JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

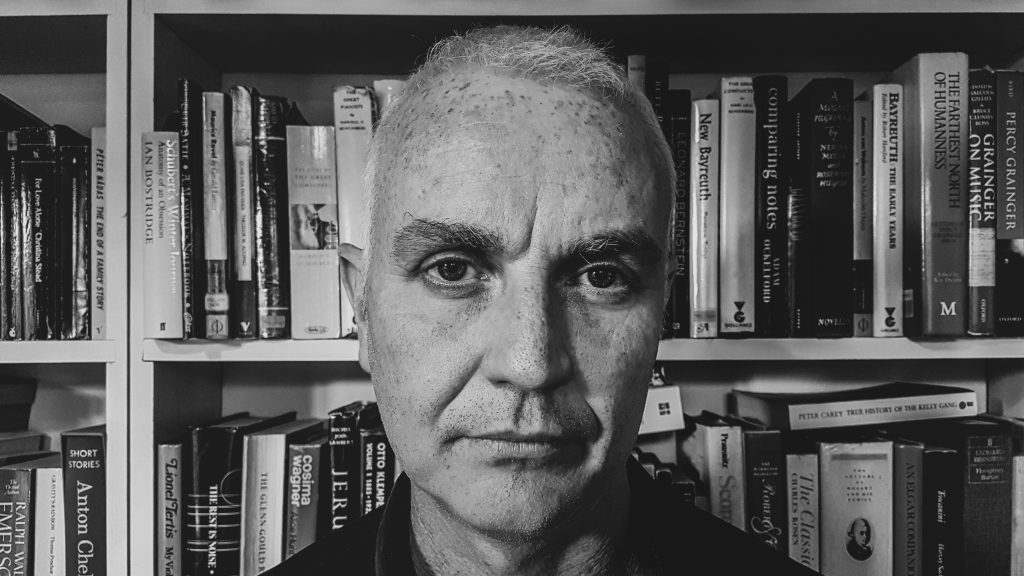

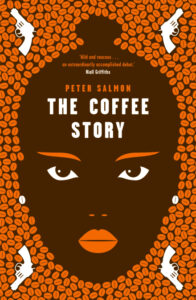

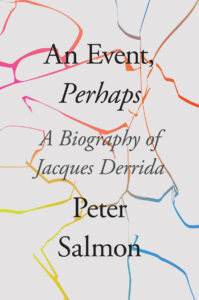

I interviewed Peter Salmon, whose first novel, The Coffee Story, was a New Statesman Book of the Year. Peter talked to me about his recent biography of Jacques Derrida, An Event Perhaps, and the nature of writing that pushes the boundaries. Peter Salmon is the former Centre Director of the John Osborne/The Hurst Arvon Centre.

Leslie: What have been the key experiences from childhood, boyhood, youth that led to your adult writing? How has writing as an adult changed you?

Peter: It was books that led me to writing. I grew up in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, and I think we can say literary culture is not strong there. So I loved to escape into the unimaginable places books would take me. Family legend has it that I would ignore all the illustrations in picture books and ask again and again what the words were. I still love words above pretty much everything else.

Two very different books had a major effect – the first, hilariously, is Centennial by James A Michener. I borrowed it from the school library at the age of 11 specifically because it was the first book I had ever seen that was over 1000 pages long. I hadn’t read melodrama before, so every cliched plot twist had me genuinely gasping. Thanks to James A for giving me a love of ‘ta da’ moments I’ve never quite shaken off.

The second was Crime and Punishment at about 16. I went from a cheerful maths whiz to a morose dressing-gown-wearing existentialist in about a week. Still can’t go back to it. Freaks me out.

Writing as an adult – I think the main thing is getting to know the ‘craft’. Writing properly is not just getting thoughts down, it is genuinely loving the way that literature is ALWAYS wiser, funnier, more interesting than the author, if you let it work is magic. It’s a privilege to work with it, and get away from the dull stuff that normally goes on in my head.

Leslie: Tell us about your novel The Coffee Story – in what ways is it necessarily difficult and complex? How did you go about building a complex, expressive work in words?

Leslie: Tell us about your novel The Coffee Story – in what ways is it necessarily difficult and complex? How did you go about building a complex, expressive work in words?

Peter: I think for the most part I went about it badly – but I think that’s actually the way one writes books. The hopefully reasonably coherent thing that ends up on the bookshelf is a collection of purple patches, lulls, weeks of indecision, plots that went nowhere, characters excised, too much research, too little research, and bits you really liked that everyone told you were rubbish and so you cut them out. The trick of course is to hide that fact as successfully as you can.

With The Coffee Story, the first 20,000 words came to me without pausing for breath – and then it all got very hard. You created these characters and off they go doing stuff – trying to land the plane without it all seeming contrived is a killer of a problem, and one you can’t learn to do any other way than doing.

Which is, of course, the glory and horror of making books – the solution to most problems is to keep writing. Let the medium solve it for you, if there is a solution. I am a huge believer that all ideas you have sitting around are stupid. This is why ‘waiting for a good idea’ before writing your masterpiece is wrong. As I said above, books make their own wisdom, and produce their own ideas. You have to write your way though the problem. And the cracker is that there is absolutely no guarantee you end up with something that’s any good. If a book dies after 80,000 words, then it dies. That’s the game you have to decide to play of you want to write.

Leslie: In writing An Event Perhaps, a biography of Jacques Derrida, you had to make difficult writing accessible. What were the strategies as an author you used to accurately capture Derrida’s thinking without over-simplifying it while making it easier to understand?

Peter: A lot, lot, lot of reading. I was very aware that for most people – myself included – Derrida is incredibly difficult to read. There are no easy ways into his work – even someone like Heidegger starts his whole philosophical project with the statement ‘The meaning of the question of Being has been forgotten’ – ok, that’s what he is going to investigate. Derrida arrives, as it were, fully formed. I had to absorb a lot of stuff before it all started to make sense.

Peter: A lot, lot, lot of reading. I was very aware that for most people – myself included – Derrida is incredibly difficult to read. There are no easy ways into his work – even someone like Heidegger starts his whole philosophical project with the statement ‘The meaning of the question of Being has been forgotten’ – ok, that’s what he is going to investigate. Derrida arrives, as it were, fully formed. I had to absorb a lot of stuff before it all started to make sense.

But then the trick is to be able to step back from that and say, ok, so what is the question he is trying to answer, or at least raise? He is, after all, just a bloke thinking out loud. Take something like ‘the metaphysics of presence’ a forbidding concept. Well, this bloke reckons that what stabilises a system is something outside the system. Example – all of Western religion is based belief in God, but God does not appear. Or all of law is based on a belief in Justice – but true Justice is impossible. Philosophy is based the search for Truth. But Truth is unattainable. So what this bloke thinks is all of these fields are generated by these terms. And what is interesting is that they are being generated. Not that they will get to their goal.

And in literature – you cannot have a coherent text. There will always be contradictions, things left out and so on. You are at a nice party, having a nice time, everyone is nice. And then someone points out that everyone there is white, middle class, and so on. Until it is pointed out the whole thing seems to be apolitical. But surrounding any party, any books are exclusions, decisions, cultures. Derrida forces us to look at what is left out, and what this means. It straightforward in the end, but the implications are what he spends his life teasing out.

Leslie: When people are taught to write fiction they’re often told to: show not tell, go in fear of abstraction, cut out adverbs & adjectives and avoid flashback. What are your ‘unwritten rules’ for imaginative writing?

Peter: Got to stay I’m a bit of a stickler for this sort of stuff – I do a lot of copy-editing and manuscript assessment, and I won’t say every book that fails to follow this stuff is bad, but I will say that every bad book is because of it. Adverbs are the enemy of all that is good – they are, after all, a way of telling not showing – if you have to say a character looked up confusedly then you haven’t done the work to make the reader know how they would look up. In fact, when I finish a piece of writing I do two things – a search for ‘–ly’ and a search for the word ‘had’. Both are killers. Simple test, if sentence has either, take it out, and 99% of the time the sentence will be better. Prove me wrong!

The only rule about imaginative writing I hate is ‘write about what you know’. Ok, it might be a way to get past a block, but if it was true I’d basically be writing about being a middle-aged, middle class, white heterosexual man who spends his days editing and occasionally popping to the shops. We have been given literature to explore glorious lives being our own. I much prefer what Rebecca West said – ‘I write to find out about things.’

Leslie: Would you like to define/give examples of + comment on any current form(s) of writing that particularly interest you?

Peter: I absolutely love writing which pushes the form to its limits. I hate ‘realism’ to be honest – a realist novel is simply one that is pretending it is an unmediated telling of a story. Every story is a construction, so I much prefer when a writer is open about that. Someone like Gerald Murnane who wrote something like ‘If I say in a book that a man is walking down a street, the last thing I want you to do is imagine a man walking down the street.’ I think that when it comes to painting, for instance, people are very open to there being a million ways to paint a bull, and the criteria they use is not simply ‘whatever looks most like a bull.’ A Picasso bull is a marvellous and strange thing, and I like writing that does that.

Murnane is, I think, the one great genius writing at the moment – difficult, often irritating, but books like The Plains and Landscape with Landscape are extraordinary. I’s also throw in Mathias Enard – his book Zone is one of those where you start to read it and realise how good a book can be if you are prepared to risk everything.

Leslie: Why do you write?

Peter: I write because books are the best things in the world! I am, unfortunately, not one of those people who is driven to write – I don’t have a whole load of journals, or juvenilia. I can happily forget to write for years at a time. But when I do it – it’s just insanely pleasurable when it is going well, and insanely fascinating when it’s not. And at the end, you have a book, that someone might read and enjoy. It’s a glorious thing!

Leslie: Tell us about your forthcoming book and how we can order it.

Peter: So, An Event Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida came out on October 13 and is, I hope, at all good bookshops. Lovely if you can order it via your local bookshop – they need our support, but its also available directly from Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/books/3678-an-event-perhaps

Thanks for asking me to do this – great fun!

You can listen to Peter Salmon discussing his book An Event Perhaps on BBC Radio 3’s programme ‘Free Thinking’ here.

Next week I interview international poet and translator Mark Statman

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |