JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed novelist and academic Mehreen Ahmed about her stream of consciousness fiction, her five published novels, and the personal methods and experiences that underpin her Modernist writing. Mehreen, who is an expert in computer-assisted language learning, has published several papers on the subject and has been successful in a number of writing prizes. She also has two MAs and comes from a family of writers. Born in Bangladesh, she now lives in Brisbane, Australia.

Leslie: I know that being a child refugee is one of your most powerful formative experiences. Could tell me your story, please?

Mehreen: A civil war broke out between Pakistan and present-day Bangladesh in 1971. I didn’t understand the manifold reasons for the war then as well as I understand them now. But my father was a high official, a general manager of a Jute Mill called ‘The Platinum Jute Mills’, in the district of Khulna, Bangladesh. We lived in a huge bungalow on an acreage overlooking the Bhairab river. Life was pleasant and calm, living in the luxury of natural beauty.

Then one day, my father came home early and I overheard him ask my mother to pack a small suitcase. We needed to get across the river to safety, he said, because the mill was under attack from the Pakistani army and there was no telling what they might do. I remember my mother quickly packing a small suitcase… but then my memories seem to change, becoming present tense, as if everything was happening now…

Leslie: Please go on.

Mehreen: Before I can find my bearings, our bungalow is full of officers and staff working in the mill with their families. We are gathered in the front lawn, under the leadership of my father. We do what he tells us to do. We walk down to one of our many jetties of the mill and wait there while people organise boats. Boatmen are only too happy to take us across the river where the military will not find us in the safety of the villages. Once across, a village farmer welcomes all of us with open arms. He feeds us rice and dhal. So many of us too! But his incredible generosity teaches me about goodness in human nature.

Later that night I cannot sleep. So I walk outside under a starry peaceful night. I find myself on the edge of a pond. I hear people whispering and then a see a long, sharp butcher’s knife in somebody’s hand shinning under the moon light. I am scared. I flee to my mother. She tells me that we must get a good sleep because we are heading toward the capital city Dhaka the next morning. This place is not secure anymore, she says. At seven years of age, I can’t figure out much at all.

Leslie: And the next morning?

Mehreen: The next day is another toilsome long journey on foot. We meet a lot of people on the road who my father thinks are informers and military spies. In the meantime we also hear on the radio that some people are carrying guns in their hands that the freedom fighters are gaining strength in guerrilla warfare with the assistance of India. I am not sure yet what to feel, happy or sad, because I am just too tired and ready to drop anytime. It’s a marathon walk to the river bank from which we are expected to take an engine boat or launch. We continue our walk in fear. People whisper amongst themselves that women, girls as young as 10 or 12 have been taken from various villages to the pleasure houses of the Pakistan army. My mother, a pretty young lady, is just as concerned about me as my father is about her.

We finally reach the river banks and again an owner of a launch generously welcomes us. In a while the launch sets sail. I eat dry rice and molasses, just one meal a day. I sit near the porthole and watch the river. But there is no beauty in its folds today, only swollen decapitated bodies floating downstream.

It takes us about seven days to get to Dhaka. Many of our fellow officers and travellers have now gone to India. And we are headed to our grandmother’s house in an auto rickshaw. There is panic in the roads. The roads are nearly empty. The driver tells us on the way about the brutality of the army, the horrific genocide. How they have already killed millions of people, poor villagers, rickshaw wallahs. They have also killed many intellectuals and university professors. My father’s life is in danger too. Next the military will come for the professionals like him. He must go into hiding. We reach our grandmother’s house. But my father cannot stay here. It is dangerous because it is too close to a military headquarters. We get separated. I still remember the fear that I may lose him…

Leslie: Go on, please.

Mehreen: We continue to live in my grandmother’s house for a long time. We have no clothes on us, only rags. For the first few months we wear clothes handed out to us by my cousins. We have no money at this stage, because my father cannot go to the bank. Whatever cash there is must be saved and spent wisely. I am not allowed to go out for fear that the military may pick me up. At night we keep awake hearing shrieking voices crying, “Help me, help me!” from our neighbours’ houses. Young girls are being picked up almost every day. I shut my eyes. I pray. Will God listen to my prayers in the silence of this dark room as I lie there with my grandparents? My mother’s sleeping in another room. We hear gunfire every day. We hide under the staircase when the sirens for bombing go off. We hear that this suburb can be flattened to the ground any day if the USA 7th fleet waiting not too far away on the bay of Bengal, comes to the aid of the military.

Panic seizes us as we wait for a resolution. There is none. In the meantime, the ration for daily meals get smaller by the day. My granddad, needs regular medicine for his diabetes. Mum has to go out, taking huge risks, to the drug stores to get it. Nine long months pass like this. And then suddenly we hear that the army has surrendered to the Indian army. The victory is ours!

Leslie: That’s a life-changing experience. Thank you. As you grew older, what other experiences contributed to you becoming a writer?

Mehreen: After the war we settled down into a more normal existence. I have always been a keen reader and a keen observer of nature. I wouldn’t say my interest in nature was as profound as the romantics perhaps, particularly Wordsworth who saw the soul of God in nature. But I have always been drawn towards, trees, hills, oceans, sunsets and sunrises. I would often jot down my observations and my feelings in a diary. I think my love for nature has helped me to become a humanist in the end, which I try to mirror in my books.

Leslie: What are the particular personal passions/experiences that you’ve either adapted as episodes into your books or secretly underpin the emotions you portray in your books?

Mehreen: Nearly all of my books are depictions of strong humanistic values. I uphold human conditions more so than writing in a genre such as, say, romance or adventure or thriller. My books are not a medium to express my personal feelings or experiences, but rather a platform to encourage a societal and political change. In a way, I see myself more of an activist, I think. I cannot stand wars, poverty, child molestations, human suffering and so on. I think that feeling is driven by my early experience of being a war refugee. In my depiction of reality, I often portray such situations in my books, speaking at length about refugees, child abuse and sufferings.

Leslie: What are your daily writing routines? What helps and hinders you to come up with your best writing?

Mehreen: I am not very structured. And I also don’t write on a regular basis. I write when I am inspired by something. I’ve noticed that nature plays a great role here. Rain inspires me to a great extend; a visit to the beach will inspire me. What impedes my writing most is when I am depressed for some reason. I just can’t get my pen to move at all. I think I have to be relatively at peace. Chaos and confusion do not create the perfect condition for me to write.

Leslie What part does daily observation play in building up a novel? e.g. notebooks, camera, journal, sketch book and/or visits to places etc

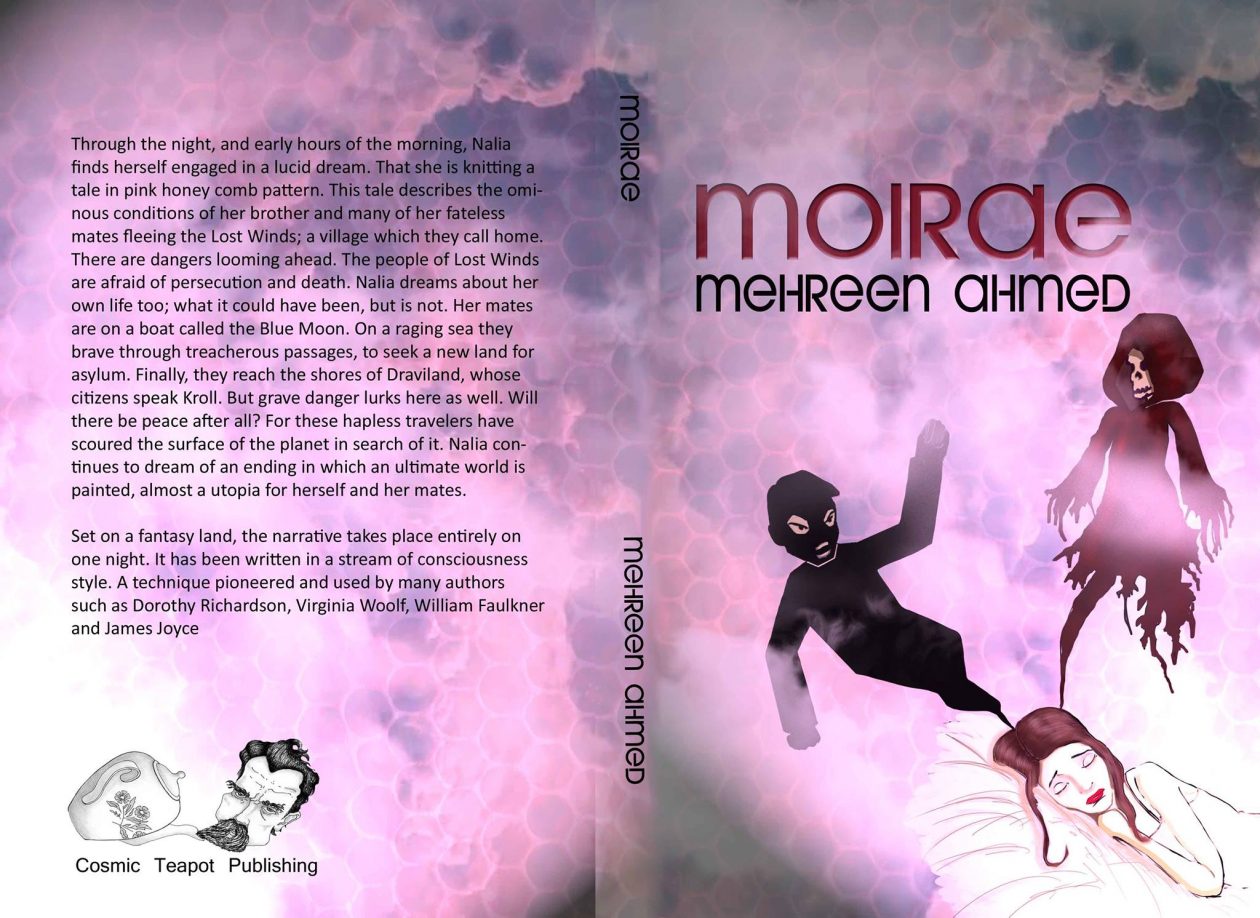

Mehreen: Journal and visits to places particularly, to the mountains, sea beaches and so on. My book, The Pacifist, and Moirae, both have references to the sea. Natural surroundings help me to find a deeper meaning in life somewhat; they provide the conditions for tranquillity.

Leslie: Can you describe, please, the progress of your writing from first novel, through other novels and short stories up to your latest book Moirae. What were the milestones/turning points and key insights on the way? Which is your best book, and why?

Mehreen: My first book was a novella, Jacaranda Blues, which I wrote in a stream of consciousness style. I found myself easily drawn toward this style of writing. I never learnt it. It came naturally to me. Then I wrote a collection of short stories. And then Moirae, an ode to a nondescript floating population which the world had chosen to forget. There was a time, when I used to see a lot of refugees on television, people trying to flee by boat for various reasons. They just couldn’t continue to live their lives in their own countries any more. Fear of death and persecution for religious reasons or political was so grave, that they became refugees. No country would take them either, because the vetting system was so rigorous that they would almost always not meet the criteria for refugees.

I felt their pain. My empathy for them was so great that I could envisage this chaos and confusion of their minds. I chose this style, because I thought this would best capture the raw emotions.

Moirae is an allegory of an absurd world or situation if you like in which people are caught in uncertain limbo for years. A story conceived in a dream, although it is not clear from reading the book that the character is dreaming because often the dreamer doesn’t know that. The dreamer only knows upon waking. And that’s the impression I tried to create in the book.

The character is not the narrator. Rather the narrator reads the mind of the dreamer, and streamlines her own point of view into the character’s dreams like waves crashing into one another without boundaries, thoughts without borders. And part of that mix involves the author using the most suitable syntax, not the most sophisticated one, to truthfully represent the dreamer/character’s thoughts.

Leslie: Who have been the people who influenced you the most – why them?

Mehreen: Apart from the academic influences, my family has also had a great effect on me. I come from a liberal family where kindness was predominant. I grew up under the influence of two voracious readers, my mum and my dad. I heard talks about egalitarianism and eradication of poverty ever since I learnt to understand. I think these have played a major role in my formative years.

Leslie: You’re a stream of consciousness writer. What are the different ways Conrad, Joyce and Virginia Woolf practise this technique?

Mehreen: I would say, Woolf displays more adherence to grammar than Joyce and Conrad. For her it is more a matter of thoughts losing coherence but still within grammatical principles. But for Joyce and Conrad, I think it is more a matter of what’s in the heads of the characters, rather than the technicality. In the end, they are all great expressions of literary techniques.

Adherence to grammar or norm doesn’t necessarily make the perfect art form, but rather how realistically those thoughts are portrayed. In my view, I like to work with raw thoughts and raw emotions and portray them in their inherent ‘rawness’. Therefore, stream-of-consciousness is the best artistic device for me.

Leslie: How did you learn to write stream of consciousness, what stylistic mannerism characterise your particular way of writing it, and why did you choose this technique for the subjects you write about?

Mehreen: My debut was Jacaranda Blues, which I started to write almost involuntarily in a stream-of-consciousness style of writing. I was drawn towards the character’s thoughts. I didn’t learn it. It came to me.

A non-adherence to grammar would characterise my style. Because I deal with the ‘rawness’ essentially, I find this is the most realistic and natural way to present my characters’ thoughts which are vastly incoherent, not contained within any parametric boundary.

Leslie: What is your responsibility as an author to your reader? How do you justify your language techniques you use that might make your text “harder” to understand?

Mehreen: I think it all comes down to the writer’s belief that what they do has to be in the best interest of their subject. To find the right format to portray reality, as they think is fit. Readers and writers don’t always match where tastes are concerned. But many readers actually like this style although they may find it, ‘hard’. The poetic passages and the sincerity of the narrative compensate for difficult reading.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

Mehreen had a very traumatic youth. An experience like that would definitely have a big impact on the kind of person you become later in life. A fascinating read.

Yes indeed. I’m glad you enjoyed it. 🙂 🙂 🙂

An amazing woman, to survive the horrors. A wonderful piece thank you.

🙂 🙂 🙂