JANE BURN – POETRY AS HARD GRAFT, INSPIRATION, REACTION OR EXPERIMENT?

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

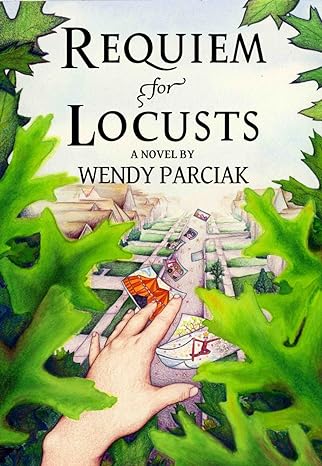

I interviewed author, musician, PhD ecologist and dog trainer Wendy Parciak, who talks about her adult literary novel Requiem for Locusts and why she switched to writing for middle-grade children. Wendy’s interview covers music, mental health, community ecology, writing methods and positive ways of training dogs. She says about her stories: “My goal is for them to come across as both unique and relatable.”

Leslie: Tell us about why you chose to be a writer, having been classically trained to concert level on the cello.

Wendy: In retrospect, I think I’ve always been a writer. I remember crafting a story in Montessori school titled My Trip to Alaska when I was four years old, which got ‘published’ by the local library. I can only hope it was placed in the fiction section, because I’d never been to Alaska! After that, I continued writing in school and in my journal, but once I discovered the cello at age nine, writing took a second seat to music.

It wasn’t until I injured my arm during my third year in music school that I learned I wasn’t going to be able to play the cello anymore and I’d need to find something else to do. Talk about devastating and mind-altering! After lots of self-examination and a very interesting session with a hypnotherapist, I switched to science (and lots and lots of non-fiction writing). Eventually, I had the fun realization that I might try fiction, since those have always been my favorite sorts of books to read. Now, of course, I wish I’d had that particular revelation a lot sooner!

Leslie: Why is your adult novel called Requiem for Locusts? How did it begin, grow and develop as a book?

Wendy: My first novel was written in an extremely organic way that I haven’t repeated with any of the others. I adore plotting, but for Requiem, I ‘pantsed’ the entire thing, starting with the title. Really. The title popped out of nowhere before anything else. Other than the general theme of the stigma of mental illness, I had very little idea of what I was going to write. After pondering that title, I decided it might be interesting to write about a dysfunctional neighborhood on the fictional Locust Street. As a song for the dead, ‘requiem’ in part refers to the extinct locust trees that used to grow where the houses were built. On a metaphorical level, ‘requiem’ refers to the tragedy that unfolds, largely due to misunderstandings of the actions of a mentally-ill girl who lives in the neighborhood. It makes sense on a musical level as well, since the mentally-ill character is obsessed with a particular piece of music and frequently chants the lyrics.

I started writing simply by exploring the point of views of seven neighbors on the street. One chapter and one character per day. It started as a fun character exploration, and the plot took off from there. But again, unlike all my other manuscripts, I had no idea where it was going or how it would end.

Leslie: Can you describe, in writing Requiem for Locusts, how you adapted key scenes and characters from your sister’s illness? What did you add; what did you miss out, and why?

Wendy: The most biographical character in the novel is the mentally-ill teen, modeled after my sister. I wanted the character to have the same illness as my sister, so I used very specific language for her that often came straight from my sister’s mouth. This included her fixation with royalty (princes, princesses, queens), her obsession over reciting song lyrics, her paranoia that someone was after her, her compulsive scribbling on books and pictures, and her behavior of wandering through the backyards and houses in the neighborhood, once with a plastic knife held in front of her for defense. At certain points in her treatment, my sister did all of these things.

It’s interesting to me that the one negative comment I got in a review of Requiem said something about how the mentally-ill character’s dialogue wasn’t ‘realistic’, when in fact it was the most real thing in the novel! Real life truly is stranger than fiction at times. I left out some of the most disturbing things, like the many times my sister pleaded with us to help her end her life because she couldn’t stand the hallucinations anymore. I also chose to end the novel with a feeling of hope, when in fact my sister’s real story did not end that way (she died in a nursing home at a relatively young age as a result of many health issues). But I will say that I personally found a sense of hope in my sister’s last month of life, in which she received so many letters from friends and family that she at last felt surrounded by a loving community. She took great pleasure in reading them aloud to us, and I like to think she died feeling like the princess she always wanted to be.

Leslie: Why do you love middle-grade fiction? In what particular ways does writing MG fiction differ from Requiem for Locusts?

Wendy: I adore MG fiction because I love kids of that age. They’re still discovering the world, often with a sense of wonder and curiosity, and they’ve got the brain power to start to make choices about how they want to live. They have plenty of struggles with family and friends, but they’re generally more focused on how everyone in their world can connect than are the angst-ridden teenagers of YA.

As a genre, I find writing MG a lot more difficult than writing Requiem because there are many gatekeepers (i.e., parents, librarians, and other educators) who are concerned with the content in MG books (note: I’m intentionally leaving politicians out of this list because I do not feel that they have any expertise in determining what makes a good book). You need to keep the word count within fairly short limits, watch your vocabulary so you’re not introducing too many big words, make sure those words are defined in the context of the story, keep the subject matter of heavy-duty topics toned down to an age-appropriate level, and write your kid characters with ‘kid’ voices rather than ones that sound adult. One aspect of MG that I still struggle with is keeping the stories relatively simple, with many fewer subplots than adult genres.

Leslie: What different sides of your personality come to the forefront in these very opposite genres?

Wendy: First, I must say that I don’t see these two genres necessarily as opposites. For instance, Requiem is literary fiction, and sections of my MG works are literary / poetic in tone as well. But I’ve found that I can express my own brand of humor much more effectively in MG than in adult fiction. This probably says something about me – that on some basic level I never grew up! I love channeling my inner child when I write MG, and I try to craft fun, adventurous stories despite their underlying serious topics (e.g., climate change, mental health).

Leslie: What have been the most important areas in ecology you’ve studied and experienced in the field? What have you learned about yourself and the world from these studies?

Wendy: In graduate school, I studied the consequences of seed dispersal by birds (i.e., birds that eat fruit and then poop out the seeds – but where? And what does this mean for the plant?). This involved lots of research in avian ecology and plant physiology, but by far the most interesting area of study to me was community ecology. Maybe this was because I had a terrific Community Ecology professor on my committee, but I know it’s also because this area has such global relevance right now.

Basically, community ecology is the study of interactions between organisms, and whether/how those interactions change in different situations. And of course one of the most dire ‘situations’ right now is the rapid climate change that the entire world is experiencing. It’s affecting the ranges, survivability, and competitiveness of species, resulting in tremendous changes in plant and animal communities.

I feel like I’ve been concerned about climate change far longer than it’s been a major part of the public consciousness. It’s terrific that people are becoming more aware of it now, and I hope this means we can do something about it before the mass extinctions our planet is experiencing become insurmountable (i.e., result in catastrophic collapses of plant and animal communities).

Leslie: As a dog agility trainer, how do you train a dog? What’s personal in your methods and what’s formula?

Wendy: I train dogs by what’s known as Positive Reinforcement Training. This means rewarding the dog when it offers the correct behavior rather than punishing it for offering the wrong one. You will hear no “ah-ah-ah’s” from me or my students! Having to give a dog a punishing admonition basically tells me that the dog doesn’t know what to do otherwise. Usually, this means you need to work on training alternative behaviors and add lots more reinforcement (rewards) for those desired behaviors. It also means fun! You can keep your tone lighthearted and have a great bonding experience with your dog rather than a frustrated screaming session. I remind my students of this a lot, and I always end the lessons before the dog wants to stop (a mentally tired dog is like a person trying to cram for a math final at midnight).

I also love using shaping as part of my training. As you can read in my Substack posts, this means marking new desirable behaviors as they happen rather than assigning commands to them right away. It keeps dogs from learning to tune out your commands because they’ve heard them before they were truly ready to offer them. As in writing craft, my dog training is a patchwork of the wonderful things I’ve learned from many dog trainers, both in workshops and in books and videos. But pretty much all of the more advanced training comes right back down to these two aspects: positive reinforcement and shaping.

Leslie: When you put pen to paper, do you experience it as a number of taught ‘tricks’ (as in your blog about training dogs), or as a search for individual voice? How do you edit yourself and write from the heart?

Wendy: Haha, I love likening dog tricks to writing craft! But of course it’s more than that. Learning the tricks merely gives us the foundation for writing a story, just the way it gives dogs a foundation for raising their criteria and expanding their knowledge to an entire agility course.

And just as every dog is different, so is every writer and every story. I can’t tell you how many times agility students (myself included) have said: “Oh, this will be so much easier with my next dog!”

And it never really is. Sure, you know a bit more about how the process will go, and the speed bumps to watch out for, but those bumps are in a different place every time. My current dog isn’t nearly as intelligent as one of my previous dogs (think ‘handsome jock’ vs. ‘genius’), so I have to adjust my training criteria with him for everything. He eventually gets there, but the process takes a lot longer and sometimes I have to approach it from an entirely different direction. I’ve found this to be true for stories, too. One of my MG manuscripts flowed out nearly effortlessly, but most have required careful thought.

Before I ever start to write, I outline the plot quite thoroughly because, contrary to what some might say, this frees me up to write from the heart later (of course, I’m certainly open to changing my outline as I go, and often do). I also do quite a bit of planning for each of the major characters. I write ‘prequel’ scenes that happen long before the story will take place, solely as an exercise in which I explore the voices and try to understand how those poor characters arrived in the confused state of mind the start of the story usually finds them (see Lisa Cron’s Story Genius). My goal is for them to come across as both unique and relatable.

Even with all this forethought, the first few chapters are often a challenge for me. I have to force myself to get those voices out on the page! But after that, they start to flow more easily – dialogue scenes in particular (advice to someone suffering from Writer’s Block: try writing a scene that’s almost pure dialogue). The hardest parts for me are sections in which characters need to move from here to there because it’s difficult to avoid repetition, and sections of world-building (especially tough in fantasy, where you need to find the balance between adding enough world for clarity but not so much that it slows the pace). If I’m feeling the flow, I’ll sometimes gloss over these harder things and come back to revise/add to them later. But I do consider myself to be a very editorial writer, almost to a fault. I spend a lot of time perfecting even my first draft–though the benefit is that I have much less to do in later revisions!

Next week I interview innovative Polish-Irish film-maker Anna Czarska

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed poet & artist Jane Burn who won the Michael Marks Environmental Poet of the Year 2023-24 with A Thousand Miles from the Sea.

I interviewed ex-broadcaster and poet Polly Oliver about oral and visual poetry, her compositional methods, and learning the Welsh language. Polly says, “I absolutely love

I interviewed Jo Howell who says about herself: “I’ve been a professional photographic artist since I left Uni in 2009. I am a cyanotype specialist.

Poet Tracey Rhys, writer of Teaching a Bird to Sing and winner of the Poetry Archive’s video competition reviews Ways To Be Equally Human. Tracey,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

2 responses

Thanks so much, Leslie! You are a wonderful interviewer.

Congrats