JULIA LEE BARCLAY-MORTON – YOGA, WATER AND REWRITING AUTISM

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

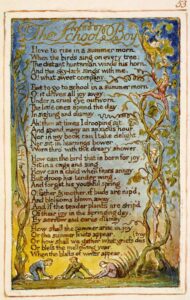

‘Without contraries is no progression’ – William Blake.

![Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection 69152[1]](https://leslietate.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/691521-204x300.jpg)

The first big trip was the annual Christmas drive from London to the NE. It took twelve hours through hail and snow with my dad white-knuckling the car around corners like Ahab in a storm. I sat in the back being good. At the end of that drive there was Christmas with family and lights and parties where everyone loved me. It was the kind of journey into darkness where the battle against the elements had a bright-and-shiny ending.

When we returned home it was less edgy, more everyday and ploddy. There were real ups and downs, with threats and scares and school bullies around the corner, but there were also chances to talk with the girls, or to play ‘chain tag’ in the yard. It wasn’t idyllic, but I didn’t get ‘bashed up’ and I had friends on my street. And when we set out in summer on the trip up north I knew I’d be the centre of attention, digging and playing all-hours on the beach.

When I was nine we relocated from London to Sheffield. This was a very different story. London was suburban, Sheffield was tough. We rented near the city centre and I attended a junior school at the top of the hill. The building was black and bunker-like, and the pavement outside was covered with spit marks. It was as if there was a war going on. Once a month, the top class would form up on one side of the playground and all the rest would gather opposite. When a boy shouted “Go!” they all charged into the middle and beat each other up. Secondary school in Sheffield was worse. One teacher would sit next to a pupil at a desk and jab him repeatedly with a ruler, another pulled boys’ hair; I remember the headmaster demanding mightily that we all memorised a chapter of Exodus. He was our RE teacher but always came late. On the day of our test, when he required someone to repeat the chapter, I stood up. I’d spent hours learning it by heart but I was shaking so much I couldn’t speak.

Outside the classroom, the boys took things further. There were fights and insults and youths calling themselves ‘the sex club’ who grabbed each other’s crotch and exposed themselves in corners. Later, at home I was ‘educated’ about girls by my cyclist mates. I was told with a grin that what you did was stick it – or that – up her knickers. It seemed so horrible that I decided not to have anything to do with it, ever.

After Sheffield we moved again, this time to a Northumberland village on the edge of the coalfield. The bullying there was relentless. I didn’t have friends, but now I was able to read poetry and walk out in the countryside on my own.

After Sheffield we moved again, this time to a Northumberland village on the edge of the coalfield. The bullying there was relentless. I didn’t have friends, but now I was able to read poetry and walk out in the countryside on my own.

Looked at as a narrative, from childhood onward I’d climbed the story arc reached the top but now, in youth, I’d slipped back to the bottom. Lower than that, because the songs about war and fights in alleyways plus the sexual jokes about milk bottles and keyholes had broken my confidence. I was no good at sport, blushed too often and ducked out of fights. In the game of snakes and ladders I’d slipped off the board. And that was when the inner life, which had always been there, became my chosen journey. On that journey I was able to draw on those painful early experiences to describe my hero learning about ‘what the boys called ‘it‘ in my novel Purple.

I shall trace the way of imagination in my next blog, but I still wonder how that other journey, with its fists and abuse, didn’t stop me altogether. Maybe the answer’s that unless you have problems you don’t ask questions.

I don’t believe that life is simply about moving on. When we travel, the movement is both outward and inward. We may travel in hope or run in fear. And the arc may be backwards or forwards, or both. Everything’s in motion: your mind, your eye, the earth itself. The question is what you make of it.

ABOUT LESLIE TATE’S BOOKS:

I interviewed writer Julia Lee Barclay-Morton about her experience of autism. Julia began as an experimental dramatist in New York, moving to the UK to

I interviewed Gillean McDougall from Glasgow, who edited the collaborative projects Honest Error (on Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald) and Writing the

I interviewed French writer Delphine de Vigan, whose book, No et moi, won the prestigious Prix des libraires. Other books of hers have won a clutch

I interviewed Joanne Limburg whose poetry collection Feminismo was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; another collection, Paraphernalia, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Joanne

I interviewed Katherine Magnoli about The Adventures of KatGirl, her book about a wheelchair heroine, and Katherine’s journey from low self-esteem into authorial/radio success and

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |