JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

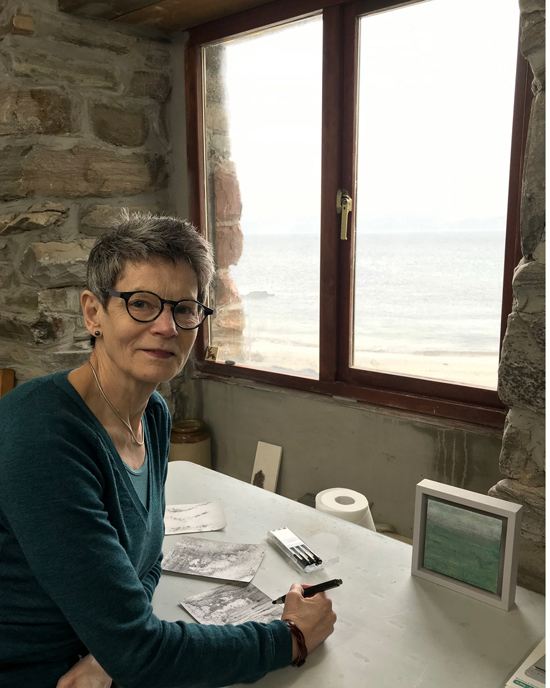

I interviewed Jane Rushton, an artist whose Scottish and Arctic landscapes capture a deep and subtle sense of innerness. I asked her about her trips to Greenland and Svalbard, her relationship to maps, geology and atmospheric scientists as well as to climate change. Jane also talked in depth about her ‘slow art’ and unique compositional methods.

Leslie: How has working as an artist in the Arctic regions changed you and your expressive work?

Jane: The Northern focus in my work reflects where I feel the greatest sense of belonging and resonance, and this is in terms of landscape, light, weather, sense of place and space. I am drawn to quiet, apparently empty places and I think that is because one has to slow down and be open and receptive in order to really connect with what is there.

My first Arctic trip was to Greenland in the summer of 2000 and it had a profound effect on me. Travelling across the tundra carrying only what was needed for basic survival (including sketchbook and minimal materials), and seeing no-one other than my partner, was probably the first time I felt truly alive and connected to my environment. My emotions ranged from sheer joy to fear, despair and pain, with periods of calm, wonder and meditation in between. I felt and still feel utterly privileged to have had this experience as it provoked a deeper awareness of interconnectedness – a notion that I talk about later in the interview.

The act of walking became integral to the creative process; the rhythm of the breath and the pace of the step triggered a contemplative state in which all of the senses were fully tuned in, which in turn became a catalyst for personal and creative development.

It is strange, but at first I felt that I was in a landscape that, while being undoubtedly wild and beautiful, felt sparse and empty for me as an artist. It took about two days for my eye and my mind to start becoming attuned to the richness that was there, and it was astonishing.

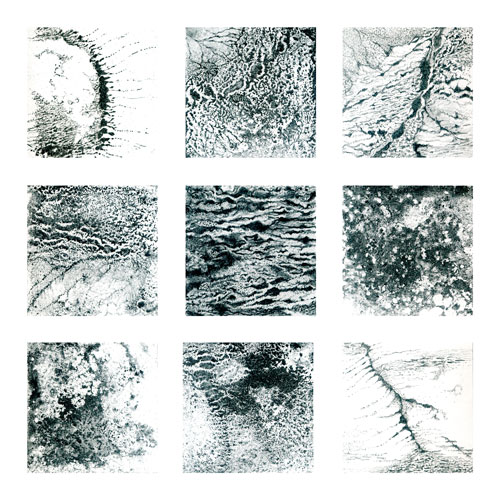

A lot of the work I’ve made about that and subsequent Greenland trips attends to the notions of distance and proximity. One’s eye and mind seem to be either somewhere in the vast distance, or in close scrutiny. In slowing down and just being with the landscape the attention is caught by the smallest of things and the most tentative of relationships – from the structures visible within the various rock types and the palimpsest of lichen colony growth, to the push and pull of plants of the tundra carpet.

Walking through the low scrub of the tundra was a multi-sensory experience: the smell of the Ledum (Labrador Tea) caught underfoot was constantly present, the sound of the great Northern Diver with its otherworldly evening call, the sensing of a reindeer passing the tent, or an arctic fox on the lookout for scraps, the feel of the rock under ones fingers, and the delicate, yet resilient arctic flowers.

Back in 2000 the effects of climate change were being noted in the arctic, with rising temperatures and receding glaciers, but it wasn’t in the public consciousness in the way it is now. My subsequent journeys north have actively confirmed to me that things are changing fast, and this is borne out, not only by science, but also in the testimonies of Greenlandic friends whose lifestyles have to adapt.

I see my work relating to the arctic as a way of engaging the viewer in looking, thinking and valuing. If that then encourages an engagement with valuing our environment I am happy. I don’t feel it is my artistic place to make political comment – it is my place to make art. For me, politics and art are not the same thing, Having said that, my responses to the arctic are filtered through my personal knowledge and experience, and I am a political being, and so those values are integral to the work.

Leslie: Can you give examples from your work please of the themes and complex interactions that drive your art?

Jane: During my 2013 trip to Greenland I was particularly struck by the paradox of strength and fragility in the environment; seeing how there is a recovery or adaptation that takes place when conditions change. For example, the way that areas of plant growth shift according to changing conditions, how subtle variations in the ice margins reveal new relationships, how the geological story is never-ending, and how all of the natural interactions that occur represent a constant flux.

In work like Totality, for example, I am juxtaposing and overlaying imagery of lichens on rocks with eroded earth and sections of ice. The source material may be at completely different scales, but that doesn’t matter because it isn’t meant to be descriptive. One layer within the work is a map of the area I’m thinking about, drawn onto fine Japanese paper and then incorporated. In making the work I will have rubbed, scrubbed and scratched the surface, wearing it away and then building it up again, reflecting the natural processes of weathering, erosion, deposition, wetting and drying.

The same sort of complex interactions are explored in Elemental Journey, this time using imagery of ice at various scales, rocks, plants, and again a map layer. I hope that one is led to visually and intellectually explore, and also take pleasure. I hope that there is a level of imaginative transformation that entices and satisfies.

In the larger paintings that explore the notion of the ‘lost horizon’, where the states shift imperceptibly perhaps Mallaig Bheag: Breaking Through is a useful example. In this painting one can see that there is a horizon as there are two distinct compositional parts, but I think you would be hard pushed to define where that shift takes place as the brushwork, colour and tonal shift is very subtle. There is a structure also in evidence in this painting with the horizontal banding just about remaining visible.

Lost Horizon: Rannoch, is another example. Previous words I’ve written about this painting are as follows:

The sleeper train makes its early morning way across Rannoch Moor on its way to Fort William. April rain slides across the train window. Soft tendrils of cloud caress the low horizon blurring the boundary between the elements, permitting occasional glimpses of hidden hillsides. The expanse of rough moorland is pitted and uneven with peat hags and rocks. The pre-growth-season grasses largely hold on to their dun colouring, interspersed with ochre and green.

The painting is a distillation of these observations, tempered by the mood of the moment, the movement of the train, and the tentative dialogue of paint on canvas.

Here the compositional horizon is differentiated not only by the use of different colours, but by different textures too. Again the horizontal banding can be seen.

The gesture of the application of paint plays its part, and where the drag of the brush catches on scattered texture it collects and, conversely, leaves a space on the opposite side where you can see through to the previous layer.

That these ‘happenings’ can only be seen when you have your nose up to the canvas is part of my wanting to draw you in – to see the bigger picture and then to take the time to consider how it happens to be like that.

For me, this reflects how we engage with landscape itself – first take it in by scanning, and then slowly start to look at the detail, and then finally start to engage with it at a deeper level.

This detail of the compositional horizon gives a suggestion of how this line is treated, and how it is quite tentative and indistinct.

Leslie: Could you describe the art you exhibited recently at the Resipole Studios? What’s the story behind this art – its beginning, growth and development? What part did location play in that exhibition?

Jane: The exhibition at Resipole Studios was intended to be a bringing together of two bodies of work made over a five year period. Despite their being inspired by different geographical locations (Greenland, Svalbard, and North West Scotland), and their very different processes and methodologies, I was keen to explore how core values and resonances remain present, and are strengthened in the juxtaposition.

The philosophical values that I’m referring to include paying attention to the subtleties and nuances of the natural environment and the processes at play in its formation, considering the interconnectedness of things in both a spiritual (small ‘s’) and physical way, and acknowledging the richness and complexity of our human relationship with landscape and environment.

In terms of art values, my work is underpinned by a belief in visual quality and the aesthetic. I am an advocate of ‘slow art’ and want the viewer to invest time in looking, as I do in making. Despite it not being overt, I would say that my work is also underpinned by environmental values, in that I want it to have an impact on the viewer’s relationship with our climate-challenged environment, and value what is there.

Resipole Studios and Gallery is a fantastic place to show this exhibition for various reasons. The award winning gallery is owned and run by artist Andrew Sinclair and has a series of rooms each offering a different viewing experience. Despite its relative remoteness and separation from an urban cultural scene, Resipole is well connected and has an extensive audience base. For me, the location of the gallery, on the shores of Loch Sunart on the West Coast of Scotland, means that there is a strong connection between the work on display and the outside environment. The mood is set, so to speak.

Leslie: What are your compositional methods, and how do they relate to your way of seeing/experiencing life?

Jane: In the paintings, the horizon line is compositionally and metaphorically important. It provides a locus of change. I am interested in how, when one focuses in on that point there is no clear division of states but a continuum of states. There seems no fixed point at which one thing becomes another; sea becomes sky, beach becomes sea, mountain becomes cloud. It is as if by journeying ever-closer one sees that everything is of the same stuff, and part of one bigger whole.

I think that this reflects my relationship with the world – I never see things as clear-cut, but nuanced and contingent. I’m not comfortable around certainty, or people who are overly confident in their views – I can never be sure that I have all the knowledge or information needed to make claims of certainty. I like to be tentative.

This openness to contingency carries over into the way that I make paintings. I never have a picture in my mind of how a new painting will look, but have a starting point of something observed and felt, and a set of procedures that will provoke a material dialogue to occur.

I apply thin washes of colour over the canvas, usually in horizontal bands. This can be quite ritualistic and meditative. I associate the application of the paint with my own physicality and my breathing. Each subsequent application of paint is made in response to the previous layer.

A painting has a better chance of being good if I lose my self-consciousness in the process and submit to intuition. This isn’t to say that it is all down to chance, but that in blurring the boundary between the work and myself I feel there is a greater sense of authenticity in what I do.

In the smaller mixed media works, many of the same things apply. I might be making work in relation to a particular place and experience, but still don’t have a visual plan in place. In these pieces I often use image transfers of small sections from my photographs of the place, and these are randomly torn up and intuitively built into a composition overlaying a ground of watercolour washes. Subsequent layers are built and scoured back, echoing the processes at play in the formation of landscape. At some point there may be the inclusion of a hand-drawn map on a sheet of Japanese paper, which serves to confirm a specific location in my mind, along with the transfers of sections of my photographs. Other applications might include more watercolour, wax, pigment or graphite.

As with the larger paintings I am exploring the complexity not only of the landscape itself, but my relationship with it. I am not trying to ‘fix’ it, in place but to acknowledge its contingency. Each piece is a personal voyage of discovery.

Leslie: You want to combine scientific rigour with intuitive art. Can you describe how that combination unfolds itself in the art projects you’ve worked on?

Jane: I’m not sure that it is necessarily scientific rigour that I want to incorporate in my art, but scientific knowledge and influence, and I think that it is present in various ways in different projects.

First though, I’ll give a bit of background. For the past thirty years I have been in the company of scientists as much as artists. In one incarnation I worked as a cartographer in an Environmental Science department in a university, and my understanding and knowledge of environment became influenced by the conversations and culture around me. Added to that, my partner is a geologist and our shared field trips and conversations resulted in my viewing, thinking about, and engaging with my surroundings in an expanded and scientific way.

I have actively undertaken projects alongside scientists, and presented my work in scientific contexts. For example I travelled to Arctic Svalbard in the company of atmospheric scientists and engaged in a shared field period, resulting in an exhibition and publication called Arctic Dialogues. I have presented papers at conferences and meetings about the role of art in conversations around climate change including at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centres in Italy and in Brussels.

The work relating to the field period in Svalbard saw me taking directly from the scientist’s working practices and procedures, and using them to make artwork. We were there spanning the time of the polar sunrise with the aim of collecting snow samples to see how the arrival of the sun affected the behavior of POPs (persistent organic pollutants) in the snowpack. The snow samples were melted and then filtered, with the filtrate returning to the lab in the UK for analysis. I was intrigued by the 5 cm diameter filter papers, with their residue of carbon from local coalmines, which were being discarded by the scientists. These tiny discs became the focus of my attention and the starting point for a whole new body of work.

I do like the word ‘rigour’, with its connotations of attention to detail, diligence and focus, and these are values that I hope are present in my work and working methods. For example, in making the larger paintings I tend to have a standard set of procedures/actions which I more or less stick to, and which provide a framework out of which unexpected results can occur.

In that sense, it’s not far removed from the way a scientist might repeatedly conduct an experiment looking for difference in results. The notion of repetition is key for me as it provides a stable basis from which magic can occur. On reflection I could say that for each new project I develop a set of rules that provide the framework for the development of the work.

Leslie: What do you see as your artistic role in relation to your birth culture and contemporary society?

Jane: I don’t actually think I’ve got a role – I think that I’ve got an itch that I have to scratch, and that’s probably the extent of it.

I have mostly chosen to not think about it out of fear that it might get in the way of me getting on with making art. I think that currently anyone and everyone can decide to be an artist if they wish, although I do question what that might mean for art.

I would like to hope that what I do has meaning and resonance even for a small number of people. If one of my paintings touches someone on a level beyond words, or it opens an emotional door for them, then I am fulfilling my aspirations.

Next week’s interview will feature the founder of Climate Museum UK, Bridget McKenzie.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

One Response

Thank you for that inspiring dialogue.