Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed artist, writer, curator and educator Sarah Chapman who led and directed The Arts Institute in Plymouth. Sarah tells the story of working with internationally famous artists but deciding to walk away and focus on her own ‘biophilic’ art and her secret drawing, practised in her studio.

Leslie: Can you tell the story of how your “art as obsession” began, grew and developed? What were the most important incidents/events that drove your artistic development?

Sarah: I veer towards introversion and like to observe and find the connections between and within things, including people. The term obsession in the context of my work refers to deep observation. I am fascinated by the idea of change and the rhythmic vitality of things. Change is a constant: light, atmosphere, hand and eye. Nothing stays the same. The more you look, the more you see, including understanding how you see. As far as I can remember, I always wanted to be an artist. This may have been compounded by some early emotional experiences and social disparities experienced as a child. Either way, I learnt quite young that judgements concerning taste, behaviour and etiquette are made-up and subject to change depending on the prevailing wind and whether you empowered to say differently.

Leslie: Choosing some artworks to represent your current obsession with rocks and deep time, can you describe how they came about?

Sarah: I titled a body of work ‘This Rock saved My Life’ because it really did. At the age of 50 I found myself at the centre of a perfect storm of major life events, suffering from grief, divorce, loss of job and menopause during the Covid lockdown. At my lowest point, not knowing what I was going to do, I fixated on a lump of granite from a collection of stones on my desk. Feeling its weight, its certainty and coldness, I began to draw it from multiple angles, noting how the slightest movement, even a breath, provided a different perspective. It gave me a purpose and helped me find a way through. Even when I thought I was fixed, drawing the stone made me realise I wasn’t. At the same time, I was walking on Dartmoor on my own, and with a few close friends and family. On the day my father died I walked up to Sheepstor with my children because I didn’t know where else to go. The isolation of the moor and the solidity and definitiveness of the granite rocks helped to put things in perspective: providing a reminder of the vastness and the power of forces much bigger than us. It was as close to religion or a spiritual feeling that I could find.

Leslie: Looking back on previous preoccupations, which artworks stand out? Why them?

Sarah: Common themes that keep reoccurring in my work concern the body as a permeable vessel and how interconnected we are to our environment. ‘Spirewell’ (2018-2020) was a series of painted-over photographs printed on aluminium that explored the memory of a pond close to where I had spent my formative teenage years. The skin and surface tension of water, not dissimilar to the photographic surface, became an analogy for the interior body and the memories held within: separated by a permeable viscous divide, both contain visible and non-visible spaces, with an above and below, hidden depths and undercurrents. It was around this time that I began to experiment with creative writing and spoken word, merging poetry, story and myth loosely based on biographical experiences to explore bodily knowledge and change, a series of writings that I titled ‘SlipSkin’.

Leslie: What have been the highlights of your professional day job curating and delivering a public arts and education programmes? Why them?

Sarah: During my curatorial career I had the privilege of working with some wonderful artists, including high profile international artists, lesser-known names and those just starting out. My motivation was to bring different artists together to provide new ways of looking or thinking about a subject or idea that hopefully excited and extended people’s experiences about art. Finding ways to increase access to art and culture was integral to what I did. The White Cube Gallery, for instance, can sometimes feel like a high church and stepping over the threshold can be daunting. How to break down this barrier whilst giving artists the freedom to do their magic was my focus, and I found that the most successful projects I curated or commissioned had bridges to connect these two aspects built into them from the outset. With this in mind, the memorable highlights have to be the Big Read projects, namely www.mobydikbigread.com (2012) and www.ancientmarinerbigread.com (2020) both of which went global, receiving world-wide reviews and over 10 million hits. Both projects were collaborations with artist Angela Cockayne and author Philip Hoare, whose combined expertise and passion brought in a fantastic array of artists, musicians, writers, performers, speakers, scientists and researchers which, supported by a wonderful, open-minded and inventive project team (who I’d work with again in a heartbeat) made both Big Reads not only fun to work on but ground-breaking in what they achieved.

Leslie: Tell us about dRAWing Space and your year of drawing at the Royal Drawing School, London. What led to this change in direction?

Sarah: I’d been working in higher education and the public art sector for twenty plus years. I’d gotten into arts administration to support my own practice as an artist but. as is often the way, I got pulled sideways. The financial security and fancy titles offered by academia are very alluring. I was still creating on the sidelines, but under pressure to produce work that fitted within academic criteria and so I completed a PhD that examined the relationship between photography and painting. Drawing was my dirty little secret that I did at home. In the end, however, the internal conflict became too much. It felt like I was denying something essential, so I decided to jump ship and reverse my work-life balance to make my art practice the main driver. This change in direction felt immensely scary. I had to let go of my ego, step into the unknown and start again. Thankfully, it turned out to be the best decision ever. It allowed me to reconnect and start to see freshly and without timidity. Moreover, I’m glad it started with a rock that was born in fire and crushed under immense pressure. As an older woman, the analogy seems apt.

To find a way back into my own creative work, I realised I needed to unlearn a lot of things and to also set a discipline of committing to a regular studio practice. The Royal Drawing School, London, offered an intensive year-long drawing programme that demanded no theory or writing, just the challenge and rigour of exploring drawing in all its guises, from observation, memory, representational, abstraction and experimental. It gave me the time to flex and strengthen old muscles whilst seeding ideas and opening up a new network of artists and opportunities.

Back in Plymouth, I was keen to use my professional experience to do something that removed the barriers and hierarchies surrounding creativity. Drawing is a fundamental activity, which underpins so many creative processes including non-art subjects, and I had met many people throughout my career who said they used to draw and would like to do so again, or wanted to learn but had been put off by bad educational experiences. Equally, many artist friends said they wanted a supportive space to practice observational drawing as an adjunct to their creative work. Hence, dRAWing Space was born, an initiative that provides a series of drawing workshops for all ages across the south-west. It’s still very much in the early stages and I’d like to see it develop into a wider artist-led collective that both supports artists and provides people with different workshop experiences.

Leslie: What would you like to add about Contorted Bodies, Spirewell, Slipskin, your writing, or any other aspects of your creative life you haven’t covered so far in your answers?

Sarah: The last few years have been a real journey, and I’m still trying to find a way to articulate in writing what my interests are. The mutability and permeability of the body, alongside co-dwelling and co-existence with more-than-human forms seems to be a central theme. I like the word ‘biophilia,’ which literally means the love of living things and which is hardwired into our DNA driving us to seek out connections with nature.

