Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed artist Bridget Bailey about her extraordinary nature-based hats, originally sold by Liberty of London, and her textile flora and fauna, exhibited at Fortnum and Mason, Jagggedart, London, and the Royal Academy. Bridget talks about how she learned millinery, her artistic techniques and methods, and her more recent insect-and-plant inspired creations.

Leslie: How did your upbringing develop your interest in ‘finds’ and the close-up study of nature? What were the messages you were receiving about art, in all its forms, and its relationship to the world?

Bridget: I grew up in Sandsend in North Yorkshire and spent lots of time on the moors looking for weird and wonderful caterpillars, or beach-combing for shells. My elder sisters were always better at finding things than me, and I developed a passion for nature and collecting, maybe as a way of trying to catch up. We were always encouraged to do creative things and mum was always drawing and painting, so art was there as a thing one could do. She was also a passionate gardener and kept some hens and turkeys with beautiful feathers. I still have a hoard of them tucked away and collect many other oddities, from dead bees to cats’ whiskers. The whiskers make delicate antennae for moths and the insects are good to scrutinize for reference.

Leslie: Tell us the story, please, of how and why your millinery skills developed.

Bridget: I studied textiles at Farnham. The course was very hands-on and I loved experimenting and seeing what fabrics can do. I specialized in a collection of fabrics combining pleat and print. I moved to London 1984 and set up a studio doing pleating. I made collections of scarves for Liberty but, to be honest, I was a bit scared of fashion. My plan was to find designers to use my fabrics for garments. I took my fabric collection to show Jean Muir and she said “Make me some hats”. So that got me into hat-making – in at the deep end using my pleating techniques to make sculptural headpieces and learning as I went along. I made hats for her collections as a freelancer for the following five years.

Leslie: What have been the main differences between manufacturing hats and handmaking them?

Bridget: I spent the next 20 years making more commercial millinery, selling to department stores and producing big orders, working with factories in Luton and employing people to help with production, although I was always doing some of the making myself. Nothing stays the same and markets changed for hats around 2004, with much of the manufacturing moving abroad. The big orders vanished and I began to make more special one-off pieces, trying to find a way to make more refined work that looked worth the time it took to hand make.

I’m summing up the difference in the two ways of working with lilies, as they’re a design I’ve made over my whole career.

Wholesale Lily – one year around 1998, I had to make a thousand of them and I wish I had a proper photo of the lily mountain, but it was pre-digital… I had a deadline and a certain number to make each day, and if I got behind the total went up. I’d often dream about deadlines at this time, and my dreams were very much like my actual days. The same idea repeated lots times does give a level of fitness to boredom and really hones making-skills.

Art Hat Lily was on a hat that was made for the Unveiled – The Craft Millinery exhibition at the Art Workers’ Guild in 2019. It’s inspired by the thought of gardening at night, the moths coming to the lily perfume and moonlight making the silvery colour palette – and that’s just the ideas, not all the construction issues… it’s lots of things going into one piece and hoping to be both thought-provoking and original in making methods.

Leslie: What are the standard techniques that go into high-end millinery? How have you adapted the technical and emotional skills that underpinned your hat making to your art involving nature?

Bridget: Dyeing for colour-matching is just as important for silk peas matching their straw pods as it was to match a customer’s outfit. And the way the edges of the peapods are turned-in is a typical millinery finish with a wire rolled into it, just as there would be in the edge of a hat brim. Hopefully it looks flowing and effortless but it’s very tough on the hands. That sums up so much of the making side of what millinery. It takes a lot of effort to look effortless.

The sculptural quality of millinery is still a big influence. Blocking – the technique used for shaping hats – can be scaled down make the ‘x-ray’ peas. And hat-making is so much about different views and angles. The way the line of a hat behaves in relation the face is make or break. That’s definitely still present in the work I do now, from swirl and flow in the lines of an artwork to the curve at the end of a pea pod.

Because millinery is a niche profession, many people don’t find it until they’ve had previous training or career. I took the skills of textiles with me into millinery, but now I’m taking the skills of millinery into my artworks. I want to show people the language and materials of millinery and how beautiful they can be, without the issue of whether they need a hat or not.

Leslie: How and what have your learned from studying nature and having an allotment and a hen?

Bridget: I live in London and besides having the allotment I keep a hen. In a small way I’ve brought the countryside into London instead of moving out to it.

Hens have a very different view of gardening. They love to eat weeds. They like chickweed and sow-thistle and they love the dandelion heads when the seeds are ripe. They know that rye grass has the most protein in it, even though couch grass looks more juicy and tender.

I never studied biology at school, but I grew up on a farm and this reminds me of my dad talking about types of grass and about mowing the hay at the right time, to catch the nutrients before the seeds ripen.

It’s got me thinking more about how nature works as well as how it looks.

Leslie: What have you learned about yourself and your art from teaching masterclasses?

Bridget: I started teaching around 2010. Any sooner and I’d have felt like a fraud as I’m mostly self taught where the millinery is concerned. I’ve learned so much from teaching and it’s become a welcome contrast to the very isolated way I make my artworks.

I’m always having to ask myself “What the hell it is I’m doing to make it come out the way it does!” I enjoy the challenge of explaining these very physical things by words or diagrams, or sometimes just a grunt. I never know which method or metaphor is going to help and this composite way of explaining is has got me thinking about making work from different viewpoints. It’s sparked an interest in projects that investigate the creative process itself in more detail.

Leslie: Can you explain, with examples, what you mean by your work ‘translates’ nature and your work has ‘evolved’?

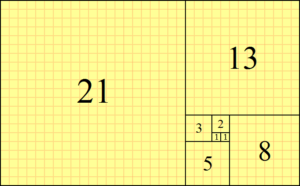

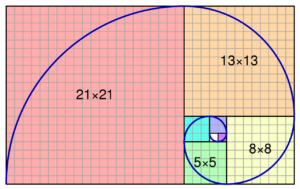

Bridget: I’d started sticking needles into a paper ball to try and work out the Fibonacci spiral, focusing on the structure of a flower, instead of being diverted by the beauty of the petals. The eyes of the needles were very straight and blunt looking and I tried threading them with wire. Suddenly the swirl of the wire in the needles suggested the bones of a chrysanthemum. A sort of 3D drawing, explaining the principle without trying to replicate nature in a realistic way.

There’s something rather organic and botanical about the way ideas can have another growth-stage. Over time, a finished artwork becomes the sample stage of the next piece.

Leslie: Please describe instances that you describe as ‘making was investigating’ and where your materials and subject converged.

Bridget: I’ve been looking at birds’ eggs and reading about what makes the colours and the patterns. They’re made with layers of calcium and threads of pigment and I tried layering silks together and letting the under-colours glow through. The patterns are so ‘unconscious’ in the way they’re formed. I didn’t want to try to copy them and instead I tried trapping feathers under silk to represent the pattern, using one aspect of birds to describe another.

Reading a bit more, I learned that each bird even within the same species has a sort of personal egg pattern and that many collectors would treasure having a collection of eggs from the same actual bird. I did notice when I had two hens that they each had their own particular egg shape. For my next egg collection I’m thinking of using a print of my own fingerprint to represent the personal nature of pattern on the eggs.

Leslie: Can you give us a few examples of the ‘micro-fitness’ and the ‘intense repetitive doing’ you’ve had to cultivate. Given the demands involved, why do you continue putting so much of yourself into your art?

Bridget: Binding insect legs is a good example of micro-fitness. The legs are made by lashing together diminishing gauges of wire with a wire that’s so fine it’s like working with a strand of hair. Making them involves walking the tightrope between gripping with hands in awkward shapes while keeping the right tension, so as not to break the binding wire.

Some of my artworks are made from a mass of individual stems. These involve a lot of repetitive work, and have to be stitched into place onto card individually, in two or three places with invisible thread. Each time I make a stitch I have to move all the other stems to pick up the card, and so there is an ‘arrangement choreography’ to manage, as well as the mass of tiny stitches.

I’ve made things for a long time and it’s challenging, but rather addictive to keep evolving. I’m always hoping the next thing will be a better one, not just in making but in the thinking too.

Leslie: Would you like to characterise your own creative discipline and your history as a maker/artist in response to this Dylan Thomas poem:

In my craft or sullen art / exercised in the still night / When only the moon rages / and the lovers lie abed / With all their griefs in their arms, / I labour by singing light / Not for ambition or bread / Or the strut and trade of charms / On the ivory stages / But for the common wages / Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart / From the raging moon I write / On these spindrift pages / Nor for the towering dead / With their nightingales and psalms / But for the lovers, their arms / Round the griefs of the ages, / Who pay no praise or wages / Nor heed my craft or art.

Bridget: At times I’ve looked at my relationship to my work as if it’s a relationship with another person. Is it a weird love affair? When it’s going well and travelling, hopefully its wonderful protection against other difficulties, but when it’s stuck and all is going wrong it can really spoil everything else. Is it my wayward teenager who I keep supporting, although they don’t always pay me back?

In the hard times I really have asked myself why I need my self-worth and approval to come through this creative filter, and why I can’t be more content having good friends and simple pleasures.

As it’s not about money or the bits of praise, although of course they’re needed, I think for me, working as an artist, is becoming more about communicating and inspiring others to notice things. It’s actually quite a gift not to be satisfied and to want to keep trying and evolving.

Next week I interview Kelsey Josund about working in Silicon Valley, California and her book Platformed, a futuristic fantasy related to her work experiences.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

I’ve never thought about hat making before, Leslie. It is very interesting to learn more and consider Brigid’s methods and thoughts. Her last comment about her self worth and personal approval coming from her art work resonates with me.

Yes, I felt that last remark was so true! Thank you, Robbie.