JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

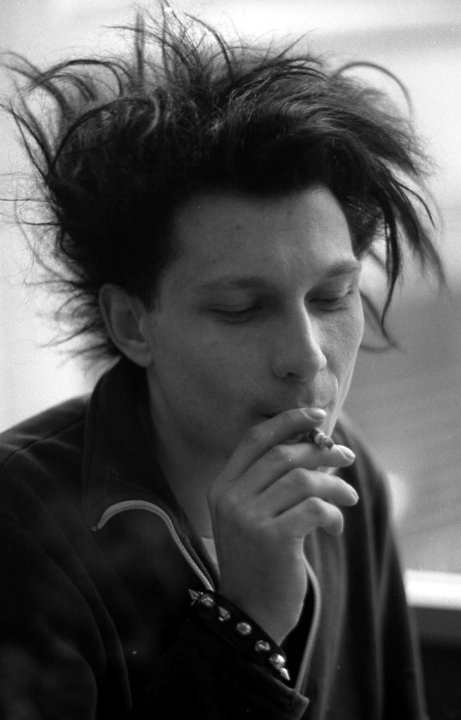

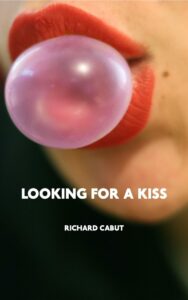

I interviewed prolific musician and novelist Richard Cabut who has published numerous fanzines and books, written for all the major musical magazines, and played bass guitar with post-punk band Brigandage. Richard’s new novel, Looking for a Kiss, is a post-punk, pop art, acid odyssey. His creative answers cover sex, music, creativity and cultural change. Enjoy!

Leslie: Your new book is called Looking for a Kiss. Tell us about the surface story and the deeper concerns. How would you describe the process of adapting your life to a story? What are the advantages and limitations of this approach?

Richard: Yes my new, and best book (so far!), is Looking for a Kiss. A couple of young punks, Robert and Marlene, are adrift in the post-punk 80s. They take acid by the side of the Regents Canal, in Camden, London. The book follows the couple’s progress as Robert reflects on the past and projects into the future, seeing, experiencing and, at the same time, meditating on breakup, breakdown, infidelity, desire, drugs, teenage perversity, clairvoyance, melancholy, madness, punk (what was once a way out has become a dead end, and the original sense of transcendence has become a quagmire), pop art, primal scenes and primal screams, the spectacle, time, toilet habits, faded chic, the self, personality crises, the endless search for cool/sprezzatura, memory, distance, passivity, vacancy, ambition, artistic success and the search for redemption. (It’s strong acid!)

Musician Paul T Kirk, said of the book: ‘A stunning, tour-de-force. Beautiful prose. Dragged me over coals but soothed me with balm.’

Do I adapt my life to a story?

Well, yes and no, but not really. Is the narrative an accurate portrayal of what happened in reality? Not entirely, no. Is it true? Yes, of course. I think we can say that truth doesn’t depend on facts. It depends on imagination and context. CS. Lewis said about truth: ‘For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition. It is, I confess, undeniable that such a view indirectly implies a kind of truth or rightness in the imagination itself.’ I’m with CS.

Anyway, the blending of the real and the invented is as old time; as old as you feel.

JM Coetzee says ‘We should distinguish two kinds of truth, the first truth to fact, the second something beyond that… we should take truth to fact for granted and concentrate on the more vexing question of a ‘higher’ truth… the best you can hope for is a story that will not be the truth but may have some truth value of a mixed kind – some historical truth, some poetic truth – a fiction of the truth.’ I’m with JM.

I love that idea of that poetic truth – one which grasps, like barbed wire, the essence of truth.

Writing is always edited and selected from a cache of imagination and memory as mentioned – sequenced and altered, sped up, slowed down, disconnected, reconnected in different ways. Public and private identities are configured and reconfigured – pushed and pulled – events compressed and distorted. In this way the ‘real’ story is disrupted and the new story becomes the unreal truth. Or vice versa.

Leslie: Your previous book Dark Entries is a satire about an aimless existence and an addiction to porn. How did you compose and revise it? Did you edit to avoid voyeurism/titillation for a certain kind of reader, or was this more about ‘telling it as it is’?

Richard: Dark Entries, as I write in the press release, is a pitiless and uncompromising dissection of the contemporary psyche. It is a savage and brutally honest peek at a modern lifestyle characterised by aimlessness, and self-abuse via reliance on extreme pornography and alcohol. Containing an atmosphere laden with sexual anxiety and frustration, the book is both a psycho pulp and an urban blues.

Ray, the main character, is actually based on someone close to me. He ended up in a sex addiction clinic. And then in hospital, treated for a mental condition

The point made in the book is that for people like Ray sexual hunger is not the result of lust, rather it’s a mania and an obsession. It’s a need, a compulsion. When you are suffering from sex addiction, the underlying objective is not to slake desire, but to allay or dissipate depression, feelings of deficiency or failure. It’s gaining fulfilment from outside origins to alleviate the internal, mental agony.

Of course, everyone is into porn these days – but I wanted to write about it the from the point of view that, where porn is concerned, the laws of supply and demand reign supreme– i.e. the reasoning of the marketplace and porn combine to underline the fact that there’s often nowhere left to go but to the laptop to amass dead empty orgasms – to adapt a situationist idea. To take that line a little bit further, I wanted to stress that the image has not only replaced reality it has, where sex is concerned, replaced fantasy, too. And that creates a sense of passive, narcissistic omnipotence. Which is a form of illness – which is where the book’s character comes in. He’s isolated, insulated and running on booze and porn.

Dark Entries is nothing to do with titillation or voyeurism, I wanted to create an unsettling portrait, acute and stingingly intimate – an extreme close-up that burns into the memory.

I feel privileged by the reaction the book has garnered in general. The art critic and author Neal Brown (Tracey Emin – Modern Arts Series) said: ‘An elegant and witty piece of gender dystopia horror writing, that also summons the gurgling death rattle laughs of addiction psychology. Really great. It is very nearly perfect. Beautifully crafted, droll, dry, and delicious.’ ‘Lou Reid (of the Glasgow band Lola and the Slacks) said, ‘What a stunning graphic sign of the fucking times!’ It makes it all worthwhile.

Leslie: You began writing by producing a punk fanzine called Kick. Can you describe how that started – the immediate stimulus and the people involved plus the bits of your earlier life that led you into creating it?

Richard: As a teen, I lived in small-town, working/lower-middle class suburbia – Dunstable, Bedfordshire. Thirty miles from the capital. There, kids left school and went on the track, the production line, at the local factory, Vauxhall Motors. If you got some qualifications you could join the civil service. Meanwhile, Trevor and Nancy had been going out with each other since Third Form and watched telly round each other’s houses every night, not saying a word. A preparation for marriage. I didn’t know what I wanted, but I knew I didn’t want any of that. Instead, I was in love with punk rock. I was in love with picking up momentum and hurling myself forward somewhere. Anywhere. I wanted to rip up the pieces to see where they landed. I was a suburban punk Everykid in pins and zips, with a splattering of Jackson Pollock and a little Seditionaries. In my bedroom there was some Aleister Crowley, a bit of Sartre, 48 Thrills (bought off Adrian at a Clash gig), Sandy Roberton’s White Stuff (from Compendium in Camden) and Sniffin’ Glue and Other Self Defence Habits (July ’77), of course. If, as the cliché has it, escape from the ghetto could only be achieved by means of sport or showbiz, then either learning three chords or scrawling a fanzine was the easiest way out of the suburbs for bored punk rockers. I was rubbish on guitar at the time, and so I started planning my first fanzine, which became Kick.

Leslie: Kick had some very special ideas about the punk movement. What were they and how did you illustrate/embody/bring to life your ideas?

Richard: Punk waxed waned but the early ‘80s were another punk spring. Punk at that time became a way of life for an increasingly large and motivated group of people. Moreover, folk were, to paraphrase Malcolm McLaren, creating an environment in which they could truthfully run wild. Instead of just listening to records in isolation and going to the odd gig, people were having life adventures – documented by fanzines, including Kick.

We were living in our own colourful movie (an early-ish Warhol flick some of us liked to think), which we were sure was incomparably richer, more spontaneous and far more magical than the depressing, collective black-and-white motionless picture that the conformists had to settle for. But we had a clear understanding of the here and now, and a desire to get out of it – rather than just get out of it.

Leslie: In your career as a journalist that followed, what were the learning experiences you took away from Kick? What are your most important journalistic pieces of writing – why them?

Richard: I suppose I’m best known at that time, in the early 80s, for the front cover Positive Punk piece for the NME. I wrote the article in January–February 1983. Really, it reiterated much of what I had previously written in Kick, and what other fanzines had reported, too, about the state of the punk scene in the early 80s. I liked the make-up-break-down, safe-when-dangerous, follow-the-heart-and-unconscious-mind, heaven-and-hell-and-kiss-and-tell bands like Bauhaus, Wasted Youth, Flesh for Lulu and Psychedelic Furs. Groups that promoted sensual style and re-action. And the Positive Punk article certainly garnered a reaction. Melody Maker wrote an amusing pastiche; The Face replied with its own piece complete with photos of all the key participants; there were myriad mentions in the fanzines; LWT’s Friday night arts and leisure series, South of Watford, devoted an episode to the ‘movement’.

In hindsight, the music wasn’t great but, as aforesaid, that wasn’t really the point. And then it turned into goth, with even worse music. In his book, No Future: Punk, Politics and British Youth Culture, 1976–1984 , Professor Matt Worley said: ‘Richard Cabut (Richard North – my pen name) was the first to outline the basis of what eventually became codified as “goth”.’ So, apologies for that!

Leslie: Are there seminal anecdotes you’d like to tell about the people you were involved with in the ‘80s? In human terms, what drove this huge creative outburst?

Richard: Michael Moorcock, the host of the South of Watford programme came to the house where I lived with friends, to conduct interviews. Seeing that we were all worse for wear after a late night at the Tribe Club, Michael kindly gave us some (extremely potent) speed to encourage the chat. It worked … perhaps all too well – Private Eye contacted me afterwards to ask whether it was true that the presenter had given drugs to his obviously over-refreshed interviewees. I denied everything.

Leslie: How did you go about editing Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night? As it developed, how did it surprise you? What did you learn from doing it?

Richard: Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night is an anthology published by Zer0 Books in 2017, with contributions from some of punk’s most important commentators and participants including Jon Savage, Penny Rimbaud, Judy Nylon, Jonh Ingham, Neal Brown, Dorothy Max Prior, Paul Gorman and Ted Polhemus. It was commissioned and put together mostly by myself – I also provided an introduction and wrote seven further chapters.

The book was widely reviewed. ‘Punk is Dead shows the transmission of culture as a kind of lucid group dreaming,’ Kris Kraus, The Times Literary Supplement, 9 January, 2018. ‘Richard Cabut… has chosen the theme of punk as a transformative force, a becoming,’ Dickon Edwards, The Wire No. 407, January, 2018. Author Deborah Levy chose Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night as one of her books of the year in the New Statesman, 17-23 November, 2017.

The book looks at some depth with an incisive cutting edge at, well, punk rock. It captures, I think, the subversive energy of the time. And it avoids academic jargon and style to comment and observe in sharp and entertaining ways, culturally, politically and philosophically.

What did I learn? Not to work with time-wasters any more.

Next week I interview Julie Noble about her successes in three writing competitions and her Radio 4 show ‘My Name is Julie’.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |