JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

Skyscrapers are not raised simply to conceal dead mice – Saul Bellow.

I find that the best writing comes out of the dark. Often it starts from a single word, a thought or an incident that sets off a search – which I’m experiencing now, writing this blog – involving lots of stops and false starts.

While I’m searching I try out phrases and listen to how the words sound, judging their effect on the reader. I’m also editing every sentence as I go, juggling the phrases to achieve the most elegant formulation and removing words that overburden it. At the same time I’m plugging gaps, enhancing effects and reading back to ensure continuity. In addition, and crucially, I’m writing for feel, mood and flow, visualising the incidents and riding the emotional waves as I go.

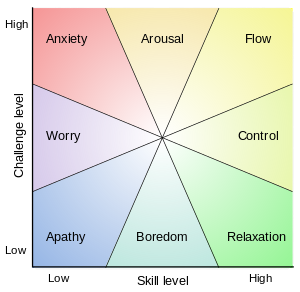

I draw on long-term schemas when I’m writing. So I’ve thought through my most important life experiences, tracing their patterns and bundling them into meaningful wholes. Usually it’s the painful moments that count – the confusions of youth, the breakdown of relationships and hidden dreams and losses. But the writing mustn’t be too pumped-up. The feelings may spark but the heat they generate has to be contained. In fact when I reach a climax I don’t experience it directly, I just watch it develop. I think of this phase as cold fire. It’s a dream move, rather like the runner’s experience when the body takes over. It’s been described in various fields of activity as being ‘wired in’, ‘in the zone’ or ‘playing the A-game’. And the more skill you have, through keeping in practice and setting the right goals, the easier the flow…

That’s when writing comes easiest, but it has to be steered or ridden as it goes its own way. Shaping is all. There isn’t a route one and it can’t be reduced to a formula. Most of all, it takes skill, care over details and repeated attempts. As Saul Bellow said about the novel: “Skyscrapers are not raised simply to conceal dead mice.” So it’s not quick, it’s not therapy and it isn’t a trick.

Saul Bellow’s remark has that doubleness of meaning which characterises great quotes. He could be rejecting the Freudian theory of art as a defence mechanism against neurosis or he could be criticising whodunnits. Both see art as a concealment process. So the reader’s job is to break the code, guess the hidden secret and ‘explain’ the story. It’s like trying out a bunch of keys in a door knowing there’s only one that fits. Sometimes there are a number of possible readings, but it’s still rather different to open-ended fiction. In this kind of book it’s important to give nothing away and avoid too much elaboration. Paradoxically, this flat, stripped-down style invites the reader to see through to the artificial nature of the writing. Some post-modern thinkers praise this approach which allows, they say, a ‘democratic’ space where the reader is at the centre of the action, trying to guess Quo Vadis? or What Would You Do If This Happened To You? Often these plot-twists have a ‘gaming’ aspect to them, relying heavily on shock tactics drawn from mixed conventions and genres. So everything is in flux and the author simply shuffles the cards. It’s clever, value-free and against ‘closure’. Most of all, it claims to deconstruct elitist culture – though the theories of postmodernism are expressed in a rarefied code exclusive to those in the know.

What postmoderns call ‘transparency’ can be an excuse to write conventional stories that manipulate ideas but fail to create rounded characters. The result, in some cases, is thin writing where the sketch is valued above the finished work and minor characters take over the role of protagonists. As Kurt Vonnegut said: “Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such a complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.”

Another take on writing is the jigsaw metaphor. In this the writer moves around chunks of story, or strips of language, fitting them together according to traditional patterns. It’s rather Platonic and beautiful, often minimalist, and moves us in familiar ways. Sometimes called ‘classic’, it assumes that there is a correct formulation the writer is trying to find. For me, this is a traditional route which gives direction but can also present false trails and walled-in gardens where the real and current life never gets a look-in. Its pleasing symmetry can divert from the real task, which is to peer into the unknown.

Writing, for me, is like wriggling into a hiding place through a narrow entrance. It reminds me of entering the hollowed-out space I discovered beneath the hedge as a child. There I could watch the world through a leaf screen, filtering experience while looking out for new developments. Although it felt special in my own secret hideout, I was also alone and rather cut off. The hedge was a raw, spiky barrier but also a peephole, transforming perception so everything was seen from ‘the other side’.

To write is a shot in the dark. The flow of language isn’t always there. At times it’s a radio in the head, a fitful collection of words and half-tunes which stop and start and come and go like the sound of a distant event carried on the breeze. Sometimes it’s close-up and insistent but at other times it pulls away, becoming garbled and clichéd. And it’s in need of constant adjustment as it drifts off the station, becoming muddy or confused.

There are other metaphors, too. Writing can be a show garden where the styles run together in a carefully-planted mixture of formal and wild. Or it can be an archaeological dig where the finds are fitted together imaginatively to conjure up another time and place.

More prosaically, writing can be a sorting exercise, combining Cinderella’s task of separating the good from the bad lentils with a game of Pairs. So when I find that a subject brings with it a whole, fully-formed vocabulary, I write the words down in lists and keep trying out different combinations, hoping to find a fit. When I’m full of phrases like this I see it as a good sign and believe that I’ll complete my daily word quota without too much effort. Unfortunately, a mechanical approach usually leads to a dead end where it’s never quite there. So by the end of the day I find myself unsuccessfully repeating phrases I’ve tried and rejected to see if I’ve ‘heard them right’.

It’s this sounding out process against the inner ear which ultimately decides the flow of a written piece. Words fit together or they don’t according to their music, and the detailed edit that attempts to adjust them to a clear logical order and ‘reader-friendly’ format has to be just that – a secondary elaboration. Sound is sense is story. To settle for less is to ignore the voice in the ear, warning against safe, well-crafted, middle-of-the-road writing which aims to do no more than put on a game show for passing entertainment. I prefer the writing that allows for ambiguity and character development, which isn’t contained within a style box, where the meaning develops from imagery and register, and the words shine a light into the contradictions of the human heart.

At the end of writing this blog I have a long tail of unused sentences. They are the background voices that didn’t quite make it but add in colour, light and shade. Without them I couldn’t have written anything.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

3 responses

Wow, I kind of just blunder around until something ‘pops’ 🙂

Ah, after reading what you said a few times I realised that you’re not describing the effect of reading the blog (thank goodness). What you’re describing is your process as a writer. My wife Sue Hampton is more instinctive like that. I think there may be two types of author, dominated by head or heart…

This is a fascinating post and beautifully written – I’m working with an author mentor on my second novel (paid for by the wonderful Scottish Book Trust) and she set me to reading Story by Robert McKee to help with structure, it has been a revelation.