about the scripts people were working on, and then they would take all this input away with them and make their own decisions. As a teacher I refused to place myself as a higher status practitioner above the students. I didn’t even call them students – they were writers. Even though I had more experience than the students I just put myself in the room as a fellow writer, trying to work out the same problems as they were. And we would go out into the city, looking for stories, using place as a resource for ideas and stimulation. And I often learned a much from them as they did from me. Scripts have a certain structural arithmetic about them but they also have to have magic. The process in the writing workshop is to find the magic dust through collective debate and dissection and to move on incrementally, week by week, until each member of the group has the best possible version of their script that they can achieve. It’s more like prospecting for gold than ‘teaching’. I no longer teach; I’m retired due to ill-health. The university I taught at increasingly became a business, rather than a creative environment. I naively thought that Creative Writing departments ought to be like art schools. I once said this to a Professor at the Liverpool School of Art – or John Lennon as it’s now called, and he replied, ‘Jeff, not even the Art School is like an art school anymore.’ The thing you take away from the experience is the energy and imagination of the students, the curiosity and creativity: that’s what matters. The rest of it – he said bitterly – is bureaucracy and business and I have no interest in that. When the time came, I was glad to leave.

Leslie: As a keen walker, can you describe what nature does for you and what you do for nature?

Jeff: Normally my walking is urban. I walk in cities, particularly Liverpool, and I seldom take public transport. I used to live in London and preferred to walk everywhere rather than take the tube or a bus. I’d walk from Highgate to Hackney to visit a friend or from Highgate to the South Bank, taking in the sights and sounds and smells. In Liverpool I would walk for five to ten miles a day, quite happily exploring, checking how the city was doing, how it was changing. It was also a huge part of my writing process – even when I was working on a project that wasn’t directly connected to the city I would walk. It stimulates the imagination and the rhythm of walking helps you to form sentences and paragraphs, gets you away from the desk. I always carry a pocket notebook and jot thoughts down as I go, observations, ideas, hunches. These days – because of poor health – I don’t walk anywhere near as much as I used to and it has affected my work. My imagination doesn’t ‘work’ the way it used to when I was out and about for hours. As for ‘what nature does for me and what I do for nature’ I think the answer is that I would always look for the wild when I was walking in the city – for the buddleia and other wild flowers and weeds, and for birds and animals. I have written about the imaginative rewilding of the city, sometimes in the form of performance works that are intended to act as magic spells or hexes, and birds, animals and plants feature in those works. I used to walk a lot in the countryside but I’ve never really used ‘nature’ as a canvas for writing. I suppose I used it as an escape from writing and so it had a different meaning. These days I don’t walk so much but I remember walks. Remembering and walking and writing are always connected in some way.

Next week, I interview Kimberley Hare about deep adaptation to the eco-climate polycrisis

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |