SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

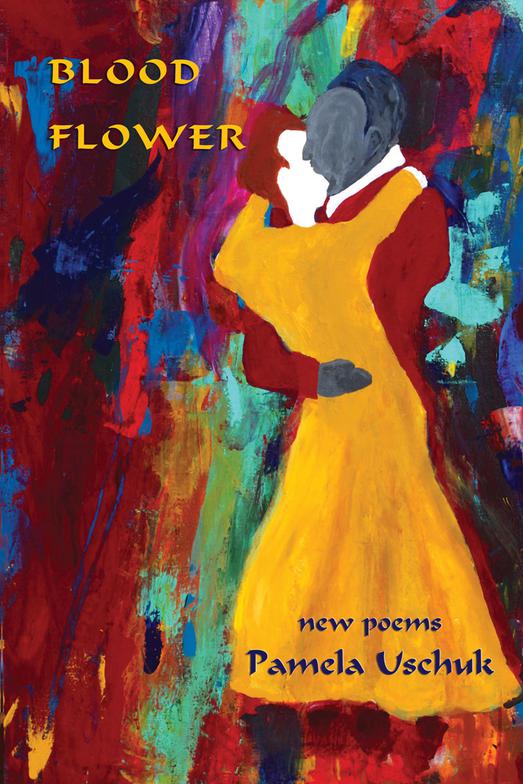

I interviewed distinguished American poet Pamela Uschuk, winner of numerous prizes including the War Poetry Prize, New Millenium Poetry Prize, Struga International Poetry Prize and the Dorothy Daniels Writing Award. In her latest collection, Blood Flower, Pamela writes about the startling, sometimes brutal stories of her Russian/Czech immigrant family and the long-term effects of war on combatants.

| ‘My concern with war is a theme throughout my life.’ | ‘I think in my family, I am the keeper and maker of the stories.’ |

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM ENDS

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM ENDS

A bluebird slips between electric wires,

and I remember waking to the radio static

of the Vice President

saying there was no choice but war,

but there were no plans for war, a confabulation

confusing as the tongue of a captive raven, split

so he’ll talk to amuse the neighbor

who nursed the raven back to health

after it was hit by a car in the street

and now keeps it caged in a backyard

where it has learned the price of being saved.

From ‘Blood Flower’

Leslie: Can you describe your style, influences and seminal works?

Pam: I don’t know if I can pin down a style. I write free verse poems laden with lush imagery, often a cascade of interwoven metaphors. My imagery draws heavily from the natural world. Birds show up, wild plants, trees walk through mountains and along rivers with no end. They illuminate content. The wild natural world informs me, balances me, grounds me. One of my intents as a poet is to create new ways of looking at metaphor in poetry. Because I hear music and have played musical instruments (the French horn, guitar, mandolin, and Native flute), my poems are sound rich with strong rhythms employing a great deal of syncopation, of internal and cross rhyme.

My intent is to make clear as much as possible the ineffable. Obfuscation does not interest me. Writing poems of substance that have meaning outside myself with the most craft I can muster is important to me. Often my poems touch on social issues, on human or animal rights issues. Justice and truth-telling concern me. My Russian/Czech ancestors with a literary tradition that uses strict versification and lush imagery has no doubt also influenced me.

My earliest influences were Theodore Roethke, TS Eliot, Jim Harrison, Richard Brautigan and Sylvia Plath. I adored Roethke’s metaphors, the way he explored the psyche by observing closely and interacting with the natural world. By exploring wild nature, its violence as well as its beauty, he explored the wilderness inside his psyche. Roethke’s “Meditations At Oyster Creek” and “In A Dark Time” were seminal poems for me. Roethke broke my heart and fired to almost a frenzy my young and passionate imagination. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” and “The Love Song Of J. Alfred Proofrock,” fascinated me as a freshman in high school. His language sent shivers down my spine. At that time, I shared his dismal speculations on the human condition.

As an undergraduate, I discovered Jim Harrison’s poems. I deeply admired the way Harrison would fuse Lorca-like imagery with a moon calf’s sentimentality and an acerbic tongue. His poems, like Roethke’s, were often grounded in natural imagery, and they often turned the tables on my expectations. Unlike Roethke, Harrison was completely irreverent. I was not drawn to Sylvia Plath as a tragic figure but I was taken with her as a superb craftswoman. Her imagery and use of language remain some of the most powerful of the 20th Century. At Interlochen Arts Academy I heard both Gary Snyder and Galway Kinnell read, and both those readings affected me greatly. I devoured Kinnell’s Book of Nightmares and still consider it one of the great book of poetry of the 20th Century. My next influence were writers from other cultures, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich and Native American writers like Joy Harjo, Linda Hogan and Luci Tapahonso.

Leslie: You describe your upbringing, speaking more than one language, as an experience that involved “facing mortality when we were little kids… playing war games.” How did your childhood set the pattern for the rest of your life? What has changed?

Pam: My beloved Czech grandmother spoke six languages fluently. In her house, my step-grandfather spoke Russian. My dad’s first language was Russian. Listening to all those languages created a rich tapestry of music in my young mind. My grandmother and I were extremely close, and I devoured her stories of the old country, of her coming to this country alone and knowing no English to be sold into slavery in a sweat shop. My grandmother ran away with the circus, where she met my Russian gangster grandfather who saw her singing and dancing there. I knew and still know her stories by heart.

I grew up on a farm in Michigan. My father was a WWII veteran, a decorated Air Corps tail gunner who fought in both theatres of that war. My brother and I often played war with my father’s helmet and mess kit and medals. We loved his many war stories. But, much of my father’s volatile temper was caused by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). My grandmother said that when my dad came back from the war, his eyes had changed, his eyes had hardened in a way that saddened her. Because he had seen so much destruction in the war, my father didn’t hunt like my friends’ fathers. He refused to shoot a deer. Being raised by a father I adored, but who was deeply scarred by war set a pattern, no doubt about that. When my brother went to the Vietnam War, he and I were pacifists. My brother came back a heroin addict and suffered greatly from PTSD all his adult life.

Too young, I married a Vietnam veteran, one of the three survivors of a massacred platoon of Marines in the TET Offensive. His PTSD was astonishing. He suffered from night terrors and often just screamed and screamed in the middle of the night. Our marriage came apart after less than two years. My concern with war is a theme throughout my life. My poems have explored PTSD in veterans as well as its effect on the women and children in their lives in fiction and in poetry. Knowing the vast repercussions of war’s destruction on a large scale both in combat, in communities and in the home, has led me to become an anti-war activist.

Leslie: You have a positive outlook on life. Where does that come from? What nurtures and what inhibits it?

Pam: Yes, mainly I’m an optimist. Perhaps that is because I’ve always maintained a close relationship with the natural world. I feel no separation from it. I’ve learned as much from animals, from forests, rivers, oceans and the shape-shifting sky as I have from my intellectual studies. I also know who my ancestors were and feel strongly connected to them through stories my grandma and father told me as I was growing up. I was proud of my Eastern European heritage. That created a stability in my spirit. And, I think I come by optimism naturally. Despite tragedies and tribulations, I’ve always been the half-full girl. My grandma said, “It’s always darkest before the dawn.” My dad chose to be positive and accepting at the end of his life while my mom was consumed by fear. By her example, I learned fear is a person’s most formidable enemy. One way to combat fear is with optimism and compassion. Both work for me.

Leslie: You played French horn and one of your poems is called ‘Shostakovich: Five Pieces’. What are the different types of music that inspire you and how have they shaped your life and writings?

Pam: Since I first heard it when I was a little girl, classical music has captured my heart. Maybe it was my dad playing classical music, Bach, Tchaikovsky and Beethoven, on Sunday mornings after a night of drinking too much beer. He and his buddies agreed it was the most effective hangover cure. Maybe it was my mom playing Rachmaninoff or the Polivetsian Dances on organ. Or maybe it was hearing classical music in my Grandma Anna’s house. Or maybe it came from playing classical pieces on the French horn in orchestra. Classical music speaks to me like no other music. As a teen, I loved the music of the 60s and 70s—the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival. And, I was smitten with some of the music my mom and dad listened to, especially Satchmo, Bessie Smith and Lady Day. My mom listened to music constantly throughout the day. Her radio was always on, and she sang along. She had a beautiful voice, and I loved listening to her.

Leslie: Can you expand on your idea in a lecture that “Crazy is good”?

Pam: By that I was referring to the poems in my collection, Crazy Love poems that address all the crazy loves in my life. I don’t mean that insanity is good. But being a little crazy, being willing to take risks other may consider crazy has served me well and led me to many adventures. For instance, my family thought I was crazy when at 27, I quit my tenured teaching job to become a writer. They also thought I was crazy to teach in a maximum security prison for men in upstate New York, but those “crazy” six years taught me much, including the vast difference between justice and the penal system, a corrupt national business that has very little to do with justice. Others thought I was crazy to drive across Montana over dangerous icy roads for years to teach poetry on Native American Reservations. Had I not done that I would not have learned about Indigenous peoples and their history that is not written in books. I would not have learned about the vast injustice perpetrated against them by our government and white culture. I would not have learned the kind of intuitive, healing and spiritual knowledge Indigenous people possess, far beyond any that we practice.

Pam: By that I was referring to the poems in my collection, Crazy Love poems that address all the crazy loves in my life. I don’t mean that insanity is good. But being a little crazy, being willing to take risks other may consider crazy has served me well and led me to many adventures. For instance, my family thought I was crazy when at 27, I quit my tenured teaching job to become a writer. They also thought I was crazy to teach in a maximum security prison for men in upstate New York, but those “crazy” six years taught me much, including the vast difference between justice and the penal system, a corrupt national business that has very little to do with justice. Others thought I was crazy to drive across Montana over dangerous icy roads for years to teach poetry on Native American Reservations. Had I not done that I would not have learned about Indigenous peoples and their history that is not written in books. I would not have learned about the vast injustice perpetrated against them by our government and white culture. I would not have learned the kind of intuitive, healing and spiritual knowledge Indigenous people possess, far beyond any that we practice.

Leslie: You say that during your illness you experienced “Chemo brain” and struggled to write one line a day. What was the core experience of having ovarian cancer? How has it changed you personally and as a writer?

Pam: This is a huge question, Leslie. Chemo brain is the term used to describe the side-effects of heavy-metal based chemotherapy that essentially bathes the brain for months in toxic and cell-killing chemicals. Mentation, rational judgment and memory are severely affected as are the emotions. I would often feel as it I’d had a lobotomy and find myself staring off into a distance I could barely translate. I would lose track of time, lying on the couch in a state of physical misery, of feeling very ill, headachy, nauseated, with severe bone and organ pain and wondering if I would survive. That long-term suffering made me very sensitive to the suffering of others. It was like looking at the night sky from a mountain top in the middle of the Alaskan wild. I keenly felt how insignificant I was, how utterly unimportant but also how I belonged to the great scheme of things, to the human race. I felt not one whit of superiority or vanity or ambition. I lived at survival level. That has changed me profoundly and never has really left me. I am extremely grateful for the way cancer has humbled me. I wake up every day and feel lucky to be alive, on this planet I love. Life is precious and nothing I take for granted. I hope it has helped me take better care of others in my life, to understand them, have more empathy and compassion and patience, something I often lacked before I had ovarian cancer.

Leslie: Why do you write?

Leslie: Why do you write?

Pam: I have to. When I don’t write, I feel ill. Writing is something I do because I am compelled to write. In every family, there is a singer, one who keeps the stories. I think in my family, I am the keeper and maker of the stories. I am the song maker. Because I am so passionately concerned with justice, my writing is also a sacred duty, to fight for justice. I give voice to those who have no voice of their own. It’s a honor and my charge. Nothing makes me feel more energized or alive than writing, than creating on the page. Imagine a painter who wasn’t allowed to pick up a brush or a musician who was forbidden to play an instrument. I can’t imagine not writing.

Next week, IZZY ROBERTSON, healer and author of four novels published by Magic Oxygen writes about love and how she explores that theme in her new novel Three Words.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

One Response

This is an interview that I need to read again as there is so much to take in. You have been through so much Pam but you are standing strong, like a beacon of light. I, like you feel that I have to write, it is like breathing but it is also incredibly healing. Thank you for baring your soul, for your honesty and courage. Blessings.