JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed Lewis Stockwell about his Natural Aesthetic Canoe Journeying, his deep involvement in nature and his CFS-M.E. condition. Lewis is an artist, a curriculum innovator and a Programme Leader for @uhoutdoors at Herts University.

Leslie: Can you trace for us, please, the development from childhood onwards of your love of nature.

Lewis: I wish I could say that I’d always felt deeply and consciously connected to nature, to the more-than-human world, as I do now. I can’t honestly say that I have. I was never the kind of child who littered or who destroyed plants; nothing like that. Nature was something in the background. The place in which all events happened. In school, it was something left alone in the ‘conservation area’.

That said, I remember as a child tending to do the birds in the garden. It would be my job, as bestowed to me by my nan, to head out (in all weathers) to the bird feeders. She had about 5 on this ageing apple tree. All different feeders for different kinds of birds and different feed, of course. She would stand at the kitchen window and watch them with joy – sometimes she would even head out and attempt to whistle them closer. That’s a legacy she’s left me and I do the same now (I even whistle in the hope they won’t be too disrupted by my presence when I go out to feed them!). I even continue to throw feed onto the ground so that the larger birds find food.

Talking of legacies, another significant influence on my love of nature and my connection to it was being an Air Cadet. Now, I know that people have mixed views about these kinds of youth organisations and that part of my life has run its course, but without it I very much doubt that I’d be able to read a map, identity flora and fauna, or have the skills to respectfully navigate the world with a kind of natural integrity that would have been otherwise absent in my life. I am no advertisement for uniformed youth organisations but there is an important aspect of a community such as that. I learned through fieldcraft and to a degree, some adventurous activities, the actual relationship humans tend to have with the natural environment and the potential for something better.

During my undergraduate degree, my then girlfriend and I began to visit the Lake District. I remember the first time of coming into the landscape and being overwhelmed. The beauty of the landscape was something that felt so special, so beautiful, that when my wife and I decided on locations for our wedding, we got married on Lake Windermere.

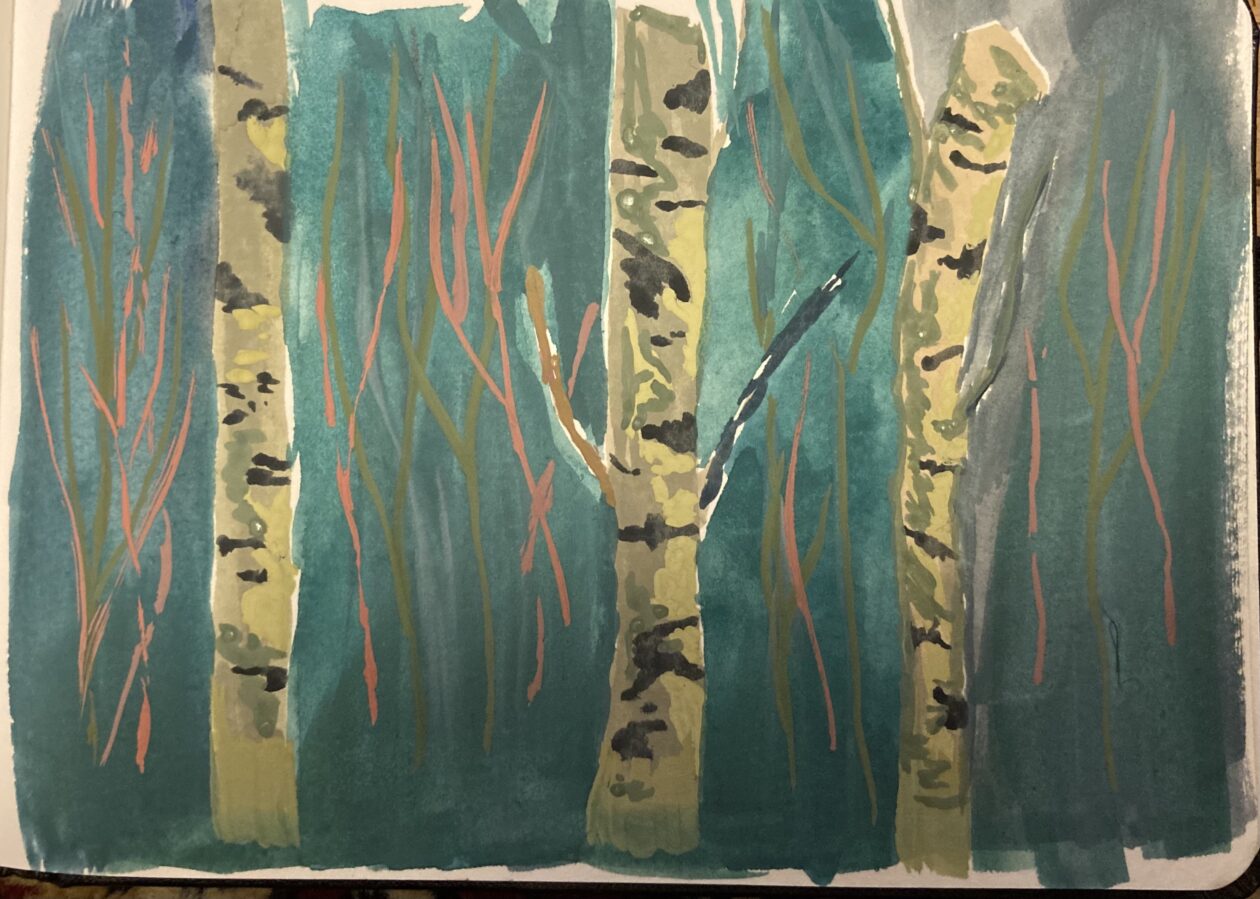

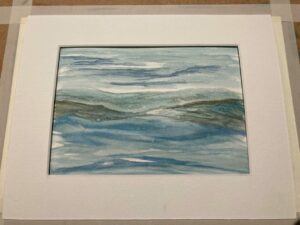

More recently in adulthood, I took up canoeing. Normally this is categorised as an ‘adventurous activity’. This is sometimes seen as a thrill-seeking, character enhancing, experience that is valued in its humanistic contribution rather than expanding one’s identity to be part of nature. Don’t get me wrong, anyone who wishes to learn a paddlesport needs to know the skills and gain confidence to be safe in the craft and on the water. There is, in my view, an often-missed opportunity to teach and learn about how humans relate to the natural world by being in unfamiliar situations, new places, or disruptive experiences. There is something about being on the water with a finely moulded, 2-3mm thick material keeping you buoyant and dry, that brings a new dimension to one’s place in the world, as part of nature.

This, I suppose gradual process, has led me to think really deeply about how humans perceive the world around them and the role of education in directing generations of students away from concerns for nature, by often teaching abstract information devoid of a sense of place or purpose.

For me, now, I am not above nature, but a part of it. I’m still working out what my role in the ecosystem is, but educating those who have lost their way and those who have yet to make a much more meaningful contribution to their environments is where I think my natural integrity sits.

Leslie: Tell us about your Natural Aesthetic Canoe Journeying. What’s the aim of the activity and how does it differ from white-water rafting, please?

Lewis: Great question. So a canoe is a really versatile craft, which originated in the Asia Pacifica region millennia ago and gradually made its way westward to the Americas, where it was adapted to local landscapes and uses by First Nations Native Americans. It is a craft that can be paddled solo or in groups (depending on the size) and has different designs for different uses; most canoes today are generally designed for accessing all types of waters, including white water, shallow waters, lakes and in some cases, seas.

Often, white-water rafting is engaged with for the thrill, fun and adventure we might associate with it. Ultimately though, whitewater rafting is done in groups, with each person playing their role in keeping the boat moving and upright; it is much more likely to happen on moving water than in sheltered quieter creeks, which is where you may often find canoeists.

Canoeing is a full-bodied experience. We use all of our senses, thinking capacities (cognitive, embodied, affective) to respond to the immediate demands and opportunities of the environment. In a canoe this could be keeping balance, literally going with the flow, or finding the sweet spot to make the paddling a breeze.

Journeys are different from any old kind of travel. We know when someone has been on a journey – they are different at the end. Full of stories, new ways of seeing and engaging with the world, often drawing on new motivation and discipline as a result. One philosopher, Ronald W. Hepburn, argues that a journey leaves one’s sense of reality lastingly disturbed. It is these kinds of aesthetic opportunities from journeying, coupled with the affordances of the canoe, which enable a range of educational opportunities for the solo paddler.

Leslie: What’s unusual is your philosophical and aesthetic perception of nature. Can you explain what this means in practical terms?

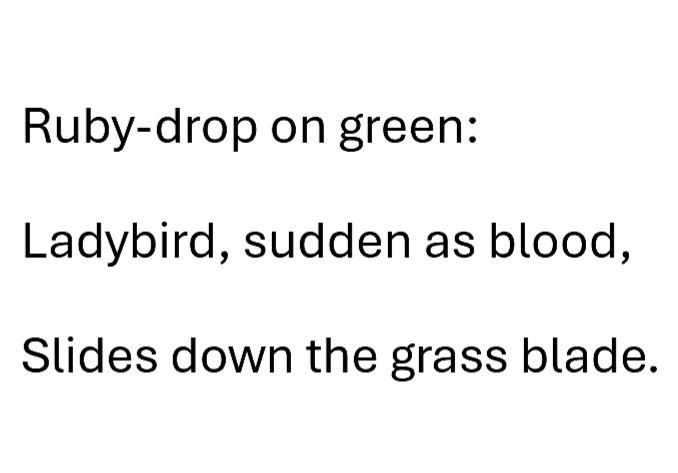

Lewis: Practically, what this means is that I’m looking for ways in which philosophical thinking can challenge common sense thought and action in, of and for nature. One really interesting area where I think we see a lot of thoughtful, challenging and insightful philosophy is in nature writing. I think this is a good place for people to see the practical value in thinking philosophically about nature and the concepts we use to discuss nature. So while I am often trying to understand the scientific conceptualisations of nature and the impact of humans on nature, coupling this with rich writing about the sense of loss, or beauty, about home, or accounts of farming, help to create a rich, and generalist (or as some prefer ‘multi-disciplinary’) way of understanding which is much more representative of the human experience than abstract philosophy or objective science can provide. I think that’s way I’m taken with aesthetics philosophy – it is underrepresented, often misunderstood, yet connects many areas of more-than-human and human existence and action.

Leslie: How do you manage your CFS-M.E. when involved in strenuous outdoor activity?

Lewis: Great question – often badly. My Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is coupled with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Severe Depression, so there is a double-edged sword of being involved in outdoor activities and learning. On the one hand it is a necessary component to keep my mental health on an even keel, while the physical acts often lead to bodily pain and uncontrollable fatigue and tiredness.

One way I’ve learned to manage this is to find the activities that cause the least pain. I go bird watching regularly and look for nature in the local landscape. If I’m away and walking is a part of the activity then I’ll have to prepare myself in the weeks leading up to the activities with rest, or gradual regular increased of physical activity. For some reason, walking is not a great outdoor activity for me and it brings on much more of the fatigue than canoeing. Something to do with the nervous system and my legs – don’t really know. Really, it is all in the planning, knowing my limits and having the confidence to say ‘no’… (which I’m terrible at).

Leslie: What have you learned about yourself from being in nature, as well as about nature itself? How do you try to pass on that reflective understanding to your students?

Lewis: I’ve learned that if we take nature (including the human, as we are nature too) as our starting point, then connecting different ways of knowing (whether traditional disciplines or through crafts of a kind, or anything in between) become a powerful and empowering set of tools to action. There is so much in my life that I have missed by having a narrowed perspective and perception of it, that realising no one area of knowledge, no one single way of doing something is ever going to really help us in resolving the human-made climate catastrophe we face. For instance, scientific inquiry gives us the lay of the land, but we need other insights and informed-actions to see a positive change in the data (and a positive change in real world, from every day harm to everday care). That’s what I mean, divisiveness and isolationist mentality isn’t going to get us anywhere. This connects to something I’ve learned about nature and bring into the classroom wherever I can.

Not so long ago, I started reading about the Wood Wide Web. This is the micro-fungal system that connects flora, especially tree life, together by almost unobservable mycorrhizae (a kind of mediating fungal root system). Through these connections, trees share their energy, communicate when one is under attack by a predator or invasive species. To anthropomorphise (softly here), there is a level of care in the community to preserve life, to keep life going, to keep it healthy. There is commitment to life, because life is all any living thing has. It is a commitment to a shared life, one of shared responsibility, one of give and take. All facilitated by the unassuming fungal network. I hope that educators of the present and the future will be able to see that their role is to facilitate an ecological care ethic which moves beyond the limitations of dissected knowledge and curriculum (political) interests and which supports our learners in become deeply educated, autonomous, free thinking and socio-ecologically responsible citizens. I want them to be wise mediators in our socio-ecological world.

Next week I interview printmaker Helen Peyton whose Smart Gallery social museum and art gallery has been long-listed for the Turner Prize.

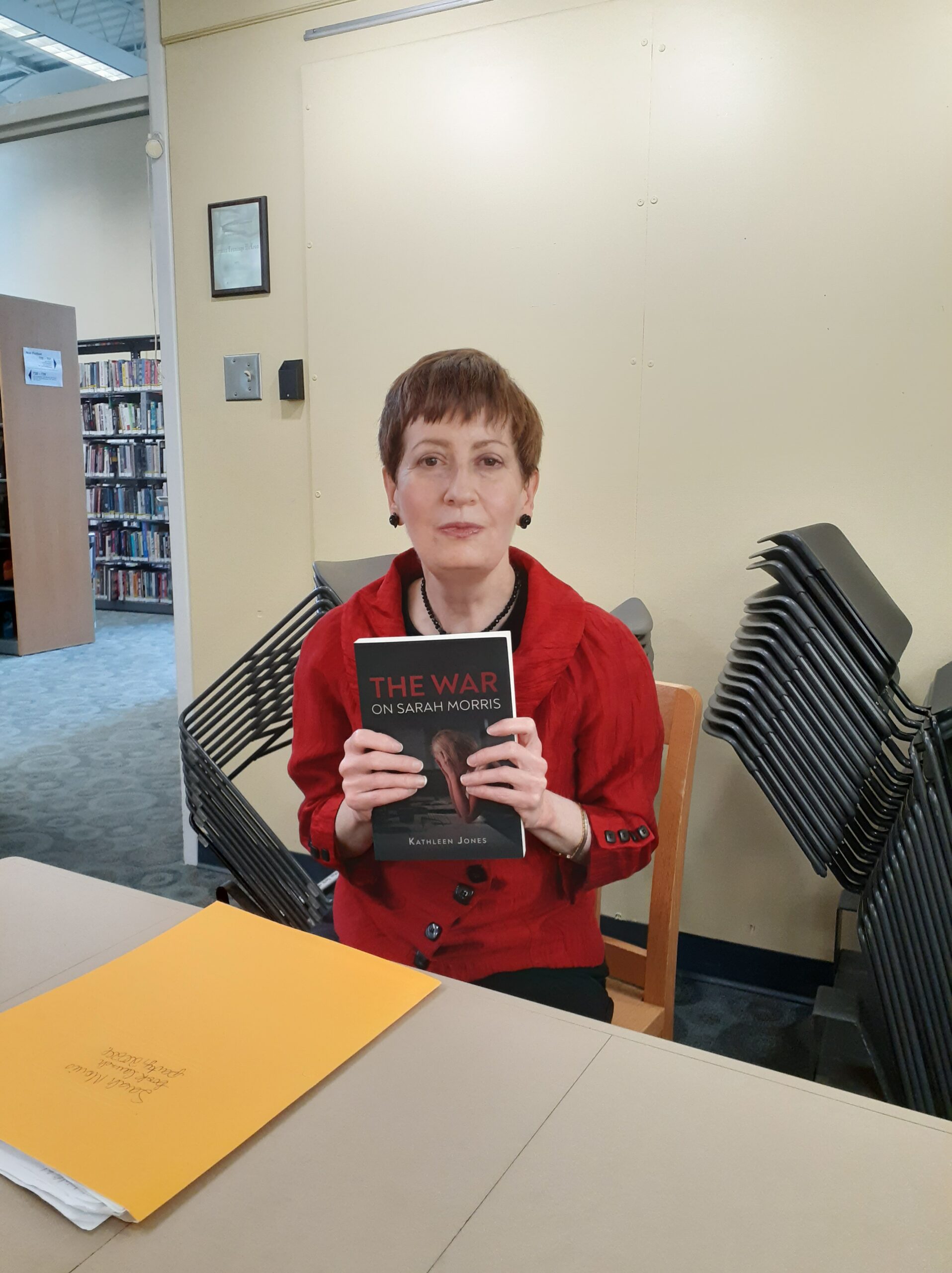

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

What a great interview. Love Lewis’s thinking!

Best wishes

Barbara

🙂 🙂 🙂