SARAH ROSS-THOMPSON AND THE ART OF COLLAGRAPHED PRINTS

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

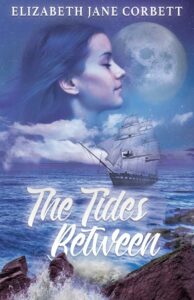

I invited Elizabeth Jane Corbett, who won the Bristol Short Story Prize and was shortlisted for the Allan Marshall Short Story Award, to write about how she discovered Welsh Mythology. Elizabeth lives in Australia, where she teaches Welsh, is an author and librarian, and her debut novel The Tides Between is published by Odyssey Books.

Elizabeth writes:

I am not an expert on Welsh stories. I didn’t even know they existed until my forty first year – not the fighting, red and white dragons, not the Lady of the Lake, or Taliesin, or the Mabinogion, or any of the strange tales of changelings and fairy borrowings. I’m not sure how unusual my ignorance is for the average Briton. But to me it is akin to an aboriginal Australian growing up without any knowledge of the Dreamtime. A travesty. I think that’s why the stories hijacked my Aussie immigration novel. Why, Rhys, one of my viewpoint characters ended up a storyteller.

It is no accident that most of the world’s belief systems are based on narrative. Whether religious or not, stories lie at the heart of our human experience. Novels, films, oral folk tales, news stories, or specifically religious writings, stories help us make sense of our lives. Rhys tells two full length Welsh fairy tales over the course of the five-month voyage to Port Phillip, as well as a political tale. His wife, Siȃn tells another fairy tale and, Bridie, my fifteen-year-old protagonist tells one of her dead father’s stories. In her thoughts, Bridie refers to a number of others. This was risky. I could have alienated my readers. However, the feedback I’m getting is that the fairy tales felt integral to the story.

They weren’t initially. In my early drafts, I simply made them a point of connection between Rhys and Bridie. I fully expected readers to skip over them. But as the relationship between my grieving girl and Welsh storyteller grew and, as I received feedback from various readers, it was clear that, to be included in full, the stories needed to work harder. To this end, I set myself three goals. Each story must be:

In terms of the first goal, this meant a great deal of re-writing. The stories as I read them (initially in English) were mere skeletons of what must once have been a richer form. For of course, these tales were originally oral tales, told to explain a landform, or a sickly child, or to give hope to an oppressed people, that were embellished with each re-telling. My aim was for the reader to become so caught up in each story that they forgot they were reading a novel – as the listeners on my migrant ship would have forgotten themselves momentarily.

Achieving the second goal took a bit more effort. I didn’t want to change the integrity of the traditional tales. However, I reasoned the oral storyteller would have told stories that resonated personally. Therefore, his re-telling would be subconsciously influenced by the issues with which he grappled. Here is a section from Rhys’s version of the legend of Taliesin. I have glossed over some elements and emphasised others. I wonder if you can get an inkling of Rhys’s issues? In fact, the story does not only touch on Rhys’s struggles, it also speaks to Siȃn and Bridie’s journeys. Though, I’m not going to tell you how. You’ll have to buy the novel. :)

‘Now Elffin the Unfortunate was a plain, honest man,’ Rhys continued, ‘and therein lay his problem. For his father, Gwyddno Longshanks, had lost his prime lands through neglect and expected Elffin to make good his misfortune. To this end, Elffin was sent to the court of King Maelgwn Gwynedd. Alas, poor Elffin was neither a warrior nor a hunter. He was certainly not cut out to be a courtier. His prime quality was an honesty that did not allow him to speak with a double tongue. He served Maelgwn without distinction, married a woman without wealth or position, and settled happily on his father’s remaining estates.’ ‘“Fool!”’ His father shouted. ‘“Wasting every opportunity. How can we expect to prosper, if you will not exert yourself?”’ ‘“I am content with my lot, Father, and to earn my bread in peace.”’ ‘“Peace! Contentment! What about when our enemies invade?”’ ‘“Our prime enemy has been neglect. And you have allowed it to prosper.”’ ‘Now Elffin was a kindly soul and, despite his honest tongue, it grieved him to disappoint his father. He tended his hives, herds and flocks always hoping to win a measure of approval. But Gwyddno Longshanks was a hard, exacting man and, no matter how plump Elffin’s cattle, nor how fine his fleeces, nor how clear and golden his honey, he took no pride in his son’s achievements. ‘“Tonight is May Eve,” Gwyddno announced. “The door to the otherworld will swing open. If you cannot make a fortune in my salmon weir tonight, I will wash my hands of you.”’ ‘Now the salmon weir was Gwyddno’s pride and joy. All day, Elffin toiled in preparation for the catch, re-setting the weir poles and ensuring the wattle fences were in good working order. But his efforts were doomed from the outset. For that night, a vengeful witch cast her ill-born child into the sea. When Elffin and his father rode down to inspect the weir the following morning, they found nothing but a bulging leather bag, hanging from its poles.’ ‘“You have broken the luck of the weir!” Gwyddno sneered, turning away in disgust. “Was a son ever so unfortunate?”’ ‘Elffin’s eyes stung as he pulled the leather bag from the water. Why must it always be like this? Could not fortune once favour him? To his surprise, the bag squirmed in his hands. Opening it, he found a baby nestled in its folds, a baby boy so beautiful Elffin’s heart filled with love for him. Imagine his wonder and surprise when the child began to prophecy.’ ‘Elffin of steadfast heart.’ ‘Be not dismayed. ‘For I bring blessing.’ A shiver worked its way up Rhys’ spine, as Siân took on the otherworldly voice of the child. She may not have been cast upon the sea by a vengeful witch but she’d been abandoned at birth and raised by a wise woman and there were rumours, terrible rumours that her birth was cursed. ‘Small and weak, as I am ‘Washed up by foaming waves, ‘In your day of trouble, ‘I will prosper you, ‘More than three hundred salmon.’ ‘“Diawl!” Gwyddno lurched backwards, making the sign of the cross for protection. “The child is bewitched! Throw it in the water!”’ ‘Elffin turned, ready to fling the bag back into the weir. But as he looked down into the child’s innocent face, his breath caught. Such beauty, his eyes so deep, soulful. A poet’s eyes. How could they possibly abandon him? ‘“He may not be what you expected father. As I am not what you expected. But I will not destroy him. Look, how he smiles! His brow so radiant! I shall call him Taliesin.”’ ‘Misty May morning, ‘Elffin’s misfortune, ‘Take this tale as your own, ‘Wisdom and wonder, ‘Wealth for the taking, ‘Find yourself in his story.’ ‘As the child grew, it became apparent that he and Elffin were as unalike as earthenware and crystal. For although Taliesin possessed an honest heart, he showed no great talent for husbandry. He spun tale of flower maidens, bubbling cauldrons and otherworldly swine, named the stars from north to south, and wrote verse that none could ever rival. But although Elffin listened to these fantasies with wonder and pride, he doubted Taliesin would ever aid him in his day of trouble, let alone, prosper him more than three hundred salmon.

The novel is prefaced by a segment from the ballad of Tamlane, a story which acts as a metaphor for Bridie’s journey. Likewise, Rhys and Siȃn’s finds echoes in the Lady of Llyn y Fan Fach. The metaphoric element of the stories is not obtrusive. People have read The Tides Between without noticing them the first time round. However, people are telling me they get more out of the stories on a second reading.

The stories played one extra role in the novel. One I hadn’t intended. For in them, I see something of my own journey. For example, when one of my characters says, ‘Painful, it is, when the words that once brought comfort lose their voice. It’s not the stories that are at fault. Or that we were foolish to believe. Only that we must learn to see with different eyes.,’ I am expressing something of my own, evolving relationship with a group of ancient writings commonly known as the Bible. Similarly, when another character reflects: ‘There were no easy answers only love and people who were complex.’ I am speaking out of my own growth in understanding – an understanding that life is not black and white, that some of the easy answers I once accepted are no longer satisfying. However, it is in a very early scene that the effect of the novel is most telling.

