SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

I interviewed author Chitra Soundar about diversity in children’s writing and her own books. Chitra is an Indian-born British writer, based in London, who has an MA in Writing for Young People from Bath Spa University.

Chitra’s journey as a children’s author began early. As a lover of stories and a multi-linguist, she taught herself to read English by simply looking for hours at words and pictures; later she wrote songs for puppet shows for her Economics projects and won the Best Poetry Award in Junior College. As an undergraduate, Chitra’s essay on the state of education in India, written in Tamil, won the first prize in the all-state competition. Chitra says about herself today, “I fill my world with nephews, taking photos of flowers and birds, going to museums and attending dancing classes.”

Leslie: Can you tell the story, please, of your early experiments in a range of speech, reading and writing styles.

Chitra: I grew up reading, writing and listening to many languages. English came into my life early on and I also learnt Tamil, which is my mother-tongue, and Hindi – which is a language of the north of India. I read therefore literature from various sources – in Tamil most of my reading was what my parents were reading: magazines, jokes, short stories and newspapers. In English, because there weren’t many children’s books available locally, I read everything I could get my hands on – English readers with lots of short stories or abridged classics, Readers’ Digest, and some English magazines for kids – full of stories, poems and other things.

The local scene was more poetry and drama based. I watched a lot of stage plays – mostly comedies and listened to radio plays. All our popular music was from the movies and I was drawn towards the lyrics.

I graduated from children’s books to adult books when I was 14, but one thing I wasn’t introduced to formally and systematically was the classics. There was no one guiding my reading. I read voraciously and sometimes I regret not reading some great books during that time.

The internet hadn’t been invented until my generation passed out of university, so if our teachers and elders didn’t know what to recommend then we were on our own. Also libraries in schools and in the community were far and few to come by and, coming from a lower-income family, buying books in bookshops wasn’t really a choice I had. So my style evolved from my mongrel reading habits. I still prefer short stories – they were my favourites as a kid. I love to write poems and riddles. I love writing the twist-in-the-tale type of stories that were part of my Indian folklore diet.

Leslie: Is diversity natural to Indian culture? How do your books reflect that principle?

Chitra: India is big and diverse – whether it is language or clothes or religion. Literature has been more predictable though – there hasn’t been very much experimentation in short stories, novels or drama, so traditional literary fiction is the mainstay in both English and the vernacular. Poetry is the ultimate crown – those who can converse in couplets are revered.

I’m not sure if a book can be called diverse. I’m a writer made up of diverse atoms. Anything I write is through the lens of my upbringing, my education and my experience as a human being.

In Upside Down, a very simple story of not knowing more than you can see, the tortoise is panicked by the new world he sees. And perhaps many of us are like that today – the nationalistic tendencies that have arisen in India, UK and the US show us that we are not comfortable with the unfamiliar. We panic that the world has gone upside down. In the story, though, the tortoise has trusted friends who show him the right way. I can only hope in real life we all have friends who are brave enough to tell us when we’re wrong.

In the Prince Veera series books, the stories have been retold from the folklore of India – I have chosen stories that I grew up with – even though some were from the north and some were from the south of India. The stories are set in an imaginary kingdom – but I think they are somewhere in the North in my head.

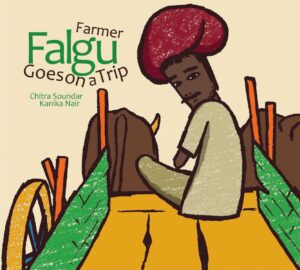

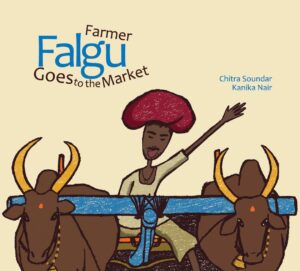

My Farmer Falgu series is a very good example of diverse India at its best. I wrote the story without actually imagining a farmer as he is now. The artwork was done by another South Indian Kanika Nair who was raised in the North – in Rajasthan. So she imagined the farmer to be a Rajasthani farmer. And the series has grown to four Farmer Falgu books, available across the world in many different languages – the story of a Rajasthani farmer from two south Indian creators published and loved by a south Indian publisher.

Leslie: When you write, where do your ideas come from? How do you develop them into finished pieces of writing?

Chitra: I used to focus on ideas from out there. Nowadays I look for ideas inward. I look for those emotions I carried as a child. And I find characters for stories inside me. Each story develops differently.

I’m most comfortable when writing a picture book. Usually I think in terms of scenes, a hook and a surprise ending. But most stories marinate in my brain and in my notebook for a long time. Some stories start out as something and I realise years later they actually mean something else. When that happens – when that realisation clicks, the story is easy to rewrite.

I’m more led by bursts of inspiration. Suddenly a character starts telling me the story and the words come. If I can get to a notebook or a computer quickly, I write it all down. A couple of chapters, 300 words and then it slows down. Then I look at it more pragmatically and wonder if it was just a burst or does it have the stamina to hold a story together.

The one thing I’m putting more conscious effort into is being unconscious about ideas, about letting the subconscious take over. Life gets in the way often and I’m finding it less and less easy to keep it all in the head – I have to scribble, write phrases, draw stick pictures before my ideas can take shape.

Leslie: Where do you go for help as a writer? What kind of personal support/critique works best for you?

Chitra: I’m part of a couple of critique groups that were informally organised. I used to be part of an online critique group organised by the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators for their members.

I prefer to get and give structural critiques – more the big picture of the story, the plot, the character’s motivation, whether the story hangs together. The thing with critique groups is that you need trust – trust that your critique group partners will respect the writing, and will critique the story in front of you – not the person. You also need to trust that they are looking out for you and want the best for you. If the trust is not there or lost, then the process doesn’t work.

I also enjoy working with other writers who want help – especially on their picture book manuscripts. I love editing mine and other people’s work.

When I’m stuck or unsure of the trajectory of my story, I seek out friends whom I trust, who are experienced in the art of longer fiction.

A good critique group is worth its weight in gold and diamonds.

Leslie: Who are the authors and other thinkers who have influenced you – why them?

Chitra: As a child, I read more British authors than Indian – but I did read a few Indian writers who were publishing for children.

I read a lot of biographies as a teenager – Lee Iacocca to Gandhi – I still love reading memoirs and biographies that teach life’s wisdom through someone’s life experience. I’m deeply moved by Buddhist and Hindu teachings, folk wisdom of India and stories handed down from generation to generation.

From every person I meet, I try and pick up one good habit. One thing that I could do better. But it is hard to pin down a few specific influences as I am still being influenced every day – I’m equally moved by the Dalai Lama, the current Pope – Pope Francis, the Obamas, Steve Jobs and Malala Yousafzai.

Leslie: You are interested in diversity in children’s writing in English. What are your conclusions from the surveys you’ve conducted so far and your own observations?

Chitra: In spite of the current political rhetoric, the US publishing sector has a better track record of diversity in children’s publishing than the UK. I tried to trace back diversity to times when Britain was an empire and, guess what, they didn’t think it was necessary even then.

As an aunt of mixed-race kids, and as a writer visiting far-flung schools, I’m really disappointed by the unavailability of diverse books for children of all ages – the younger the age, less the diversity. Adult publishing is doing way better than children’s in that regard. And if they are available, they are tokens – and the same set of books go round and round schools and libraries. There is far too little done to improve the discoverability of books that are being published by houses that are committed to it.

I’ve been in discussions with industry experts and it is a common feeling that the distribution network lacks the diverse staff with the necessary skills and knowledge to market to a wider demographic. So the standard excuse that ‘diverse books don’t sell’ is already established before books are rejected.

Also one or two big successes in the young adult market – the recent Waterstones prizes, the NY Times bestselling books by Angie Thomas and Nicola Yoon have given an illusion that we are fine – we don’t have a problem in representation.

Cultural representation aside, ability, gender and LGBTQ readers and families are not served very well either. Imagine a child who can’t really join in sports and wants to read a story – and the parents can’t find fun, accessible and mainstream stories featuring a similar child – there is a danger of demotivating that child for life. Imagine not being able to see two mums or two dads in a family, or a happy single parent family – a child in such a family is going to feel left out of society.

There is a lot to be done – a lot more which doesn’t necessarily include diversity panels, which can be part of the talk about diversity designed to create an impression of action. However, recent announcements from Hachette and Penguin Random House about tracking their diversity performance are a welcome move. If the publishing value chain is diverse, then its output will be too. Until then, we take small steps on a long road.

Leslie: Can you describe the personal meaning, please, behind your quote: ‘Fiction is reality & vice versa. Imagination is the only way we can reach depths of who we are physically & otherwise’?

Chitra: Fiction is an exploration of the self. Whether it is something I write or read. If I am reading, the writer’s words complete in my mind I bring my own experiences to the words and feel what I feel. Which is why some people love a book while others are indifferent.

As a kid I always used the book as a “what-if” scenario. What would I do if I were in the same situation – whether it is Nancy Drew jumping over the fence to catch a thief or the Famous Five stuck when the tides come in (mind you I had no idea what a cove was or how they were affected by tides, neither did I know what scones were).

Fiction cannot exist in isolation. It is a manifestation of what we see out there and an extension of that reality through imagination. But the imagination itself has a lens – the lens of each writer’s experience in the world, their upbringing, their education, their philosophy of life. Even when we are writing dystopian or futuristic fiction, we are writing about how life is here and now.

Often things writers imagine come true – be it scientific advancements like the satellite dreamed up by Arthur C Clarke or dystopian, fake-news-dominated tyrant governments.

As a child reader, life experience is limited and set in certain ways based on the adults in the reader’s life. To these readers, books open up the world. If children find themselves always in a world where a certain truth is reinforced, then in reality, that reader grows up to believe that is his reality.

If we introduce our children to books from across the world, showing them experiences of a child in a paddy field to an inventor boy in Africa who prevents lions from attacking his farm, then the reader’s view is expanded more than her or his experience. Books bring the world to that cosy blanket fort where everyone learns to imagine going to space, becoming a fireman or aboard a pirate ship. Who knows maybe that imagination will inspire the child to become the astronaut he always imagined herself to be or turn into an inventor just like the African boy she read about.

Leslie: Is there an element of self-exploration in writing for and about children? If so, what does it uncover in you?

Chitra: I think all writing is self-exploration. When writing for children, it is more in primary colours – happy or not, angry or annoyed. I don’t think I grew up emotionally much – I alternate between a 7-year old self and a very timid teenager.

But to write for the younger age-group, it’s important to wear a different lens. That’s the challenge – how do you unlearn everything you learnt as an adult and think about this world as a seven year old or less and find those emotions you would feel in today’s world. Looking at the world from a different height, a different emotional state and from the naïve hope of a young person who always believes they can change the world is a privilege. Adults tend to become cynical and give up on clearing plastic from the oceans or saving the slug on the street, but kids don’t.

I’ve become more playful, more positive and less serious about life ever since I embraced what it means to be writing for children. And actually more than writing, performing my writing, telling the stories orally, brought back the joy of being that child when I was that age. Now I’m an adult only when I need to be – that sure does frustrate many people, especially my tax accountant, but that has made me more cheerful and less worried about tomorrow. I used to be a careful person and now I’m more open to walking into tomorrow without a plan whatever it brings.

Next week I interview Lyanne Thornton-Harewood of May Contain Nuts, a theatre company who deal mainly with mental health issues, challenging the stigma that surrounds the subject.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |