Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

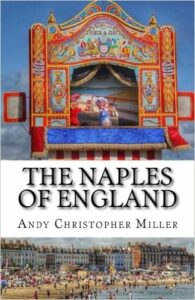

I interviewed writer and psychologist Andy Miller, winner of the 2011 Yeovil Poetry Prize, about mixing genres as an author. In the first part of Andy’s interview he describes how his fact/fiction book ‘The Naples of England‘ grew out of his childhood in Weymouth and some tragic family secrets.

Leslie: In writing your book ‘The Naples of England’, what decided your choice of memories – and to what extent were you adapting rather than literally recording your own upbringing?

Andy: ‘The Naples of England‘ had an unusual journey to publication in that it was originally intended to be part of a hybrid of memoir and literary fiction combined in roughly equal proportions. Some years ago now, I set out to explore, and did in fact complete, a full book-length piece about family secrets and, specifically, the suicides of my two grandmothers.

I had felt encouraged in this experimental approach after reading an article by Chimamanda Adichie in 2013. In this she had called for “… a new form, a cross between fiction and memoir…” arguing that while memoirs appeared to provide “… a prepaid label of truth… they can often also be subject to a self-censorship that protects the ‘I’ character and the writer’s loved ones.” Fiction, on the other hand, she said “… by its very nature, creates the possibility of a certain kind of radical honesty that memoir does not.”

In addition to telling of my own attempts to navigate around and discover more about the secrets and extreme sensitivities in my family that I had stumbled upon almost by accident in my thirties, I was also attracted by the challenge presented by Adiche.

I sometimes viewed my finished piece as a sort of filled omelette. My direct, first-person memoir was the filling over which a parallel fictional story was folded. I also enjoyed the attempt to have my fictional characters themselves wrestle with the dilemmas arising from the fiction/memoir contrasts and challenges.

Alas, my literary reach exceeded my grasp. I did manage to get an initial submission in front of the late Carole Blake, from Blake-Friedman Literary Agents, and to my amazement she asked to see the full manuscript. Carole was very generous with her time and, whilst not accepting the book, gave me detailed and encouraging feedback on what I had written. The one piece of advice that immediately jumped out from her report was, however, “Lose the memoir!”

I was loath to just junk this middle section. In fact, during the actual writing I had developed a real affection for it. But I also knew that I would be a fool to ignore the advice of one of the best agents in the business. So, as well as excising it from the novel, I forced myself to consider my own motivation for including it in the first place.

Was it just an indulgence, a ‘love letter’ to a particular time and place – a council estate in a south coast seaside resort in the eighteen or so years immediately following the second world war? Was I opting for easier and more familiar material because I was, in fact, unable to meet the creative demands of a full-length piece of fiction? Why had the fiction-memoir hybrid seemed such an enticing choice in the first place and what was I really trying to achieve?

After a long and sometimes dispiriting period of wrestling with these concerns, I began to articulate for myself a clearer rationale. My late discovery of the tragedies in both my parents’ lives had presented me with several questions that I found very hard to answer. Foremost among them was my disbelief that, as a reasonably intelligent and curious kid, I had never asked about the identities or lives of my two grandmothers. Both my parents talked frequently about their earlier years, before and during the war, but had somehow managed to weave all their accounts so that they omitted reference to these two women. I was genuinely shocked at what they – and I – had accomplished. And as a practising psychologist by then, I could not help but reflect on a lot of questions about family dynamics, repression and denial!

Twenty years after my family and I had left the town, and in my early forties, I happened to revisit the house in which I had spent my first eighteen years. On impulse, I knocked on the back door and it was answered by the current occupant, a dishevelled lorry driver who had been sleeping off a Saturday lunchtime drinking session. I blurted out that I had grown up in the house and he immediately said “Oh yes, you must be … there was that suicide wasn’t there? Your Mum or someone?”

This was the biggest shock of all and the one that propelled me into completing ‘The Naples of England’ and to a great extent fashioning its form and content. Whereas I had assumed that my dead grandmothers had somehow vanished quite quickly from everybody’s memories and, hence, their lack of mention, this incident forced me to realise that their suicides were still very much remembered long, long afterwards. That I had, somehow, been shielded during my growing up, every day really, not just by my parents but, unbelievably, by a whole community!

Now that I had a clearer understanding of what was driving me to write, the task became much easier and hugely more enjoyable. Having toyed with the idea of a set of short stories originating from incidents in my growing up, I settled finally on producing a set of vignettes spread across this period. The incidents I explored included my mother’s suppressed horror at the atrocities of the Nazis during the war, my small number of favourite teachers, the freedom to roam far from adult supervision, the terror of dodgy men encountered during these wanderings, the wonders of the natural world and our local library, the casual cruelty of some children, especially towards animals and birds, and sexual awakening accompanied on a grand, national scale by the Profumo affair. And I did have a wonderful landscape in which to set it all.

Much or all of this is standard fare for memoirs of that period. But underneath the stories I was recounting, and operating then mainly at an unconscious level, was the theme of being protected, by the state and local neighbourhood as much as by my parents. And this kindly supervision produced its own dilemmas, feelings of being stifled, constricted and not knowing the whole truth competing with a sense of being cared for and protected.

Once I had embarked on the writing, the incidents that I ended up including seemed pretty much to select themselves. I suppose I structured the contents so that the pieces covered the time period in a fairly even fashion, and I did change names and locations to give myself more freedom in the writing. And, yes, I did invent a few incidents to give one or two pieces a more satisfying narrative arc. But I think the emotional heart stays faithful to my experiences and reactions and I am very happy with the resulting book.

I have been pleased by the book’s critical reception since publication. Some experienced and successful writers have responded extremely favourably, and I am gratified by their comments and reviews. While I am happy to have written something that chimes with the lives and experiences of others of my generation and with people who also grew up in South Dorset, I perhaps value most the comment from an ex-colleague who was a generation younger, female and grew up in a back-to-back in Liverpool. She wrote that the book reminded her so much of her own upbringing!

And writing, self-publishing and promoting ‘The Naples of England’ through various talks did also, at last, enable me to concentrate on the novel I had originally embarked upon.

‘Never: A Word’ is now complete and beginning its search for a publisher.

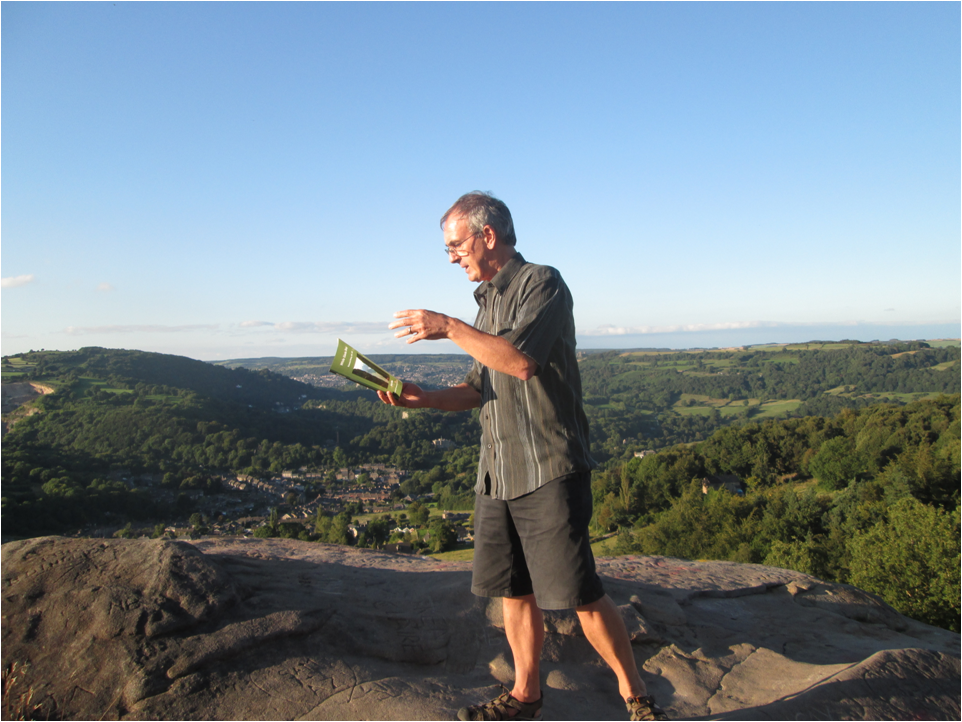

Next week, in part two, the featured image of Andy Miller reading on a mountaintop is explained! Andy also tells the story of his next two books, both involving mixed genres.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Thank you for making such a lovely job of this, Leslie

🙂 🙂 🙂