The Tides Between opens with Bridie walking from the emigrant depot to the Deptford watergate, a forbidden notebook bumping in a canvas bag at her side. With a brief last-minute intervention from Rhys, she manages to get the notebook onto the ship. But her mother is suspicious and Bridie spends an anxious afternoon hovering about their berth. Come evening, she finds a chance to escape, forgetting Rhys has also sought the peace and quiet of the main deck. In Bridie’s desperation, I something of my own despair at having being denied my ancestral stories.

The Tides Between opens with Bridie walking from the emigrant depot to the Deptford watergate, a forbidden notebook bumping in a canvas bag at her side. With a brief last-minute intervention from Rhys, she manages to get the notebook onto the ship. But her mother is suspicious and Bridie spends an anxious afternoon hovering about their berth. Come evening, she finds a chance to escape, forgetting Rhys has also sought the peace and quiet of the main deck. In Bridie’s desperation, I something of my own despair at having being denied my ancestral stories.

Bridie gazed out over the blackened river. Mills turned slowly on the Isle of Dogs opposite. Small piers and granaries broke the smooth, dark, silhouette line of its shore. The sight strange and foreign, as if they had already crossed an ocean. Somewhere, beyond the docks, mudflats and the City of London, lay the cobbled streets of Covent Garden. The streets her dad had walked, their lodging house within calling distance of the theatres. The musical, magical cellar where she’d etched his fairy tales onto the crisp new pages of her notebook and run her finger over his final message and still felt his presence, long after he was gone. She didn’t know how long she stood there. Only that the light thickened and the night air fell like a chill shawl on her shoulders. Turning back towards the hatchway, she heard an eerie drawn out sound from beyond the deckhouse. She halted, nerves feathering her spine. A long slow note pierced the evening. The fiddle? Ah! Rhys. He was playing an air, an-oh-so familiar air, from the Beggars’ Opera. One her dad had played so many times—towards the end with tears coursing his cheeks. She turned slowly toward the sound. In the shadow of the deckhouse she stopped, her breath coming hard and fast. Every piece of music held a story, her dad told her—a thread that attached itself to the heart. She’d become attuned to those threads, growing up to the strains of Mozart’s Magic Flute, and Purcell’s music for The Tempest, hearing tales of fairy queens, Arabian nights and midsummer dreams—and this was a sad song, quite apart from Peachum and his cronies in the Beggars’ Opera. A long haunting melody that spoke of a sadness and longing. Head bent, eyes closed, Rhys’ lashes made a smudge against the night-white of his cheeks. It might have been the melody, or simply her fear of discovery. Maybe the memories of her dad. But she saw a struggle in the lines of his body that went beyond the music. Something in the long, measured stroke of his bow, that put her in mind of a sapling bent hard by the wind. She found herself dissolving at the sight. She didn’t know how long she stood there, fist jammed in her mouth, trying not to sob aloud. Forever, it seemed, until the music drew to a gentle close. She didn’t clap, though his performance surely deserved it. She turned quietly to leave. ‘It’s called Ar Hyd y Nos,’ his soft voice followed. ‘All through the Night, you might say in English.’ Bridie stopped, hugging her arms to her chest. ‘Welsh, it was, long before Gay made use of it in his opera. A love song, recorded by Mr Jones in his Relicks of the Welsh Bards. I’ve heard it many a time, though, I’m not convinced of the lyrics. It speaks sorrow, to me, quite apart from the romance. Death, perhaps, or ambition gone wrong? A secret? What do you say, Bridie Stewart? Am I being fanciful on the eve of a long and difficult journey?’ He knew. How did he know she’d been listening? ‘I’ll not force you to speak, bach. Only seeking your thoughts, as you’re haunting the deck along with me.’ Silence. He waited. She stepped forward, pulse thrumming. ‘I can’t stay out long, Mr Bevan, because of Ma. But I liked your playing and I agree about the melody. It speaks sorrow to me too.’ ‘Indeed!’ ‘My dad was a theatre musician. So, I’ve heard that tune loads of times. I’ve always fancied it a lament—for a fairy who had died.’ She stopped, aware of how foolish that must sound. For some reason, she didn’t want to appear foolish before this soft voiced young man with truth-seeing eyes. ‘I suppose, if there are Welsh words written in a book, I might be wrong. About the fairies, I mean. Not about the sorrow.’ He laughed. ‘You mustn’t apologise, Bridie Stewart. Where I come from, beauty is often attributed to the fairies.’ Was he in earnest? She peeped up at him through her lowered lashes. Found his smile, a pair of warm, dark eyes, an eyebrow raised in query. But how to explain? About her dad’s love of fairy tales? How, in the early days, before he got sick, her world had been filled with wonder and stories, how they lived still in her memories.’ ‘We played this game, in the cellar of our lodging house in Covent Garden, with spangles and feathers and a magic stone. My dad made it up to keep me amused while he was practising. If I played quietly, without once interrupting, the fairies would leave a gift for me. Nothing fancy, only baubles and trinkets. Back then, I thought even his music came from the fairies.’ For a while, he didn’t speak. Turning, he laid violin and bow in the case at his feet. ‘Is that what you’re hiding, Bridie Stewart? A gift from the fairies?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Something forbidden, you couldn’t bear to leave behind?’ ‘Forbidden, yes, but not bad, Mr Bevan. At least, I’m not doing any harm. It’s a notebook, filled with fairy tales. My dad gave it to me before he died.’ ‘And now you are leaving the home of your childhood, with its cellar and magic fairy memories, and you wish to carry his presence to the far side of the world?’ She nodded, a lump forming in her throat. He knew. How did he know? How did this young man understand what Alf and Ma couldn’t? ‘Ma wants me to forget him, Mr Bevan, and his stories. But I won’t, ever. Even if I have to keep my notebook hidden in Port Phillip.’

Elizabeth writes articles for the Historical Novel Review. You can learn more about her and read her blogs at her website here. You can buy The Tides Between here.

Next week in WHEN CIRCUS MEETS THEATRE, I interview Lucy Van Hove, critic and participant in theatre-circus and advocate for this innovative art form.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed artist Sarah Ross-Thompson whose exceptional Collagraphed prints use fabrics, lichen, porridge and string to create images of the dramatic Scottish Highlands where she

Part 2 of my interview with Mark Statman looks closely at Mark’s Latin American poetic influences, his life in Mexico and ends with an extract

I interviewed international poet and translator Mark Statman about Volverse/Volver, his 14th published collection. Mark, who has won national arts awards, is Emeritus Professor of Literary

I interviewed Lisa Dart, finalist in the Grolier, Aesthetica and Troubadour Poetry Prizes and author of The Linguistics of Light (poems, Salt, 2008), Fathom (prose

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

6 responses

oh, wow. I had tears in my eyes reading the excerpt where Bridie listens to Rhys then tells him about the faery tales. I must read this book, although it will make me cry as I already see threads from my own life story. It will be a wonderful tale.

Yes, Elizabeth Jane Corbett is a really talented writer. Enjoy! L x

Please do let me know what you think!

This was a fascinating look into a writer’s journey–both the inner journey and the writing journey. It’s amazing how fairy tales written and told so long ago can inform our lives today. The circularity of the process is astonishing. Thanks for the post.

Thanks, Amy. If you’re interested, there’s another post about Elizabeth and her writing on my website, where I interviewed her https://leslietate.com/2017/12/4322/#more-4322

Thanks Amy! ?