Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

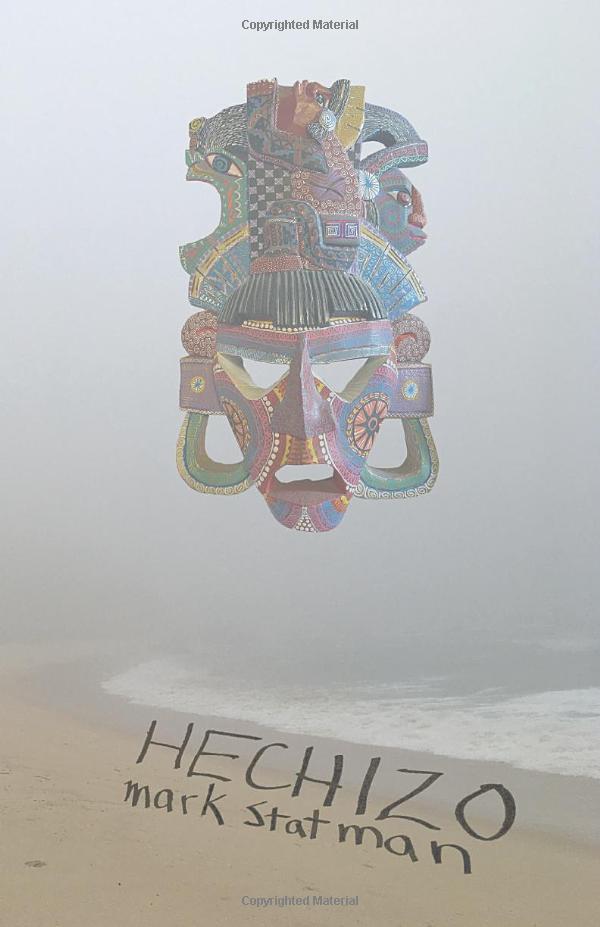

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Hechizo his 11th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, The New School, NY, and now lives in San Pedro Ixtlahuaca and Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico.

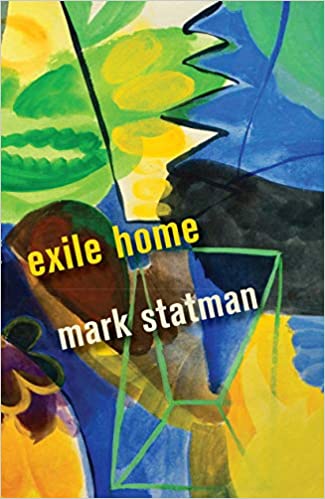

Leslie: You describe your new book of poems Hechizo as “… the yin to the yang of Exile Home… I see the two books as talking to each other, though they each very much stand alone.” Can you describe the original conception and process of writing Hechizo, and how it relates to your previous book of poems, please?

Mark: The poems of Exile/Home are ones I wrote in the time just before and in the three years or so after my wife, the painter and writer Katherine Koch, and I moved from Brooklyn, to the city and state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico in September 2016. It was an interesting and extraordinary time for us. We were leaving New York, the city where both of us had lived most of our lives, for another country, another culture, another world. Oaxaca wasn’t unfamiliar to us, but, despite previous stays there for weeks and months, we really only knew it as tourists. We were about to become permanent residents of the country.

Exile/Home talks about those changes, works through and with them. I think of the words exile and home as nouns and verbs. We left Brooklyn because the Brooklyn we loved no longer existed. We came to Oaxaca because it was a place both of us felt deeply, in all senses—physical, emotional, aesthetic, intellectual, spiritual. Exile/Home celebrates the changes, celebrates our old lives and our new lives. Though the book leads off with the long poem, “Green Side Up,” written for my father who died in March 2018 and never got to visit us, the book is primarily joyful, upbeat. Our exile took us from home, it brought us home. That kind of idea.

What Exile/Home doesn’t address at all, I think, are the other things that were happening in the world. The election of Donald Trump, growing authoritarianism throughout the world, environmental degradation, a pandemic. It doesn’t address my own demons, the emotional and spiritual ones, nor my alcoholism, with which I struggled for many years. Though I’m sober, sobriety doesn’t make one’s problems go away, it just helps make me better able to solve those problems.

Hechizo addresses these things. An hechizo is a spell—it can be a good one or a bad one. In the book here, it’s both, because my demons and the world’s demons will cast their spells but there are always the voices in one’s life, and one’s own voice as well, that can cast a spell to counter the destructive ones. But the struggle is ongoing.

Mexico is both the subject and object of the book. I am too. And so is the rest of the world, but what I wanted to address in the book was the other side, the things that Exile/Home left out. The two books go together.

I use the yin and yang analogy to show how the books complement each other. But they don’t complete each other and this analogy is going to fall apart with my next book, which is going to kind of bring it all together, a third set of voices to work with the voices in the other two books.

Leslie: Can you give a picture of the dangers and rewards of living in southern Mexico? How has that experience affected you as a mature writer?

Mark: It’s a funny question about the dangers. If by danger, one means crime and all that, I’m such a New Yorker, you can’t ever take that out of me, that to me a mugging or a theft seems kind of normal. My New York street sensibilities take me pretty far. I know there’s talk of drug cartels and stuff like that, but those are mainly in the north of the country. The pandemic did hit Oaxaca, whose primary industry is tourism, pretty hard. So there has been an increase in street crime. Our house in town, and other houses in the area, were broken into.

But I don’t feel unsafe here. I know how to live in cities, know what’s smart and what isn’t. When visitors talk about getting robbed at 4 am after a night of drinking and they’re walking in neighborhoods of which they are clueless, I think, well, this is terrible that this happened, I hate it, but it happens like this in every city in the world. Pay attention.

We have a rancho in the country, we even have a little cultural center there for readings, music performances, art exhibitions. I walk around at night all the time, not feeling in any danger at all. Does it help when I go on my walks, in centro or in the country that I have my 75 pound Labrador Retriever Apollo with me? Probably (laughing).

The rewards? Oh my. This is a stunning country and Oaxaca is a stunning state, with a history of art and poetry, music. A history of political activism. The indigenous voices here are quite strong. I’m spending so much time reading the Mexican poets, contemporary, modern, and going back to pre-Colombian. They are quite amazing and rarely talked about north of the border. I am studying a history which is rich and amazing and confounds all the things ever taught me in the northern schools.

But I’ve always loved Mexico, since the first time I came here in 1986. William Burroughs, a writer I rarely quote, notes in Naked Lunch how something falls off you when you cross the border from the United States to Mexico. That’s how I felt the first time I came here and continue to feel. Todos vuelven a la tierra—everyone returns and that’s how it’s been for me, as if returning. A funny thing for me is that my grandfather, my mother’s dad, loved Mexico and talked all the time about one day retiring here. And now it’s me with that life.

Now that I live here, life is measurably different. I’ve started the work to become a dual national, a Mexican and US citizen. I want to participate in that life. I don’t want to be seen as a guest, even an honored one, which is how I feel, but as a part of the body politic and a part of the process.

The effects on my writing have been intense. Hechizo and Exile/Home are books not just about Mexico and life here, but books that Mexico helped me write. By being away from the US poetry scene and the different winds that blow one this way and that, I’ve felt an incredible freedom. Not that I paid that much attention to the tempests and the fads, but I was conscious of them, I knew what was going on. Now I kind of don’t. I mean I know what’s going on, I read all the poets, my friends and my not friends, but the physical distance really does create an aesthetic distance. It’s just that I don’t worry much anymore. I just write. Grateful, very grateful, that there are amazing editors who publish me. An amazing shout out to Bill Lavender, first rate publisher and stunning poet. I’ve been fortunate to read his new augustine poems. They are wow.

But because of distance, the writing feels like it’s getting better. It feels like the kinds of things I dreamed I wanted to do, both formally and in terms of content, I’m doing. I’m not looking over my shoulder so nothing is gaining on me (pace Satchel Paige).

Leslie: Would you like to expand on how your personal demons enter and underpin Hechizo?

Mark: I’m not sure how much I can add that isn’t in the poems. I don’t think it’s much of an exaggeration that the politics of the world affects one.The political being personal. Environmental issues. A pandemic that changed everyday behavior. There was some beauty in the unreal way I could walk the streets of Oaxaca—the dog needed his walk!—and the eerie emptiness. Silence.

Personal demons. The death of my father brought out a lot. It was an important part of Exile/Home but in Hechizo I look more at the time after the death, the seasons of grief and loss, about the anger and struggles of his life and our lives. A whole section of the book has me facing my father, my father’s voice and voices, and his still-daily presence in my life. I think it resolves in love and presence, and I’m really glad I was able to write it.

In my new poems, not sure when that book will be ready, two years?—I once had a dream of a book of poems every two years! Now I’m happy to think my next book will be my twelfth. Should that make me happy? My dad’s father, my wonderful Grandpa Charlie, was a baker. We have a sincere relationship with bread in my family. So maybe I’ll be happier at a baker’s dozen.

My parents again figure a lot in the new work. My mom died this past September. The grief has overwhelmed me. More than my dad. But quieter. The tears flow a lot. At the age of 64, I’m suddenly and really an orphan. I have a great community here supporting me in that grief. In Spanish, the phrase is llevar luto. To carry or wear your grief. I certainly am. The grief presents me the chance to become hopeful. Hello Gloria Gaynor! I will survive.

Except in the notes at the end, I don’t specifically name my alcoholism, but anyone familiar with the disease will recognize the language and struggles. Alcohol hurt me emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. It gave the furies and lizards in my mind—the figures of both are prominent throughout the book—reign over me and my life. The person I became because of this abuse could be abusive, cruel, awful. I never wrote about my problem before because I didn’t feel free to do so. Another liberating quality of life in Mexico, feeling more able to reveal all of myself and not just the side of me I thought people might want to read about. Sobriety—not just physical, the drinking—but emotional and spiritual is something I’ve had to work on a lot. In Hechizo, I think one sees that struggle. And, again, there’s a lot in the book, along with struggle, of resolution and reconciliation, with my father, Mexico, with the world, myself. It’s all a little uneasy because still ongoing. The problems are all still there. But how do I face them, the furies and the lizards? One day at a time.

My very dear friend, the poet Joseph Lease, whose new poems are frighteningly brilliant and will be published by Chax , describes this all as “soul-making.” Hechizo is a book deeply focused on what that is, does, means.

Leslie: You mention a new note of foreboding in your writing. With climate change already impoverishing the poorest parts of the globe, are poets reduced to archiving a vanishing lifestyle? Or should they be sending up a howl of protest – or even putting aside their poetry to concentrate on collective action to avert catastrophe? How do you see yourself within this spectrum of behaviour?

Mark: This is a very powerful question and I really don’t think there’s a single answer. In fact, I think your questions contain all the answers. Yes, we are archivists. Yes, we protest. Yes, we should put aside our poetry and act. I think it was Brecht who wrote that it was hard to write about the trees when there’s someone behind them shooting at you. It’s hard to write merely about the loveliness of the trees when you’re seeing them being destroyed.

But it’s complicated too. I live in a country which depends on the oil industry for its economic survival. For which the nationalization of the oil industry here, ending US domination of that industry, is a point of national pride. We kicked the gringos out! Ironically Mexico needs its oil industry to economically afford alternative energy technology. To be able to make sure there is health care, education, jobs. There is a great sense of environmental urgency but there is also an urgent sense of providing basic needs—clean water, electricity, food— for the people of the country.

What should the poets do? Whatever we can. Whatever makes sense for each of us to do. I’m not much of an agenda poet. I was recently writing with the poet Jordan Davis and I noted that being of, as David Shapiro has put it, the “immortal left”, I don’t need somebody beating me over the head with their agenda shovel. And I feel no need in my poetry to beat anyone over the head with mine.

When Donald Trump was elected president, I turned to my son, Jesse “Cannonball” Statman, a brilliant singer/songwriter, and said, well, I guess the work is still there, it just got a little harder. And what’s that work? Myles Horton said it was combining love and social justice. And as a poet, I’d add, beauty. One of the things I want to do is put beauty in the world, more beauty, more and more. Beauty that challenges us, inspires us, makes us more human and, if that, I guess, more beautiful.

Three Poems from Hechizo.

Kiss of your agony Thou gatherest,

O Hand of Fire

gatherest—

-Hart Crane, The Tunnel

You need the shadow of a child

Like an avalanche

-David Shapiro, Spring

E io, che di mirare stava iteso,

vidi genti fangose in quel pantano,

ignude tutte, con sembiante offeso.

-Dante, Inferno, Canto VII

1.

last night

lateness sleepless

the Mexican landscape

the mountains mountains mountains

their great dark spreading

voice

in my

head of

my head

of too much

dust too much light and

sadness numbness

the world in

collision or collapse an

inability to even say

words my words any words of

disappoint confusion of

love reassurance

they my furies

2.

come whenever they

want to come in

daylight dawn midday

the pursuit which isn’t

pursuit because they

are always here pursuit as

present present as

pursuit

they with

talons sweet faces (illusion)

with poems song they

enter my body they

insect swarm they insect

invade they insect (sweetly)

here to help destroy

(the streets filled

with rainy season rivers

carrying leaves carrying

those voices which

will later fill the

rain which will

later fill the air

and the streets

grow more and

more like rivers I

don’t remember ever

over decades this

much rain this

many ghosts these

many broken words rivers)

they

to

read my mind here

invading

here

to

hold in

dystopian night

dreams nightmares

the new-found old

disease (their

sweet faces their

sweet songs songs

we sang marching

we memorized we down

by the river we who

would not be moved we

were always moved we

were always lost their

sweet nostalgia how to

tell these inhumans from

the others from the

angels the muses how

to know what was

howl what was body

a body ready ready

for sleep there is

where the beauty save

there is no beauty

there is no beauty there is the

4.

despair)

they live

off fear and love from

fear and fever how and

with you (me) your

(my) whole life in childhood

they seemed worse

fear even worse they are

than death to live through

that splitting the burning

trap suffocation something

even to the gods unbearable

and even to God how

it would be the end of

stories the end of

faith of hope the lifelines

erased life disappeared

the political disappeared the

children disappeared the

history of the world

the ghosts who

call them the memories

who call them

this is their power they

5.

like the ghosts at

the unmarked ruins the

buried all you see

a hill a tree piles of stones

or in the market where a

woman with herbs you

ask her a question she

says try these a

mix she makes she

shakes her head it’s

the best she can do it’s

all she can do she

(about to say something)

stops

because there

inside the dreams again

in the body what the body becomes

attacked and no alarm no

warning just the breaking open

of the earth the cracking open

a shell a thin young tree

a mighty old tree a body

like the earth the body falling

the trees falling falling buried

by everything becoming in

itself of itself the furies

there with their anger

their disease they are

born of night or blood drops to

water or air and earth

—anger rage revenge—

their bright eyes

dark glowing with

6.

the sun the

midday sun the

empty city you

think (I think)

ciudad de fantasmas

echo of steps no

voices there’s bird-

song there’s street dogs

in the park at

the newsstand no one

no one and no

newspaper no diario

to say the news

you already know the

furies swarm the

skies overhead they

settle in the trees

waiting

for what

for you to think

to feel so they

know without seeing

exactly where

you are

7.

the furies they

took our

heroes who

stood up who stood who

were beaten down

in peace in protest in

love they took

them we let them we

because we clueless

helpless ashamed we

had become

less than the

one who doesn’t know

to inquire we

fell

we so

afraid we had

become

of light of

daylight of

how much must

fall before

the truth

8.

is this

what they

are for

you are

no hero

poet make

your peace

with age

make

your peace

with death

death

the world

death

the loved

death

your own

make it

peace

as if

there was

a choice

as if

in saying

no

there’s

something else

9.

it’s knowledge they whisper

(soft) they know everything they

live with the truth the horrible

truth and the horrible

whispers and the horror that they

are come come to me to

places and bodies to mind and

hearts come to me where

they belong

why can’t you act like a father?

my most insane dream

in some time it had

airports and train

stations my brothers and

I were there someone

had died I don’t know

who we were al

meeting up to travel together

to mourn like a spy Russell

approached me in

disguise wearing a wig

big glasses a woman’s

hat he whispered I

heard you were looking

for a sinner then David

appeared his hair

long and he

wasn’t gray he said we

have to get moving

we were at an

airport maybe Laguardia

then Grand

Central Station

they posted the names of

the trains but ours

wasn’t there then

in the middle of it all

emerging like vapor like

steam as if from a locomotive

my father stood

I thought

smiling but it was a

frown he was angry angry

we had summoned

him but we hadn’t or

I hadn’t I was just

traveling I was on my

way to someplace else I

said I don’t even live

here anymore New York

the United States not

my country not

me from the

vapor steam and choking

cloud hell-fire my brother

Stuart came the

youngest one the one my

father so differently

loved Stuart had

his hands around my

father’s neck we tried to

stop him tried to

tear his hands away Stuart

was crying and screaming

a voice from duende from

darkness spirit blessed

hated Stuart’s hair was

alive around his head

serpents I thought

Stuart choking my father

suddenly then suddenly

he looked like

Jesse my son Jesse he

looked Jesse then Stuart

then Jesse then Stuart

again and again until a final

again it was Stuart just

Stuart rage coal eyes

coals and flames his face he

looked so much like my

father choking him choking

himself we couldn’t

break his hold we all

choking my father none

of us could stop and I

had to wake up it was more

than I could take Stuart’s

voice all that was left

except the look on his face

in the dream he’d learned

something he hadn’t

done a terrible

terrible wrong

hechizo

Lleva en el cuerpo la casa en ruinas.

Abre la tierra,

siembra algo que nazca no muerto.

-Marianna Stephania

1.

the image in itself the

image longing the I

love you and far away

I see your photo

I

cannot see

you

you

don’t res-

pond you

in your distance in your

difference you say I’ve

never thought of you you

say this isn’t how I

think you ask me

what God I believe in you

tell me some kind of

story your own story your

own God it isn’t my God your

story your words crush it’s

my chest

I take

these words

one word written over

another you

would try to you would say

¡ay!

what would that close

what

will you

open will you

turn to me

2.

I have an idea to

put

magic in the

fire

make

some-

thing

more

than fire this

will take time for it’s cue

from the gods

(there are still gods?

(there were are?

there is some-

thing in me

which shall

tire Torture and

Time and

breathe

magic magic curse

when I

expire

then the past

haunts the future the

the way the past haunts

me

3.

wind rose

rosa de los vientos

rose of the winds a

map of the winds

the compass where

does magic do it’s magic

the winds

have suddenly

come up do you

know how hard

it is to

conjure

lightning

have you

ever been

struck

wizard?

(who is the wizard

(who is the wizard

I

dumbstruck if I

look in your eyes I go

down I go

who knows

have you

learned I am

helpless?

4.

my mother says she is a witch

my Uncle Jackie was the wizard

I learned the hard way

do not mess with my family magic

5.

magic older

than Hecuba older

than that witch that priest that older

tree it’s a pochote tree it divides

earth from sky those older branches that

older river we are at the river we

are at the river older older and

older the fire

far-

gone the

world the ancient what is

the word I want to use to say before

there was a language before there

was breath before there was chaos and

order before there was the day or the

night you would walk around words

of careless inequality have

you heard the story of the wise

man he was an old wise man

he was our wisest wise man he

sold himself out to some magic

it wasn’t temptation it wasn’t

greed it wasn’t desire he thought

it is an art form it is an art form I

can become the

fallen in love I can

rescue the

fallen in love he was

fallen into the

wisdom of

no

and

6.

your word is an ancient word

your youth is an ancient world

your God is not mine but mine is

older mine will not refuse your God a

thing

7.

the wind comes

from all

directions the wind

fierce it is

fierce it is

going to blow the

house down it is

going to blow worlds

apart we have no

recourse but to

jump into the

dream not the

mirror the mind

wants mirror it

always wants mirror but

this shape across the

table this shape across

the dark night horizon makes

magic it possesses will

give you your sleep and

put you there s

o who

will wake up well you

asked the question you

decided to wonder who

it will be you or me you or

me

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

One Response

Love the poems. Love your Oaxaca backstory. Love Leslie Tate.