JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

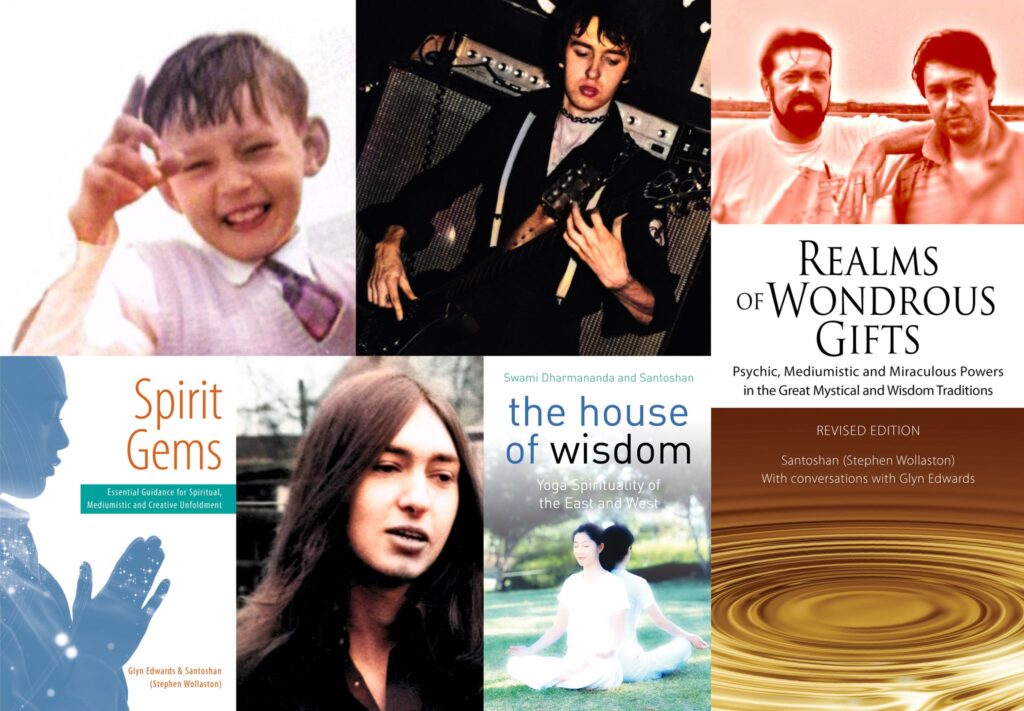

I interviewed Stephen Wollaston, aka Santoshan, a OneSpirit Interfaith Foundation minister, who holds a BA degree in religious studies and is trained in psychosynthesis counselling. Stephen is the current chair of GreenSpirit’s Publications Committee and has coauthored and edited more than a dozen books on different areas of Eastern and Western spirituality.

In Part One of his interview, Stephen talks about his creative and spiritual development, including his time playing bass guitar for an early punk rock band, The Wasps.

Leslie: What’s the story behind your chosen name Santoshan? Where did it come from, what’s its meaning and why do you feel it fits you?

Stephen: The name Santoshan was given to me in the mid-90s in a naming ceremony by a female English swami – Swami Dharmananda Saraswati Maharaj – who was a teacher from the Bihar School of Yoga. She in fact later asked me to co-write the book ‘The House of Wisdom: Yoga Spirituality of the East and West’ with her, which was published in 2007. The name means ‘contentment’ and is given as something to aim for rather than simply being a statement about someone.

I have actually had to reflect upon and arrive at my own understanding of the word ‘contentment’. There’s a saying by the British philosopher John Stuart Mill that mentions how ‘It is better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’. This makes sense to me as life isn’t perfect and there is suffering and injustice in the world, which to me would seem callous if we were to just sit back and not care or empathise with other humans and our more-than-human relations in their suffering, as well as own inflicted wounds and work on healing ourselves. To my understanding, various Yoga traditions would acknowledge this, and therefore means it’s not about spiritual bypassing, which ignores the shadow, but about ways of being that recognise and own it, and lead to compassionate actions in the world and seeks to bring about change.

The name Santoshan I used for the very first book I co-authored with a long-time best friend, legendary progressive medium and former Benedictine monk Glyn Edwards, which was published in 1999 under the title ‘Tune in to Your Spiritual Potential’ and later retitled by Glyn and me in 2011 as ‘The Spirit World in Plain English’. He asked me if I’d work with him on the book. But I was aware that writing with someone as well-known as him within the Spiritualist movement, might give the impression I had a similar background. I decided to use my spiritual/Yoga name to show there was a difference, although it ought to be said that Glyn was always wide and inclusive in his teachings, had deep interest in Yogic wisdom himself, and was also given a spiritual/Yogic name by Swamiji at the ceremony I mentioned. Glyn and I then wrote a second book, and I did the one with Swamiji and used the name for those as well, and have continued to do so for others. Although I don’t usually like labels – neither did Glyn – it answers some questions people may have about my spiritual background and interests.

Leslie: Tell us about the earliest signs of your interest in art, graphic design, nature and spirituality. What has changed in your perception of these areas from childhood to today?

Stephen: From an early age I pencil-sketched reams of pictures whenever I could, quite naturally discovered ‘art as meditation’, cherished quiet moments in my parents’ East End council house garden, ran energetically around with friends and my family’s dog in local grassland parks and nearby exquisite densely wooded regions of Epping Forest, and enjoyed family outings to the sea or countryside. I would lose myself for hours drawing, being in amazing and magical green spaces, creating, playing music when I took up bass guitar, or simply staring wondrously at the shapes of mesmerising morphing clouds and the gyrating activity of bees hopping from flower to flower while they made intriguing buzzsaw-like sounds. Back then I hadn’t discovered how different facets of life, creativity, Nature, and transpersonal experiences could come together and be seen as integral facets of important Earth-centred spiritualities that radically address the needs of our current age.

Those early years of creative drawing were what led me to later train as a typographic designer at the London College of Printing and join a graphics partnership in London Docklands. Then the 90s’ recession hit the design industry badly. Rather than be jobless, I did a degree in religious studies and a postgraduate teachers’ certificate at King’s College London, and have taught various humanities subjects such as world religions and psychology in schools, and English language skills for war refugees in adult education, along with less frequent work on typographic projects.

Before this, I was in various semi-known rock bands from the late 60s to late 70s, which brought me into contact with an older musician who had an interest in Eastern spirituality and meditation practices. It wasn’t long before I experienced expanded states of awareness that opened me to new ways of being, and to a life-changing vivid peak experience at 19 while meditating alone in my parents’ backroom, which overlooked the garden. Things happened unexpectedly one summer’s afternoon when I became conscious of a sacred presence, of which the ticking of a clock in the room, the singing of birds outside, the silence of the house, what felt like another mind widening, communing and blending with mine, and a clear awareness of both my physical body and being more than it, all became intertwined facets of one another. The experience has never left me and led me to explore various spiritual paths such as Yogic wisdom, Buddhist teachings, and the creation-centred works (not to be confused with ‘Creationism’ that denies the insights of contemporary science) of the activist, radical theologian and Episcopal priest Matthew Fox.

When I looked deeply into the mystical traditions of India and Christianity, I discovered teachings that struck deep chords within me. I became aware of various influential eco-spiritual prophets such as Thomas Berry, and began to investigate the benefits of spiritual retreats at different centres. One modest small community had 80 acres of wild forest surrounding it. It was there while on a regular morning walk under a cathedral-like ceiling of tree branches stretching over a mottled light-grey and brown stony forest path that I realised I was finding a deeper serenity and spirituality amongst Mother Nature than in many communities’ chapels. This wasn’t to say that creative rituals that looked for deeper ways to touch life profoundly didn’t have value. But somehow the natural world was calling me to another mystery that I felt was absent from some of the most moving church and temple services.

Leslie: How did your punk rock performance days come about? What stories best characterise that period of your life? How do you connect loud rebellious music with peace, spirituality and meditation?

Stephen: I was asked if I’d like to play bass guitar when I was 13 by a drummer, John Richardson, who was two-years-older than me and went to the same boys’ school as I did in the East End of London. He’d been playing drums since he was about six and had formed a band of other older musicians that needed a bass player. He told me that the two guitarists in his band would help me learn how to play. I saved up with money from a paper round and bought a second-hand bass guitar for £10, and got a cheap bass amp and speaker on hire purchase.

I’m still in touch with John, who later did session work for people such as Dennis Stratton from Iron Maiden, Dave Edmonds, and Rory Gallagher. The reason John approached me was because I was fairly knowledgeable about rock and English blues bands because of my older brother and had already seen a few known acts live in local clubs – even though I was underage to have been allowed entrance – and dressed fashionably. This was the late 60s when a lot of school kids weren’t so interested in rock music or blues. I later played bass guitar in a progressive rock band in the mid-70s that was briefly fronted by the eccentric English painter, quirky semi-surrealist poet, musician and singer Lady June, who was looking for a band to promote her album ‘Linguistic Leprosy’ (produced and contributed to by Kevin Ayes and Brian Eno) so joined forces with the group I was in, Elysium, who also wrote their own material.

After that I met up with my drummer friend John again, who’d been playing on the pub rock circuit and brought with him a highly talented guitarist he’d been working with, Dell May. We then put an ad in the Melody Maker for a singer and met Jesse Lynn-Dean and formed the punk rock band The Wasps. This was in the early spring of ’76, just as punk was surfacing in the UK, and it seemed right to embrace what was happening at that time.

The Wasps went on to help pioneer punk rock when it was unpopular with most audiences. We played at venues such as the Marquee, Camden Town Music Machine, Covent Garden Roxy, Chislehurst Caves and the BBC (for the John Peel show). Most venues drew a different mix of people, from unemployed workers to middle-class students and young white-collar staff, looking to experience a vibrant live act in an intimate setting. In recent decades the Internet has kept an interest in the original band and line-up alive. I remained The Wasps’ principal electric bass guitarist for three years, and played on what have become two classic anthems and collectable singles of the early punk era: Teenage Treats and Can’t Wait ’til ’78 (released from the Live at the Vortex album). For ethical reasons and a growing awareness, I also became a vegetarian and, because of a recent mild health problem, was able to keep more strictly to a vegetarian diet then than I am able to do now.

On the whole the music charts were full of superficial numbers at that time, and more competent popular rock groups had become self-indulgent, playing long numbers to crowds who no longer danced, but instead sat down. Punk emerged as a response to this. Originally there were no punk records to listen to. If you wanted to hear it, you had to find a venue where a few early groups such as The Wasps played it live.

Occasionally I’m asked your question about how I was able to come to terms with what some see as two conflicting areas: punk rock and spirituality. I had after all been involved in what is seen as an aggressive style of music that often has lyrics advocating violence. It is a fair point. At Shrewsbury, for instance, the local casualty department had an influx of people with minor injuries from scuffles that broke out at a Wasps concert and led to us being banned from playing at the Civic Centre again. Such violence obviously concerned both me and the other group members and we subsequently took time off the road and concentrated on new material that had less of an anarchic message and consciously toned-down our punk image.

Contrary to what some might think, none of us would have condoned physical violence. What we hadn’t foreseen through the naivety of youth was that a few audience members would use the music as an excuse to take things too literally. Though the majority of our concerts were in fact peaceful and drew people together from various social backgrounds (my girlfriend back then was from a middle-class family for instance). Punk, to us, was a creative force and didn’t imply inflicting harm. We also respected musicians from other fields such as the dub scene, which was another underground movement at that time, and got DJs at our concerts to play records in the genre. We were even asked to support the African band, Third World, three times and got on well with them – more than we did with some punk bands who saw us as rivals. I’m pleased to say we never got involved in rivalry games. We were confident in our material and style of playing so didn’t feel threatened by other acts.

We are all of course more than the psychological stereotypes that others may seek to impose on us. I’ve since met an Anglican priest and heard about other men and women of the cloth who claimed to be fans of punk rock. There’s even a book on Zen that includes it in its subtitle, ‘Hardcore Zen’ by Brad Warner. Creativity has taken on many forms in my life and is a core facet of my spirituality – even when expressed in the wildness of punk. I didn’t fully understand how this was so at the time, but nonetheless profoundly felt it.

For me, what could be seen as a punk spirituality, or at least a highly radical one, is a spirituality that is prepared to challenge dumbed-down teachings – particularly when movements cease to encourage active compassionate engagement and become too inward-looking, comfortable and rigid in their beliefs – and questions the status quo and outdated teachings that are no longer pertinent to our age. I’m thinking here in particular of antiquated gay and gender beliefs that have side-tracked Christianity and taken its focus away from what is important, such as unity in diversity, global warming, wars, famine, injustice, poverty and the mass destruction of thousands of species every day! Why don’t we see more righteous anger in action for wholesome ways forward?

I find it interesting that ideas of going with the flow are at times promoted, which can be beneficial if taken to mean living at one with ourselves, others and the natural world – to ‘be present to the planet in a mutually beneficial manner’, as Thomas Berry advocated. But can also be seen as damaging if interpreted as accepting the unacceptable and doing nothing with our gifts to bring about healthy changes in the world. Our actions can of course be small but significant, such as making ethical choices in how we travel, what we buy and choose to eat (less dead animals hopefully). We can also petition, demonstrate and spread Earth-centred awareness in our local communities. In spite of realising how living a contemporary and challenging spirituality will inevitably rock the boat, since my punk years I’ve increasingly tried to help promote and support green/creation-centred wisdom where I can, with the skills and knowledge I have to offer.

Next week, in Part Two, Stephen talks about Psychosynthesis, GreenSpirit and eco-justice.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

I have so enjoyed reading this interview. It touches on aspects of spirituality that I too have experienced over the years. Thank you

Thank you, Raine! 🙂 🙂 🙂