JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

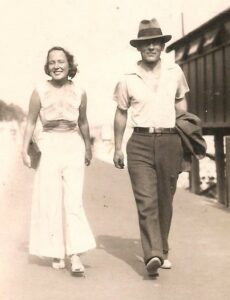

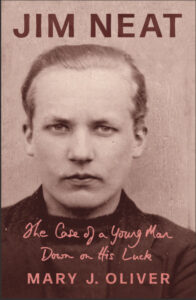

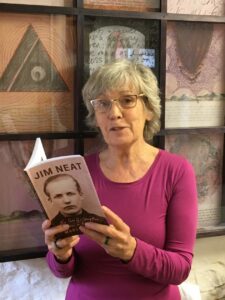

I interviewed Mary J. Oliver about her debut novel Jim Neat , which uses an original mix of prose, poetry, found documents and photographs to uncover the secret history of her father as a vagrant in Canada. Jim Neat ranges across 20th century history, adopting a legal structure to ‘make the case’ for the worth of Jim’s life.

Our archives are a dream-like portal to our unwritten histories – Mary J. Oliver.

Leslie: Your debut novel Jim Neat is a collection of documents putting a legal case about your father. Can you explain why you adopted this structure and what you set out to prove, please?

Mary: My plan was always to explore Jim’s life from the perspectives of those who knew him. It was only in the very last stages of creating the book’s structure it occurred to me that what I’d done was present a case for him and that the voices were his witnesses.

I think I proved that ordinary, uncelebrated, dismissed, marginalised people, under close scrutiny, are a lot more interesting than royalty, prime ministers and army generals.

Leslie: What set you off with this project? How did you begin and then bring together the various parts of the book?

Mary: My father existed on the edge of the family. He was so absent in spirit and his past so hushed up, he was a complete mystery to me. This felt normal, I never questioned it. But twenty-five years after his death, a dark event occurred in our family which high-lighted feelings of alienation that I’d also experienced. Realizing that we’d both been excluded from the heart of the family, it seemed odd that he and I’d never bonded. I felt an urgent need to find out why, and who he was.

Leslie: What were the ups and downs of the research process? How did you craft and condense the material you’d got into ‘a small work of art’?

Mary: I loved every minute of it.

Early research into unknown family members was productive; they were hoarders and had vast quantities of invaluable letters and documents. Tracking down unheard-of cousins and going into their attics was brilliant fun.

I read voraciously and had to get a new bookcase. Wider research coincided with the digitalisation of archival material. In 2008, I contacted Fremantle Library, in Western Australia, about a newspaper article that I knew had been written in 1923. A librarian tried but failed to find it. In 2016, eight years later, out of the blue, she emailed me to say that all Fremantle newspapers had been digitalised, she’d traced the article, and there it was, an account of my father, accused of burning the carcase of a horse and fined £6 for swearing in public!

Then there was my journey across Canada in Jim’s footsteps. This helped me understand the scale of the place from the viewpoint of someone seeking non-existent work in the 1930s. It felt magical, actually, standing where he’d stood among ancient trees in the forests of British Columbia. From the front of a Greyhound bus, I watched the prairies fly by, hour after hour after hour, imagining him hitch-hiking the distances. I knocked on the door of the renamed Bethany Home for Unmarried Girls and Illegitimate Babies, where he’d been thrown down the steps (the nurses were super-friendly to me). The grandson of Jim’s friend, Adam, drove me to the black community’s Shiloh Cemetery, beautifully maintained by him to this day. I saw the ruins of Whitby Hospital and Toronto Jail. I couldn’t have written as I did without having experienced this journey.

Leslie: Why did you feel something ‘concise and spare’ was the best aesthetic approach to your subject?

Mary: After five years of research, what had started out as a mini-crusade was turning into an unwieldy, mish-mash. Nobody was going to be as fascinated as I was with the minutiae that I’d amassed.

With a background in fine art, I was familiar with the process of making a work of art ‘work’, but I had no specific training in the skills of writing. So I set out to learn. One of the most important lessons was distillation – and I approached this in two ways; one was to recast a lot of the prose as poetry; the other was to delete huge chunks altogether. For instance, I created my own detailed back-story for Lizbietta (Jim’s lover in Saskatchewan); I imagined her mother’s emigration to Vancouver; her grandmother’s life in Ukraine; their tragedies. That all got the chop and I just hoped that my ‘knowing’ her background, gave her character authenticity.

A concern I had prior to publication was that I’d condensed the story by a factor of about 90%, and had no idea whether the remaining 10% made any sense to a new reader. I’d lost my objectivity. It wasn’t until my first public reading, at the North Cornwall Book Festival, that I relaxed. We were in a beautiful tent being battered by a violent storm and I could barely make myself heard, but the audience fell in love with Jim straightaway, I could tell. I was home and dry.

Leslie: Emotionally, what were the barriers you had to overcome before you could write about your father?

Mary: I don’t think I felt there were barriers. I was driven (because of the dark event that I mentioned), compelled to unravel the mystery of my father.

I wanted the book to be about Jim, not me. The short MS that I submitted to Seren Books, was his story up to the point he was deported from Canada, back to UK, and it ended with my birth. Seren accepted it for publication but asked if there was more. I said there was, but I wasn’t willing to share it. Well, they twisted my arm.

Leslie: How did you make sure that the book was a work of literature and not just a therapeutic piece?

Mary: The therapeutic process played a role, definitely. But it was only a stage. After the explosion comes the tidying up. I’m familiar with this in my visual practice; I might scribble using a floppy brush held in my left hand, eyes closed; put it aside; return at a later date; see what there is to develop; this might mean working on it upside down, but mindfully this time. Similar to warm-up writing exercises when you write random thoughts without stopping for ten minutes; go back later; highlight and develop the startling bits; delete the rest. I find it easy to be ruthless about recognising what needs to go. I love the whole process, allowing that initial, emotional outburst, right through to honing it to perfection. Or as near as you know how.

Leslie: Can you give examples of how you have adapted fact to fiction and changed the story using your imagination? Why did you make those changes?

Mary: I had so few facts to go on when I started. He’d rarely spoken to me. His life was nearly all gaps. After years of research, based on fragments, there were still many gaps. Some of these gaps, I wanted to fill, even if it meant making it up. But everything I’ve written feels emotionally true. What I fictionalised grew out of genuine fragments. There are still gaps of course; people are left wanting more, but that’s a good thing, I think. What remains unsaid in the book is imagined by the reader.

Mary: I had so few facts to go on when I started. He’d rarely spoken to me. His life was nearly all gaps. After years of research, based on fragments, there were still many gaps. Some of these gaps, I wanted to fill, even if it meant making it up. But everything I’ve written feels emotionally true. What I fictionalised grew out of genuine fragments. There are still gaps of course; people are left wanting more, but that’s a good thing, I think. What remains unsaid in the book is imagined by the reader.

The only totally fabricated character is Sergei, Lizbietta’s step-brother who, on discovering Lizbietta’s body, becomes mute for the rest of his life. I used that conceit in order to provide a graphic account of her death.

The Hospital Case Notes are imagined, based on letters that Dr Fletcher sent to Queenie, Jim’s sister. Lizbietta’s Diary is imagined, based on family legend and hearsay.

Leslie: What were the moral issues you faced in writing about actual people? As a writer and a person with a conscience, how did you try to deal with the possibility that you might be misrepresenting someone?

Mary: To start with, it didn’t occur to me that I was writing a book that might be published.

Jim had been dead a long time, was thoroughly forgotten. His name was never mentioned, or if it was, it was to demean him. I just wanted to find him.

Once I knew it was going to be published, yes, I was anxious that some family members might cause trouble. I didn’t want trouble. So I deleted anything libellous – an interesting challenge, because there was the obvious danger of losing dramatic impact. But I think it was a case of less being more.

Also, the therapeutic process had done its job by then; I was ready to let go of stuff. I no longer resented anyone. I’d grown to understand why it was as it was.

Leslie: How did your life as a teacher and collaborative artist prepare you for Jim Neat?

Mary: My visual practice was predominantly collaborative, usually involving people who weren’t trained as artists, but getting their work exhibited in galleries. That was my prime interest and passion, my belief that everyone is amazing and everyone is creative, given the opportunity. And yes, this conviction is at the core of Jim Neat.

Since the book’s publication, I’ve been asked to run workshops based on the importance of writing our own histories. I’m tired of traditional history and find ordinary and marginalised figures and communities far more interesting. Get those items down from the attic, I say! Draw, scribble, collate, research, expand, distil, structure, restructure. Fill in the spaces of history. Our archives are a dream-like portal to our unwritten histories.

Leslie: What is the process that has gone into being published at a late stage in your life?

Mary: I started writing Jim Neat after I’d taken early retirement due to health reasons – reinventing myself as a writer cured me. The book’s still keeping me busy, especially since it was picked up by a producing-writing team, who are developing an adaptation. It’s early days, but they will be looking for potential production partners in the UK and Canada.

I feel incredibly happy to have given Jim back his life in this way. The sadnesses are all there still, but I accept them more easily now.

Next week I interview I interviewed author and aerial performer Sarah Jane Dobbs , whose novel Killing Daniel was nominated for the Not the Booker Award.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

4 responses

This is an intriguing post. I can imagine Mary’s fascination with her father’s story. I also understand the concept of fictionalising parts of the story to build it. I had to do the same thing with my mom’s story because she can’t remember the details. She remembers highlights and I have to write around them and build them in. A great post, Leslie.

Yes, the act of fictionalising a personal history around what we call facts can change how we see ourselves. That, in turn, can change how we act and who we are. It’s the power of stories!

So appealing to me. A challenging and fascinating story I’d imagine. Sounds very inviting! I love digging in to people’s lives…and what makes them tick. Thank you.

🙂 🙂 🙂