SELF-HELP AND RESILIENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

I interviewed Bertin Kalimbiro from the Democratic Republic of Congo about his work in the Goma region to grow food safely and help people threatened

During childhood, Beth, my protagonist in my most recent novel ‘Violet’, pins up these sayings on her bedroom door:

During childhood, Beth, my protagonist in my most recent novel ‘Violet’, pins up these sayings on her bedroom door:

Their source is Beth’s gran ‘…a big-jawed woman whose sepia-tinted photo stood on the cabinet beside Beth’s bed’. But Beth, when asked by her dad (perhaps disingenuously) where they came from doesn’t want to tell. Already she’s a student of life, quoting her gran about the importance of books, but when it comes to her ‘sayings’ she wants to share them but not their source.

Their source is Beth’s gran ‘…a big-jawed woman whose sepia-tinted photo stood on the cabinet beside Beth’s bed’. But Beth, when asked by her dad (perhaps disingenuously) where they came from doesn’t want to tell. Already she’s a student of life, quoting her gran about the importance of books, but when it comes to her ‘sayings’ she wants to share them but not their source.

Perhaps she’s shielding her grandmother’s memory or needs to impress, but whatever the reason, there’s a gesture involved, a kind of magical defiance of limits and boundaries – and this is the beginning of Beth the Storyteller.

So the scene continues:

When asked where they came from, she coloured slightly. When pressed by her dad, she smiled. “It’s what we think,” she said, inviting him to view them. “All of us,” she went on, standing at the bed end. The pronoun included herself and John, her mother, her brother, even old Jim, but most of all the image of her now-deceased grandmother. “She wrote because of you,” her dad said another time, pointing to the photo. Beth fell silent as she looked. The long-faced woman was standing tall, with swept back hair and a thoughtful expression. Framed by a window, she was gazing out on an overgrown garden. “It was her gift,” added John. His daughter nodded. Her white-faced gran belonged, it seemed, to one of Beth’s own stories: tales of daring and one-time adventures which she’d written in her sketchbooks then back-flipped and spread to begin a new story. And as Beth grew older she voiced her tales, setting them outdoors. Under her direction, with herself as protagonist and featuring her brother, she plotted and scripted and staged them in the garden. “Toby,” she called, “this part’s for you.” And if he didn’t want it or walked off to a corner, she simply delivered solo then started something else. Because outdoors she could do anything. As Beth she was half-lady, half-outlaw, switching between stories and mixing genre. Her parents didn’t know it, but she’d horses and spacesuits and teacups and binoculars that she air-drew and named, directing their use as prompts in her story. The main game was Shipwreck, with Captain Beth, standing on the rockery, sighting dolphins and navigating channels as she directed forward. “Land ahoy!” she called and Toby echoed, leaning into the wind. As the waves became taller they swayed side to side and mimed their parts, shouting. When the water took over they ran downhill, taking to the lifeboats. “Abandon ship!” she shouted. Reaching her boat, Beth began air-rowing, advancing at a crouch. “We’re washed up!” she called when she arrived at the lawn. Toby joined her saying nothing. Without even noticing he’d walked untouched across a wide stretch of path. In the story this was water. “Toby!” she cried, pointing. “You drowned.” The boy flushed. “You can’t do that.” “Can.” “Well, you shouldn’t.” The boy stepped back, planting both feet on the path. “You’re spoiling.” “No.” “I’m the captain and I say so.” Eyes down, Toby returned to the lawn. Beth sighed. “Now we’ll explore inland,” she said, leading down-lawn to a dogleg at the back. Toby followed in silence. Here they took shelter beneath some overhanging branches. Screened by leaves they peered across grass. Blackbirds and finches were hopping around the edges. “It’s an island,” she called, “with treasure and wild animals.” The patch beyond was damp and leafy and spread with growth. There were fruit trees and climbers, weeds under bushes and mildewed roses. Toby blinked. “And that’s HQ,” he announced, pointing upwards. In the tree above, a series of ladders with halfway landings led to a wood-and-canvas platform. Beth shook her head, “It’s the Wendy House, where the castaways live.” The boy made himself busy. He was jerking at a branch. “So now,” she added, approaching the ladder, “we’re the lost boys. Which means, yes, we can fly...” Beth back-swung and began to climb. With a springy, bunched-up movement, Toby followed. They clambered up to a flat run of boards divided by a wooden partition. There were support struts both sides, a door between, and a grey, stretchy, holed-through canvas roof. It looked like a cross between a hut and a tent. Ducking forward they passed through the door. Inside was messy. In the centre was a bamboo table covered with flaking chalks, two battered slates and a blue plastic tea set. Beads on strings hung down from the sides. Two orange box seats were stacked underneath. Beth pulled out a crate then picked up a pole from the floor. Mounting the crate, she applied the pole end to her eye, turning a circle. “Nothing on the horizon,” she said, expressionless. “Or on the island,” she added, swinging round. At the table, Toby was spot-testing chalks, breaking them in half and scrubbing the ends, before drawing. Beth continued scanning then dropped her head. Toby had completed a scrawly, pear-shaped outline with shaded-in areas. “It’s a map,” he mumbled when questioned from above. “That’s where we are?” Toby continued drawing. “Of course, it’s a story,” she said slowly. “And this is how it goes...” Speaking quietly, as if from memory, Beth began. Directing her voice, she named her characters as Beth and Toby and described a shipwreck with the girl rowing clear and the boy treading water. The Wendy House followed, with treasure and wild animals. Next was their landing, the move inland, an island tree house – her lookout, his HQ – leading to a bamboo table with chalks and crates. Here her expression softened as she spoke about the place, the castaways together, mentioning the boy, the maps, the girl as captain, who made it all happen... “And that’s their story,” she ended with a lilt. “And as long as they keep telling it, they’ll never leave the island.”

In writing this I had to find a way to move from Beth’s memories of her gran to the children in action – and to do it smoothly, without the reader noticing. After many attempts, the link I wanted came with the phrase ‘voiced her tales’. It was short, sounded natural, and gave me something to hold onto while I switched direction.

But scene changes don’t always come so tightly-worded. Quite often I try the slow blend, adding in words to smooth the way or I’ll bring in someone talking. But if it’s a big jump I’ll use the line break or start a new chapter. Even so, standard transitions are hard. Too much explanation and the writing stalls, too little lead-in and it ends up feeling forced.

On the other hand, if the transition’s good and gives back in itself then the novel is lifted, taking on a quality where things just happen. The goal is immersion. A kind of seamless, dream-like progression where everything fits, the feelings stand out and there are no skipped pages.

If anything, that’s even harder.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Bertin Kalimbiro from the Democratic Republic of Congo about his work in the Goma region to grow food safely and help people threatened

I interviewed computer expert and sustainability campaigner Dr Erlijn van Genuchten, who writes easy-to-understand books based on science full of practical suggestions for planet-friendly living.

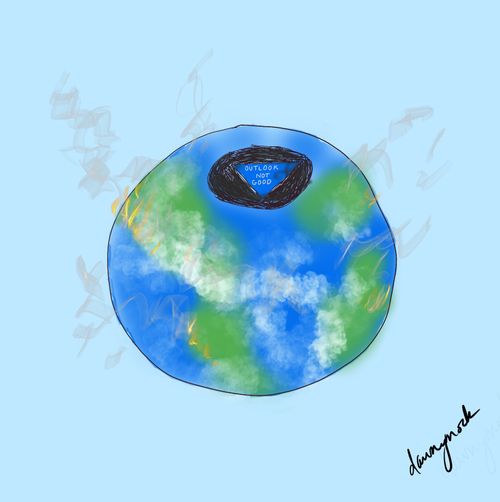

I interviewed Canadian cartoonist Dawn Mockler about how she works on cartoons that might be environmental or wordless but always witty – especially her famous

I inteviewed Helen M Stevens about how she has revived the art of embroidery, creating original contemporary patterns while studying and drawing on, “One of

I interviewed Councillor Rachel Smith-Lyte about the origins of her passion for nature and her environmental activism. Rachel tells the story of her teaching (and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Succinct, considered analysis of the craft. Helpful. reassuring tips for writers. It is reassuring to read about the energy invested in the words choices.

Thanks, Jessie – you get everywhere! Yes, every word in a piece of writing is a choice and put there for a purpose. 🙂 🙂 🙂