JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

A piece about how the writer’s imagination works, using examples from my recently published novel, Love’s Register.

A piece about how the writer’s imagination works, using examples from my recently published novel, Love’s Register.

My thoughts about writing Love’s Register begin with the image of the novel as a house of cards. What I see is an interlocking structure where each word has to be added carefully, judging how much weight it can bear. If the words hold together they support each other, if they don’t the whole caboodle comes tumbling down.

But to keep up that balancing act all the way is difficult. It’s a long journey and a well-judged finish – whether it’s a denouement or a reveal – can make all the difference. It’s what I look for when I read with a novelist’s eye, comparing the quality of the first and last chapters.

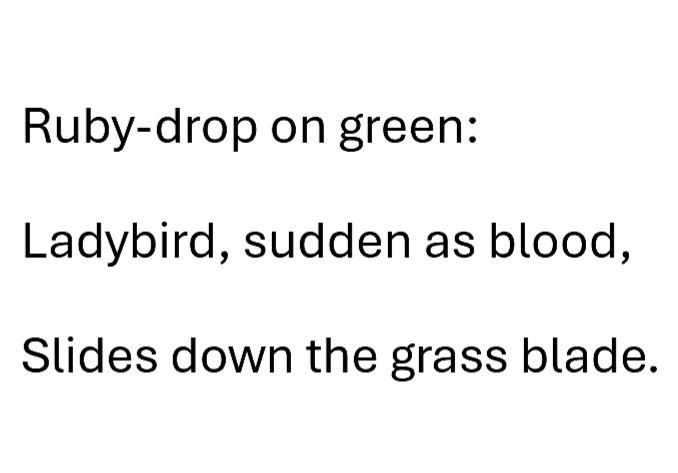

Taking that as my starting point, the beginning of Love’s Register reads:

While the end of the book , about climate change, reads:

So the book moves from introversion to extraversion, from soul loss and alienation to images of world emergency and nekyia. But, of course, the characters move with it as they grow, pushing the story towards a character-driven ending.

Thinking more about the images that might fit a novel, I came up with three more:

But the image that keeps coming back is the novel as a symphony. Why? Partly it’s the effort involved, but also its length, subdivisions and historical conventions. Because although the novel appears to offer almost total freedom, those conventions still act as signposts and boundaries.

To give a few examples from Love’s Register:

To sum up, a novel benefits from a) a sense of flow/connection between passages b) a mixture of formal and informal registers c) speech that is part of the narrative drive.

One final example. I worked on this transitional passage between Beth’s love affair and the climate story using:

Leslie Tate

ABOUT THE BOOK:

Love’s Register tells the story of romantic love and climate change over four UK generations. Beginning with ‘climate children’ Joe, Mia and Cass and ending with Hereiti’s night sea journey across Oceania, the book’s voices take us through family conflicts in the 1920s, the pressures of the ‘free-love 60s’, open relationships in the feminist 80s/90s and a contemporary late-life love affair. Love’s Register is a family saga and a modern psychological novel that explores the way we live now.

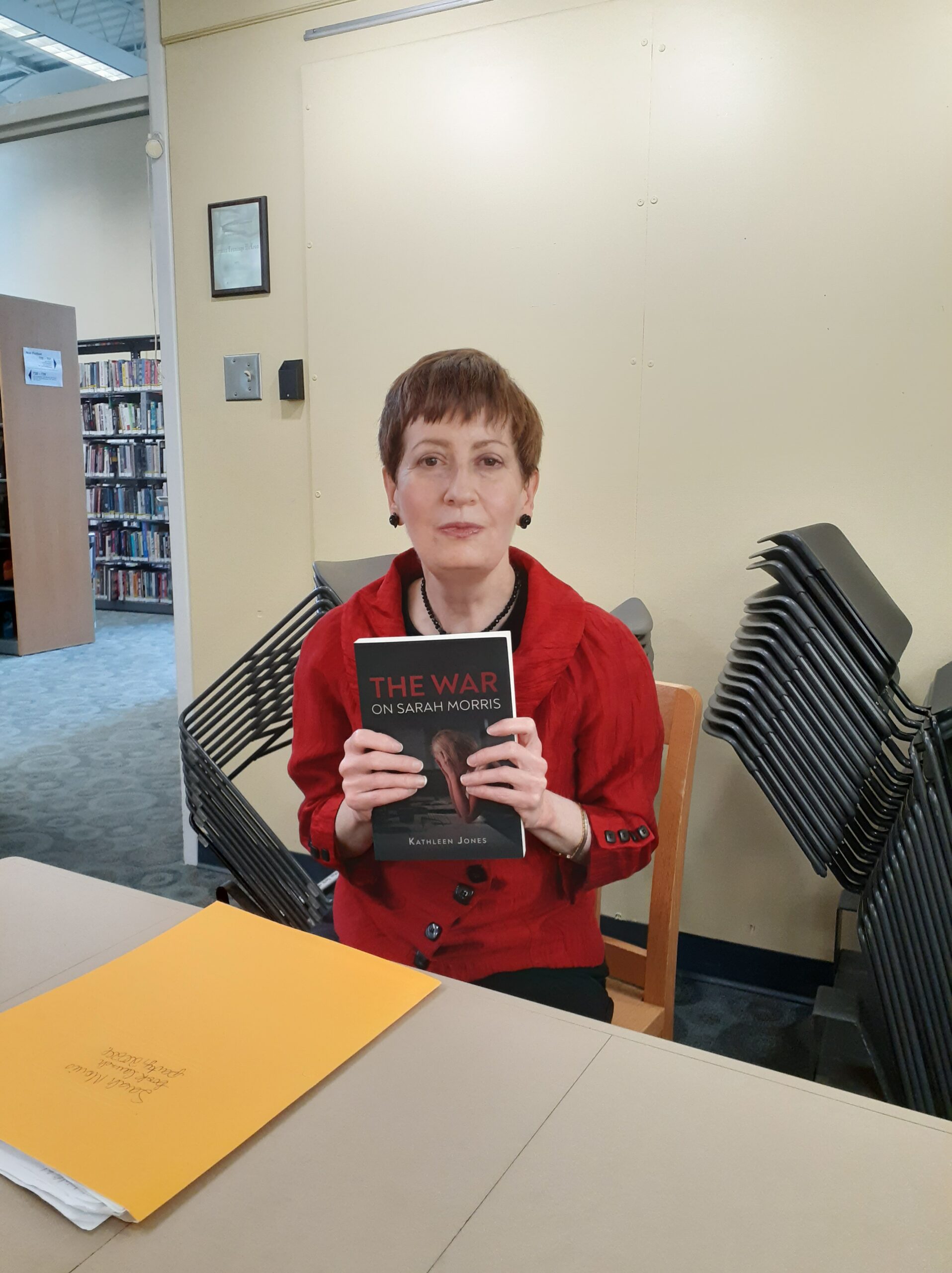

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

This article is very interesting, Leslie. I like your continuation in the thought process from the beginning to the end. A lovely extract. Sharing.

Thank you, Robbie. Praise from another author is very special. ?☀❤

This is very beautiful, sad and brave and full of love and loss, like everything that matters in the arts. I ask myself whether I would feel your words so deeply if I didn’t love you so much, and I believe I would. I’d want to read this book and I’d be glad I did. xxxxxxxxx

You inspired me, Sue, and helped as my Beta reader – and to bring out my best self. 🙂 🙂 🙂