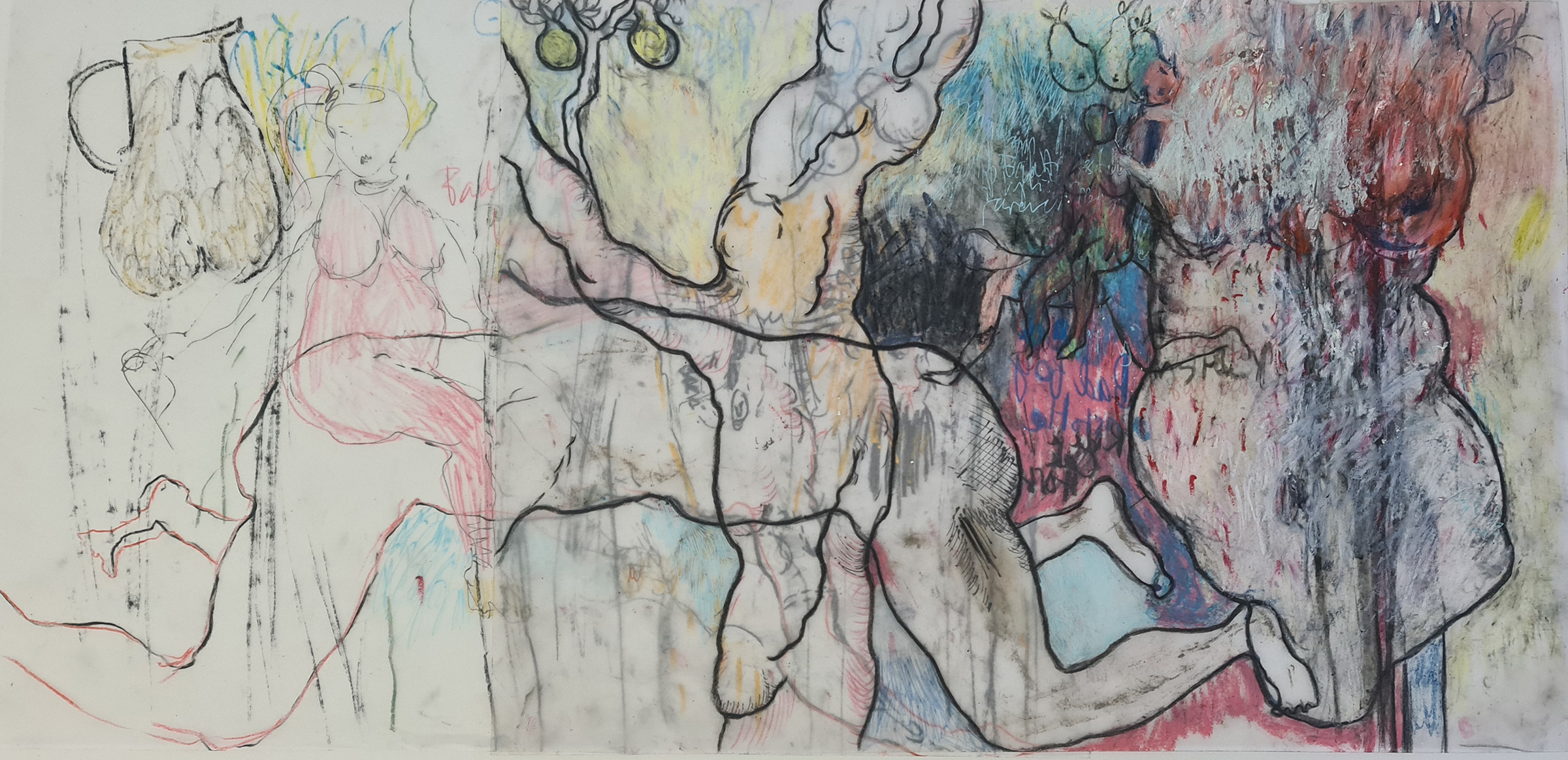

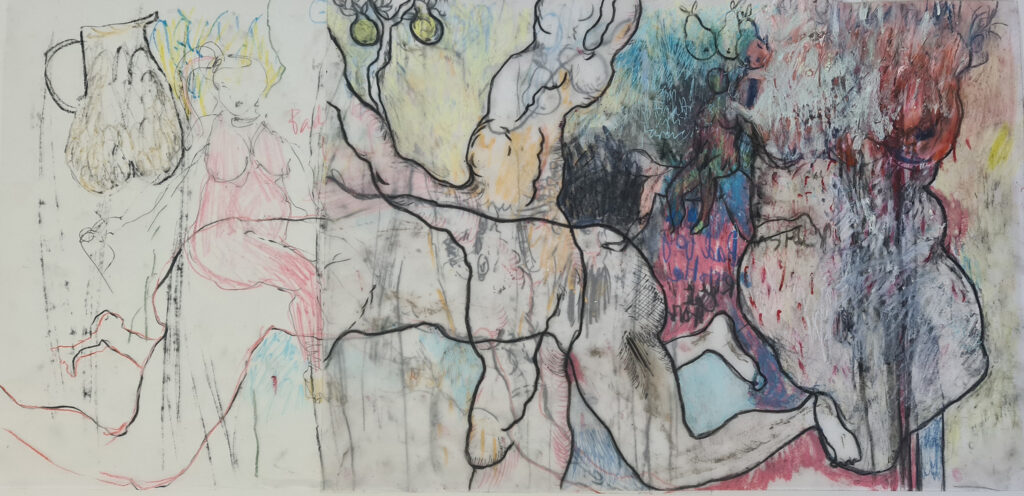

Recent works include ‘Contorted Bodies’, a series of drawings that explore the ways in which we distort and adorn the body from Palaeolithic ‘Venus’ figurines to pole dancing – I’m interested in female bodily experiences from the visceral to the mythical. I’ve also become obsessed by an old apple tree in my garden, once again it’s fascinating to draw from different perspectives and has got me thinking further about myth and animism.

Writing remains very important, with ‘SlipSkin’ taking the shape of a sequenced text that has prompted a series of drawings about memory, sensuality and motherhood.

I have recently been awarded an artist residency by the Royal Drawing School based at Dumfries House, Scotland, during February, where I will have a studio and access to their printing facility, which is an area I am keen to explore in my work. I also have a group exhibition with my cohort from the Royal Drawing School in West Kensington, London, in March this year.

Next week I interview Marian Van Eyk McCain who, on her Elderwoman site, discusses women aging and ‘sage-ing’.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |