Part 2 MARK STATMAN: MEXICO AND THE POETRY OF GRIEF AND CELEBRATION

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

Two passages from Love’s Register inspired by famous artworks. Both are from Beth’s diary, written during her illness:

James saw it first in the garden. I remember his words, though at the time I didn’t really listen, not fully. It was out there and noted but not heard deeply or taken into my heart. There’s a voice inside where everything lives, and for me, although it was the truth, I’d not allowed it in. But for James it was real. He’d told me that the plants were out of step, that they were shooting and flowering before they were due. In the past, he’d said, he could plan for year-round interest choosing plants that came at different times, but now everything flowered at once. With that, he said, came swings in the weather: one day hot, the next day cold, with floods and gales and frosts then droughts. But mostly, he said, it was about lives that went under. I think when he said that I should have listened. But for me it was easier if I carried on as normal, just as it was. As far as I was concerned, the sun shone, the rain fell and we were happy in the garden. When it came to bio or climate, that was too much to think about and wasn’t going to happen. It was about as likely as children growing wings or falling from the sky.

But lives were being lost. James talked about disappearing birds, insects, animals and species going under. Everywhere there were casualties. The garden was on the danger list. Its body clock was broken.

So why did I deny? Mainly, I think, because the change was so slow. And when a big shift happened, I could see it as a blip, a one-off, something to be expected. Climate wasn’t on my list of things to watch out for. Up close it didn’t move. And if you turned your back it had gone when you looked again. Also, coming as it did in millimetre shifts and ppms, it was hard to measure. It was like walking in the dark. Everything was in flux, but unless you looked carefully you might not notice it.

But in any case, I turned away. There was something out of place, a glitch, a tear, a break in the surface. Someone was hurting, but I chose not to see it.

Climate is a mood, a condition. A tap drip, a knock at the door, a runaway ride. I feel it inside me as a shadow lengthening. It’s in the system. The bad stuff fattens on itself; it knows no boundaries. It’s my cancer, everywhere, all over, unlimited.

I listened to James. He’d shown where to look and now I could see it. I was with him as his lover in the garden. I’d found that place where the voice lives on.

And this is what I know now:

– Climate is our limit, our point of no return.

– It’s our freefall dive, our race to the bottom.

– Count the carbon; it’s our angel of death.

– The sun’s too close, the UV is inside us.

– Don’t look away from the burnout.

– It’s what we’ve done to ourselves.

– It’s the boy falling from the skies who no one sees.

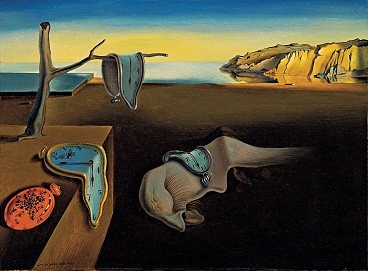

Recently I’ve been looking at Dali’s The Persistence of Memory. The soft watches describe how I feel: caught in the glare and melted, in a quiet way. The view out to sea is bright, while, in the foreground, the shadow of a mountain is filling up the picture. It’s a clean bare place with sharp lines and spread flesh. A Gethsemane. It reminds me of my first experience of death.

I was eight at the time, the year I wrote The Girl Who Began Again. I was alone in the back garden. I don’t know where my dad was, but I can still feel his absence. I was crouched down studying the path, seeing it as a jigsaw, an old one with bits missing. Parts of it didn’t fit. It was cracked and patched and smeared with concrete. Small, spiky weed-tufts showed around the cracks.

Taking a stick I began digging. I was poking at the side, exploring a crack, when a lump fell out. I remember sitting back in surprise. I can still feel it now, like an extraction. I was numb, trying to work things out. Had I done this, I wondered, and if I had, wasn’t it by accident? At the same time I knew the truth, and that made me jumpy. I had the stick in my hand and could see where the lump had landed, in the shadow of a bush. I hoped it wouldn’t get noticed.

I glanced back at the house then checked the hole. Just one peek, I told myself, and I’d be done. But what I saw scared me. I could make out a rough, cave-like space filled with roots. It seemed to be alive at the bottom as if it was bleeding.

I looked again. This time I was prepared, but it still made me shiver. The roots were full of dark, wriggly shapes. They were running all over in lines and knots, filling up the cavity. It seemed like they might boil over.

Then I realised they were ants, nesting. And in the middle, where they were busiest and blackest, they’d seized on something large. I watched in silence as they tore it apart. Body bits were held up, twirled in the air and cleared like rubbish. They were relentless. I began to turn away then realised suddenly what they’d got. The creature they were dismembering was a large, hollowed-out, silver-winged butterfly.

I was deeply shocked. How could they do that to something so beautiful? As if it was their prisoner. It was hard to understand. But also, by being the only witness, I’d got myself involved. And ants were ruthless, I knew that from school where a teacher had compared them to armies. I’d read about captive explorers being coated with honey and eaten by ants. But this was worse, their oddly-shaped, ritualistic movements were fiercely territorial. In them, for the first time, I glimpsed a different world.

For the rest of that day I could feel them with me. They were hiding in the loo, inside the plughole and underneath the bed. Like the ants in Dali they kept reappearing, on plates, through cracks, and dreamed in the mirror. At night I could feel them, tingling in my flesh. Even today, those ants are still with me. I can see them crawling on a clock in The Persistence of Memory.

I’ve read that Dali wanted to illustrate the theory of relativity. What I’d seen in action was the second law of thermodynamics. Leslie Tate

ABOUT THE BOOK:

Love’s Register tells the story of romantic love and climate change over four UK generations. Beginning with ‘climate children’ Joe, Mia and Cass and ending with Hereiti’s night sea journey across Oceania, the book’s voices take us through family conflicts in the 1920s, the pressures of the ‘free-love 60s’, open relationships in the feminist 80s/90s and a contemporary late-life love affair. Love’s Register is a family saga and a modern psychological novel that explores the way we live now.

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |