LISA DART – SURVIVAL POETRY AND THE VOICES OF EXPERIENCE

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed poet Natalie Scott about her prison writing uncovering forgotten histories, her use of dramatic monologue and poetry as therapy. Natalie has a PhD in Creative Writing, has two pamphlets and a full collection in print, and her poems have appeared in journals including Ambit, Agenda, English in Education, Aesthetica, Live Canon, Pennine Platform, Poetry Scotland and South Magazine.

Leslie: From what seeds did your poetry first grow? How did it develop?

Natalie: I always enjoyed reading and responding to poetry throughout school but my first proper ‘try’ at writing poetry was during my undergraduate English studies as part of an elective module in Creative Writing. I remember my tutor at the time – Carole Coates – being very encouraging of my work. I enjoyed having a go at using specific forms: triolet, haiku, villanelle etc. initially and then, as my confidence grew, I began to develop my own style and voice. She also recommended me to start submitting to poetry journals which I did. My first poem was published in Pennine Platform and it was a villanelle, so I was rather pleased with this! I decided that I not only liked writing poetry but I also liked studying the process, so I pursued a Masters in Creative Writing at Leeds University which I also enjoyed. Nature poet Terry Gifford was one of my tutors for this course – he encouraged me to experiment with forms on the page, finding a form that supports the subject matter. I remember how chuffed I was when he created an acetate (yes it was that long ago!) of one of my poems to show to the group. It was called ‘Dredging the River Chain’ and was shaped like a river decreasing in size.

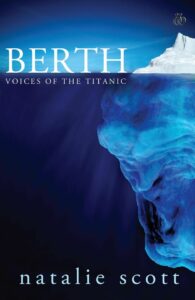

Leslie: Your first collection of poems Berth: Voices of the Titanic, used monologues to recreate the stories of the people involved in the event. Which dramatic monologues by other writers/performers have inspired you, and why them?

Leslie: Your first collection of poems Berth: Voices of the Titanic, used monologues to recreate the stories of the people involved in the event. Which dramatic monologues by other writers/performers have inspired you, and why them?

Natalie: There have been many writers of dramatic monologues who have inspired me but the most prominent poet is Edwin Morgan. I find his poetry both poignant and accessible. His voices are convincing, even for inanimate objects and animals. His poem ‘The Loch Ness Monster’s Song’ changed the way I viewed poetry as an art form when I first read it (and heard him perform it). To me it is a work of genius because of the way he uses patterns of language to create meaning. Many would dismiss it as nonsense verse but it makes so much sense to me. It sounds just like I imagine the monster to sound if s/he had been disturbed from slumber by an irritating tourist with a camera! I was also inspired by Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology which creates a narrative using the dramatic monologues of speakers who all represent people living in the same village. I love the way parts of a story can be slotted together with the fragments of different voices and perspectives. I’ve also been inspired by Carol Ann Duffy’s dramatic monologues. As shown by her poems like ‘Stealing’ or ‘Psychopath’ the dramatic monologue form is perfect for delving into the inner psyche of a character. Other inspirations are Robert Browning, Ai, Augusta Webster and Alan Bennett, but the list could go on.

Leslie: What have you learned from the process of writing dramatic monologues yourself?

Natalie: I’ve learned about it being a ‘double-form’ with both the voice of the character and that of the poet being present. I’ve also explored polyphony – many voices – and how to use them in longer works. I personally find it quite a liberating experience to write from the perspective of a character as it enables me to step outside of myself for a moment and experience the world from someone else’s point of view –a bit like an actor playing a role. It is also a great form for encouraging empathy with other human beings. You have to pour yourself into their life to imagine what they see, hear, feel, taste and smell. In my first pamphlet Brushed (Mudfog, 2009) I created dramatic monologues from the point of view of figures in famous works of art. My poem ‘Victorine or Naked Woman in Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur L’herbe’ allows the ‘object’ of the painting, the muse, to show the scene as she experiences it: naked while the male figures are fully clothed. As you might imagine, she has a lot to say!

Leslie: How do you search for a character’s ‘voice’?

Natalie: Most of the time I like to choose a character that may not have had much of a chance to speak yet, as a real or imagined speaker. I do this to allow someone who might be considered to be on the margins to have a voice. However I am also conscious when making a selection that I can connect with a potential reader/audience, so I try and choose characters/objects that are identifiable with most people on some level. I particularly like voicing inanimate objects – I did this for the ‘Anchor’ and ‘Second Class Plate’ in my collection Berth Voices of the Titanic (Bradshaw Books, 2012) as it enabled a familiar story to be narrated from an unusual angle. I also voiced ‘Felix Baumgartner’s Spacesuit’ to explore a well-known news story (of the man who did a sky dive from space) from the point of view of the less celebrated but wholly essential ‘object’: his spacesuit. Influenced by Edwin Morgan’s Stobhill, a series of dramatic monologues which tell the story of a woman who had an abortion from multiple points of view, I like to present different versions of stories. This worked well for Berth as I was able to juxtapose the voices of two female passengers boarding the ship, one first class and one third class, to show the varied but also similar experiences of both women.

Leslie: Can you describe the aims of your next collection, and the preparation that will go into it? How do you carry out your historical research?

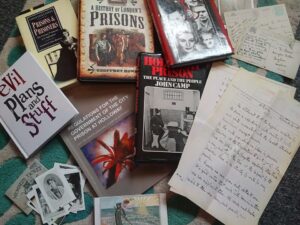

Natalie: My next collection Rare Birds – Voices of Holloway Prison aims to retell the story of Holloway Prison’s beginnings and development between 1852 and 1955 in a distinctive and engaging way. My poems will adopt a range of interesting first-person perspectives, including the voices of actual prisoners, staff and other influential people involved in the prison’s history to create a polyphonic retelling. In addition to the dramatic monologue form, I will be using a wide variety of other poetic forms in the collection such as found and list poems which will use actual documented material sourced from the prison archives to shed light on the topic from a new angle. Thus the collection will be a creative retelling rather than an historical report thus intends to make an original contribution to existing works on Holloway Prison. I was awarded Arts Council funding to research and write the collection, and have completed the preliminary research and reading required. I also have an outline for the collection in terms of the individuals I would like to voice – these include some of the Suffragette prisoners who spent time in Holloway during the early 1900s. I have a vision of how it will tie in with women’s history but also want to include the period in which Holloway was a mixed prison to tell its story faithfully. Once complete I will aim to publish in book form and collaborate with other artists to create a theatrical production.

Leslie: If you use or adapt other texts into your poems, how do you make sure the end result uses ‘the best words in the best order’?

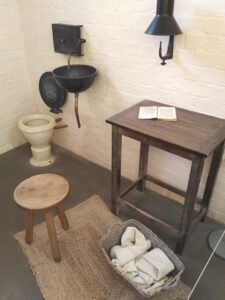

Natalie: I have to think carefully about how the form and structure will support the subject matter. For example, I’ve been working on a found poem made from a list of the items some of the first prisoners would have had at their disposal in Holloway. A book called The Criminal Prisons of London by Mayhew and Binny (1862) has been helpful for this as it clearly outlines the specifics of each cell. I let the triadic pattern of the shelves inform the structure of the poem itself, using a three-stanza list form to convey the items kept on the three-tiered shelf. Some of these items might be considered ‘everyday’ but become unusual in their juxtaposition: Bible, gruel-pot… but others are more unexpectedly luxurious: salt-cellar, two combs. I thought it important to represent the items accurately but wanted them to say more than the literal, so with a bit of careful placement within the lines of the poem they hopefully take on a new, and perhaps more symbolic, meaning:

Natalie: I have to think carefully about how the form and structure will support the subject matter. For example, I’ve been working on a found poem made from a list of the items some of the first prisoners would have had at their disposal in Holloway. A book called The Criminal Prisons of London by Mayhew and Binny (1862) has been helpful for this as it clearly outlines the specifics of each cell. I let the triadic pattern of the shelves inform the structure of the poem itself, using a three-stanza list form to convey the items kept on the three-tiered shelf. Some of these items might be considered ‘everyday’ but become unusual in their juxtaposition: Bible, gruel-pot… but others are more unexpectedly luxurious: salt-cellar, two combs. I thought it important to represent the items accurately but wanted them to say more than the literal, so with a bit of careful placement within the lines of the poem they hopefully take on a new, and perhaps more symbolic, meaning:

blankets: pair, pillow, rug, sheets: pair,

hammock, mattress: horse-hair

spoon: wooden, plate, gruel tin,

salt-cellar: wooden

combs: two, hymn-book, prayer-book,

brush, floor-scrubber, Bible

Leslie: You’re involved in recreating characters and their stories. Why do you use poetry rather than prose to do that?

Natalie: After years of practice in many genres, I feel that poetry (especially dramatic poetry) is my main art form now. I find that it is the best form for me to most effectively articulate what I want to say. For me, poetry is as much a science as it is an art: I’m in love with form and structure as much as I am the subject-matter. They have to share the same breath. I love it when my own voice melds with that of a character I have created. The way that poetry can focus a reader’s attention on a pinprick moment in time always astonishes me in poems I have read and admired. There is both a conciseness and intensity about poetry which suits me as a writer and a human being. It is an outfit that seems to fit me best.

Leslie: You seem to want to break down the barriers between the arts and, in particular, between text and performance. What or who has led you in that direction? is the art of ‘pure’ poetry on the page an anachronism today?

Natalie:I don’t think that there is necessarily a ‘pure form’ – poetry from any era will have qualities that are informed by earlier forms, styles and subject-matter. I also think that any poem has the potential to be ‘performed’ through dramatic reading or presentation if the voice has something interesting to say. However, I believe that the way a poem is written on the page is important. I spend ages drafting my poems to get them right on the page, but the way they are on the page informs the way they should be read aloud. I believe that poetry should be as much listened to as it is read on the page. The way we write a poem helps a reader to voice it and thus enables others to hear it too. Using a mixed mode of presentation excites me as a poet because I have an interest in many art forms. I like painting, photography, sculpture, dance and film almost as much as poetry, so find it an exciting prospect to bring these media together as a way to complement each other. I think that it’s also a way of introducing new audiences to poetry – the audiences that, having emerged from a traditional education system, think poetry is all about sitting in a classroom analysing a poem to death.

Leslie: Could you tell us a little about your use of poetry as therapy, please?

Natalie: A couple of years ago I was inspired by an article in MsLexia magazine which was about poetry therapy. At the time I had no idea such a practice existed but it sounded interesting, so I did some investigation into the field. I found out that poetry therapy has been a recognised practice in the US for at least the last forty years, and involves a three-way process of reading a poem, responding to it verbally and then creating a written piece. The poem is selected by its emotionally engaging qualities and universality, so that people can have a ‘feeling response’ to it and might be encouraged to engage personally with the subject-matter. I am now in the process of completing a practice-based qualification offered by the International Federation for Biblio/Poetry Therapy and am being supervised by Victoria Field, one of the only registered poetry therapists in Europe. Last year I established my own initiative Pen Power which offers a range of group sessions for people who wish to maintain their levels of mental fitness through expressive writing. I facilitate these sessions in the Teesside area but am hoping to widen the reach over the coming months.

Leslie: Finally, how has living in Middlesbrough affected your poetry?

Natalie: So far it has helped me to get my poetry out there much more than anywhere else I have lived (I’ve also lived in Lancaster, Hexham and Wakefield but am originally from Durham!) This may be due to the stage I am at with my poetry right now – I generally feel more confident with what I am writing and enough people have said positive things about my work to keep me moving forward with it. Contrary to what many people might believe, there is a thriving poetry scene in the Tees Valley. There are some pioneers I must personally thank for this: poets such as pa morbid who organises the Black Light Engine Room – a monthly poetry gathering which includes four guest speakers and an open mic. Although many of the people attending are northerners, the guest speakers come from further afield, so there’s a real variety in the poetry each month. I’ve always felt valued and welcome at this event. I was also warmly encouraged by Kirsten Luckins (Apples and Snakes) to join the Tees Women Poets, a collective which has attracted some of the best female poets in the region to participate in poetry events organised by the group.

Next week, in THE ROMANY SPIRIT AND THE GIFT OF ILLNESS, Raine Geoghegan talks about her Romany heritage, and how her writing and stage work have been affected by M.E. and Fibromyalgia.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

3 responses

This is a fascinating post, Leslie. I am very interested in Natalie’s book of poetry about the Titanic. The use of poetry as a therapy is something quite new to me.

Yes, there are many uses of poetry. Thanks, Robbie. 🙂 🙂 🙂

Thanks for your interest in my work, Robbie. I’m glad you liked the post! If you wish to discuss anything further please feel free to contact me via either of my websites.