Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed disability author Grace Lapointe about her personal backstory and her writings on ableism and disability history. Grace is a senior contributor to Book Riot and wrote study materials for A Disability History of the United States. Grace’s interview is a frank exposé of disablist language, how it affects all of us, and what makes for a healthy, inclusive society.

Leslie: Tell us about your experiences as a person with a disability. How have your early social experiences led to the campaigner, thinker and prolific writer/commentator you are today?

Grace: I was born with cerebral palsy in 1989. I’m an only child, and my parents told me about my disability by the time I was around 2 years old. They never stigmatized it or let anyone pity me for it. Disability is one important aspect of my identity and narrative. In 1993, when I was 3 years old and in preschool, I was photographed for my local newspaper at one of my physical therapy sessions. My first “published” work was an essay that I wrote and illustrated when I was seven, about my experiences with therapeutic horseback riding. My therapeutic riding center published it. They printed it in their newsletter. I always believed I had interesting stories to tell and had family and mentors who encouraged me.

I also always knew a lot of other disabled people. I felt isolated sometimes growing up, but it would have been much worse if I hadn’t been part of disabled communities. I’ve always been very opinionated. I noticed when friends and I were treated unfairly because we were disabled, and this is partly where my interest in social change started. My elementary school was diverse and always included me, but then I briefly went to a school that deliberately excluded me.

I’ve also always been a writer, since I was little. Then, from age 12-15 in 2001-04, I wrote an unpublishable sci-fi novel about the world’s first human clone. Some of my feelings about ableism (such as being considered uncanny, exceptional, and subjected to unwanted attention) made my way into the characters. But then I felt creatively burned out for years.

When I was a sophomore at Stonehill College in 2009, I took Jared Green’s fiction writing class. Jared is still my friend and mentor. He encouraged me to submit stories I wrote for his classes for publication in literary journals. Years after I finished them, they finally were published in litmags. My friend Chris Reardon, who’s disabled too, was in my workshop group in that class. Chris and I gave each other constructive feedback a lot. Jared was enthusiastic that Chris and I both wrote fiction about our experiences and identities being disabled. It wasn’t a popular perspective in mainstream culture at the time. All three of us have published fiction in litmags and keep in touch.

Leslie: Tell us about the marginalized history of disability and how you discovered your own identity through it.

Grace: Disability history is everywhere and intersects with every other marginalized group. In 2013, I interned at Beacon Press in Boston, MA and wrote study materials for A Disability History of the United States by Kim E. Nielsen. I learned a lot from her book, including about the institutionalization and sterilization of disabled people in recent history, and the “ugly laws,” which criminalized visibly disabled people in public as recently as the 1970s. In 2018, Vilissa Thompson wrote that many people still don’t think of famous Black Americans, like Harriet Tubman, as disabled.

Disability history is still ongoing, of course. 33 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed, many businesses barely provide the minimum in terms of access. Civil rights should never be optional or subject to more powerful people’s whims. The ADA passed the year after I was born. Currently, governments minimizing COVID-19 and climate change are killing and disabling people through deliberate inaction.

Leslie: What are the key aspects of ableist language that you’ve written about in your essays? How does ableist language sneak into our everyday thinking?

Grace: There are slurs that were once medical diagnoses, like the r-word for intellectual disabilities, and sp*z, which refers to the type of cerebral palsy I have (with painful muscle spasms).

In 2019, I blogged that people use ableist metaphors so often, they forget they’re figurative, not literal. This is a problem because it conflates disability with negative traits and actions. I used the cliches “turned a blind eye” and “fell on deaf ears” as examples. Blindness and deafness have nothing to do with deliberately ignoring something, but those expressions link them. Many people also use stigmatized psychiatric symptoms as synonyms for evil, which further depicts mentally ill people as evil or violent. I know it might seem like we’re arguing semantics, but ableist language both reflects and reinforces ableist myths. It sneaks into our thinking because it contributes to the idea that disabled people are evil, scary, or inferior.

Basically, I wish people would stop using people’s identities or appearances as insults. I know words like “idiot” and “moron” were used by eugenicists. Not everyone knows that, of course. But you don’t need to know that history to try to stop insulting people’s intelligence. When a politician or celebrity does something they dislike, some people use that as an excuse to be bigoted, and that’s not OK.

Leslie: Two questions in one! How has ‘monstering’ and ‘othering’ manifested itself in your life and how we can change these attitudes? How does ableism debase disabled people? What have you discovered about yourself in exploring your ‘inner ableist shadow’?

Grace: A lot of us talk about internalized ableism (towards yourself) and lateral ableism (towards other people, often with different disabilities). These two forms of ableism feed on each other. We all have to unlearn them and other cultural biases.

I’ve called ableism a form of abjection which debases individuals and damages their sense of self. Julia Kristeva described sexism as abjection, but I applied her definitions to ableism in 2020. Basically, it’s the idea that you’re not a real person or that other people consider you inferior or subhuman.

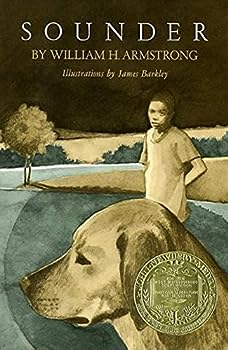

I’ve written a lot about the lack of disabled characters by disabled authors when I was a child in the 1990s. This drove me to write, even as a kid. Then, when I was 9, I read a “humorous” body-swapping novel for children. The central “joke” is a non-disabled boy switching bodies with a dog. His friends then pretend this dog in a human body is a disabled child because he’s drooling, incontinent, not speaking, and walking “differently.”

Leslie: What is Book Riot, and how long have you written for it?

Grace: Book Riot (BR) describes itself as “the largest independent literary site in North America.” It was founded in 2011 and gets 3 million monthly visitors. https://bookriot.com/about/ I became a freelance contributor for BR in January 2018 and was promoted to a senior contributor in late 2022. I’ve written over 110 articles for them. We don’t write book reviews per se anymore because lots of sites do that. I love to analyze literature, and I like writing short, accessible essays and lists for BR. I can explore my interests, including sci-fi/fantasy, feminism, and disability and ableism in literature. It led me to a much bigger audience for all my work, even for other sites!

Leslie: Tell us about the lighter side, the fun side of your life.

Grace: I know it’s hard to tell from my earlier responses, but I think I’m hilarious. When all my social media was public, I was afraid some people thought I was a meme or fandom account, not a writer. I think in corny, topical puns sometimes. For example: “Me when someone tries to rename Twitter: [a pic of Sesame Street’s Big Bird singing, “It’s time to Tweet!”] Also, with cerebral palsy, I sometimes physically can’t stop laughing at my own jokes. My friends and family can confirm this.

I recently watched a lot of Doctor Who. I even wrote fanfic of it. I also love adult coloring books.

I also love music. I’m always listening to music or singing. I have like 5 YouTube followers. I don’t always have the energy for these hobbies, but I love them.

Next week I interview international actor, broadcaster and cabaret artist Frank Loman,

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |